In October 1993, filmmaker Stewart Raffill had two weeks to think of something to do with an eight-foot animatronic dinosaur offered to him by an associate. He naturally decided to put Paul Walker’s brain inside it.

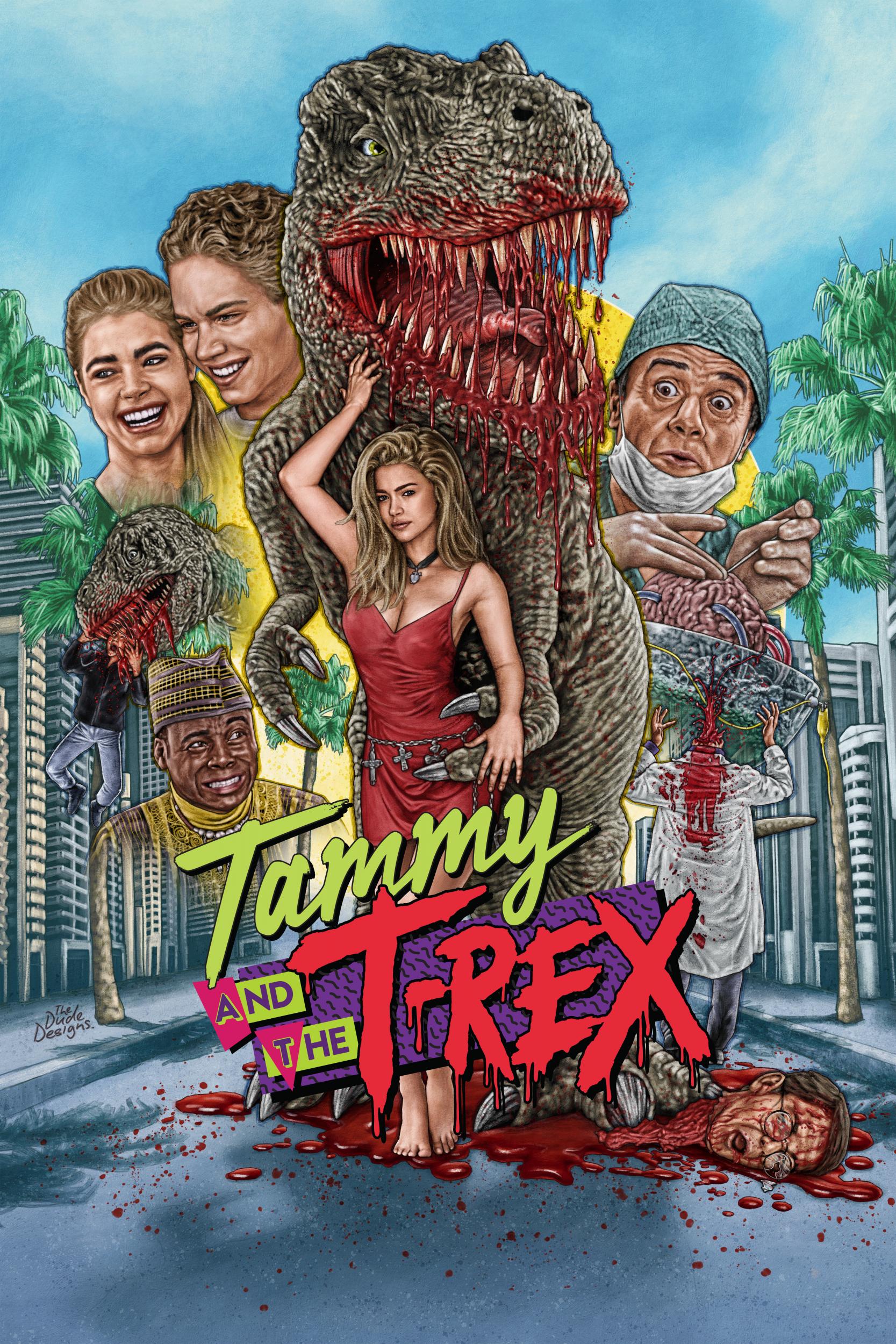

His resulting movie, a bizarre sci-fi comedy titled Tammy and the T-Rex, has since become a cult classic. For years it was traded in underground film circles on low-grade VHS, where fans were awed by its dirty jokes, Nineties kitsch and scenes of a pre-fame Denise Richards weepily cradling her dinosaur boyfriend in a barn. In 2019, however, it has been exhumed in pristine quality for a cinematic re-release, complete with all the graphic gore that was shot but left on the cutting room floor more than 25 years ago.

A surreal blend of harebrained silliness, exploitation cinema and Stephen King’s Pet Sematary, Tammy and the T-Rex stars Richards and Walker as a giggly high-school couple named Michael and Tammy, whose burning love is interrupted by Tammy’s psychotic biker ex, Billy. After being badly beaten by Billy and his biker buddies and then set upon by a lion, Michael is left in a coma. But thanks to an evil German scientist named Dr Wachenstein and his uber-sexualised female assistant Helga, Michael’s brain is surgically removed and placed inside of a robotic dinosaur – for reasons only vaguely explained.

Michael, his consciousness now inhabiting the T-Rex of the title, manages to flee his captors and reunite with Tammy, who is saddened but supportive of her boyfriend’s new body. Working with Tammy’s best friend, an outrageous gay teen presumably modelled on RuPaul, the pair roam the streets of LA to find a more suitable body for Michael’s transplanted brain.

Raffill, the director behind such B-movie classics as Mannequin 2: On the Move and the McDonalds-sponsored ET knock-off Mac and Me, is fully aware that Tammy and the T-Rex is deranged. “You had to think, ‘What can I do with a half-decent bloody dinosaur?’ and so you just had to have fun with it,” he tells The Independent. “It was done as a campy movie, because you couldn’t take it seriously.”

The animatronic dinosaur used in the film came into Raffill’s life, he told Bristol Bad Film Club, in the way these kinds of movies usually do: as “part of some tax evasion scheme”. A German film distributor based in South America, with whom Raffill would go on to experience creative and financial conflicts, appeared on his doorstep with an intriguing offer: a million dollars to shoot a movie in three weeks’ time that would involve the dinosaur he mysteriously had in his possession.

“I said, ‘Oh great, is it trained?’, Raffill remembers. The distributor explained that it was fully animatronic, with a moveable head, arms and feet. Raffill was intrigued. “I said, ‘What’s the story?’ and he replied, ‘Well, I wouldn’t be calling you if I had a f***ing story!’” Working with the late first assistant director and actor Gary Brockette, Raffill threw together a passable script in a week.

Production on Tammy and the T-Rex began in earnest two weeks later, with shooting locations chosen due to their proximity to Raffill’s own home to save time. Filming also coincided with a rash of Los Angeles wildfires, with firefighters attempting to shut production down to prevent possible injury. But Raffill didn’t have enough of a budget to delay filming, so he ignored them. “We ended up filming with the fire blazing in the background,” he explains, “and you can see it when Denise is riding the dinosaur – you see the haze of it behind her.”

Twenty-two-year-old Richards, who would become a star three years later via films such as Starship Troopers (1997), The World Is Not Enough (1999) and the erotic thriller Wild Things (1998), was plucked out of obscurity to play Tammy. Raffill recalls how uncomfortable she was during a scene in which she was asked to perform a sexy dance for Michael’s disembodied brain.

“She was from the Midwest and she was extremely, you know, puritanical when she came [to Hollywood],” he says. “And I said, ‘Well, at the end I want you to take your clothes off and do a dance for him, and [she said] ‘Oh, I can’t do that!’ So I took her to Victoria’s Secret or somewhere like that to get an outfit for her [that she was comfortable with], and then she was kind of corny as a dancer. She was not somebody who could get into being sexy just yet. She evolved into that later.”

Today, Raffill says that Richards “comes off the best” in the film, but also lavishes praise on The Fast and the Furious star Walker, who died in a car crash in 2013. “He was always full of joy, he was like a soul that was happy,” he remembers. “He was never a great ‘actor’ per se, and he would always tell you that. He always put himself down somewhat with his acting. But this [movie], he cottoned onto easily. He wasn’t in the best place with his acting yet, but he could play this and get into it and be totally convincing. So he was a joy to work with.”

The presence of Walker and Richards lends Tammy and the T-Rex an air of genuine sweetness, the pair giving the project their all despite its overt ludicrousness. The film that surrounds them is similarly delightful, its tone sandwiched between the the try-hard awfulness of the Sharknado series and the sincere and accidental sins of Tommy Wiseau’s The Room. The latter quality is where most of the laughs can be found: in the crop-top Walker wears in its early stages, the howlingly inappropriate jokes at the expense of his comatose character, or a scene in which a T-Rex uses a payphone.

But, in its most traditionally seen form, it’s also oddly disjointed, with abrupt cuts and what feels like missing scenes – an effect that adds to its cheap-and-cheerful charm, but also hints at at troubled post-production. In truth, it was. When Raffill presented his financier with a cut of Tammy and the T-Rex, which was filled with blood, murdered teenagers and disembowelling, he was appalled: “He said, ‘No! I wanted a Disney movie!’” Raffill remembers. “So he recut it into a piece of nonsense.”

The PG-13 cut of Tammy and the T-Rex, which Raffill immediately washed his hands of, was released on VHS at Christmas in 1994 as a family-friendly comedy. It was also a half-formed thing sapped of its violence, yet with its sexual undercurrents and dirty gags very much intact. The film got lost in the glut of family movies flooding the home-video market in the mid-Nineties, before being unearthed in recent years by the Midnight Movie crowd. Those film fans, hungry for cinematic curios best watched in communal environments where throwing popcorn at the screen is loudly encouraged, have turned it into a camp classic. Like The Room, Troll 2 or Birdemic: Shock and Terror, Tammy and the T-Rex has appropriately taken a seat at the “Best-Worst Movies Ever Made” table.

The film’s original cut proved a runaway smash at Video Vortex, a monthly event held by the Alamo Drafthouse cinema chain, which aims to screen “ultra-bizarre movies from the fringes of the universe”. But rumours of an extended, gore-filled cut inspired Joe Rubin to try and track it down. As co-founder of Vinegar Syndrome, a distribution company specialising in restoring and re-releasing rare cult films, he was the perfect person to bring Tammy back to life. It’s now about to receive the high-profile release it never had back in 1994, with a restored version of the film’s “Gore Cut” arriving on DVD and Blu-Ray this month, on the heels of worldwide film festival screenings.

“I actually very easily found the lost footage on YouTube,” Rubin recalls. “Because the uncut film had once been broadcast on Italian TV, which someone had videotaped and then cut together with the censored American video version, and had then uploaded it. I watched it and enjoyed it and went searching for the rights.

The journey from there proved unusually tricky. Rubin was sent back and forth between Raffill’s wife and frequent collaborator Diane and a number of possible leads, few of which came to anything. Eventually, he was put in touch with the man who currently owned the rights to the film, and “after a couple of months of haggling”, was able to get it unearthed. Raffill’s original cut still existed in its entirety, so minimal technical restoration was needed.

“I think that this is the perfect time and place for its rediscovery,” Rubin explains, “in large part because the Nineties are now in vogue as a kind of ironic, retro period. It was no doubt a tough sell at the time [it was made], because people would have thumbed their noses at it, or never even considered watching it. But now years later it has a level of ‘Look at this weird curio’. But it’s also easy to just appreciate it as a purely entertaining exploitation movie.”

For Rubin, the film reminded him of classic exploitation cinema of the Seventies and Eighties, where the limitations of a tiny budget and a rushed production schedule allowed for casual surreality, weird innovation and outré ambition.

“Even though it’s very much entrenched in the culture of the early Nineties, in the way people talk and dress and act, its type of weird is closer to what you’d expect in a Seventies movie,” he says. “Those movies weren’t about spending six months in pre-production, and doing weeks of rehearsals. The creativity came less from the planning and more from how people were forced to improvise, whether literally or figuratively while they were making the film.

“I think that’s one of the reasons the film works, because it doesn’t feel like someone spent months of their life figuring out what it was going to be. It’s like, ‘OK, we have these elements, how can we throw them together and make something that is moderately coherent?’”

Raffill is shocked that the film has earned a fanbase so long after it was made. “It’s come out of left field, but it is fun that it’s come back around,” he says. “Everyone loves when something like that happens. Sometimes these things capture people and they get into it, these campy things.”

As for the animatronic dinosaur of the title, its whereabouts today remain a mystery, even to Raffill. “We just had it for two weeks exactly,” he recalls. “And then they drove off with it.”

Tammy and the T-Rex screens at London’s Soho Horror Festival on 17 November, and will be released as a limited edition Blu-ray/DVD and 4k UHD/Blu-ray combo via Vinegar Syndrome on 29 November.