Anyone who has experienced the blistering pain associated with biting into a fresh apple pastry or taking a swig of hot coffee can attest to the importance of blowing on your food or drink before introducing it to your mouth.

It turns out that black holes may perform the cosmic equivalent of this routine, "blowing" on blistering hot matter before they gobble it down.

This supermassive black hole-food cooling process was discovered by astronomers using NASA's Chandra X-ray telescope and the Very Large Telescope (VLT) to observe some of the universe's most massive black holes at the hearts of seven galaxy clusters.

The team found that when jets launched from supermassive black holes strike hot gas between galaxies in galaxy clusters, called the "intracluster medium (ICM)," they carve out large cavities.

This allows complex filamentary structures to form from both hot ionized gas and cooler gas. This cooler gas then falls back toward the center of the galactic cluster, feeding the supermassive black hole and triggering further outbursts.

The team's research was published on Monday (Jan. 27) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Hungry black holes whip up a meal

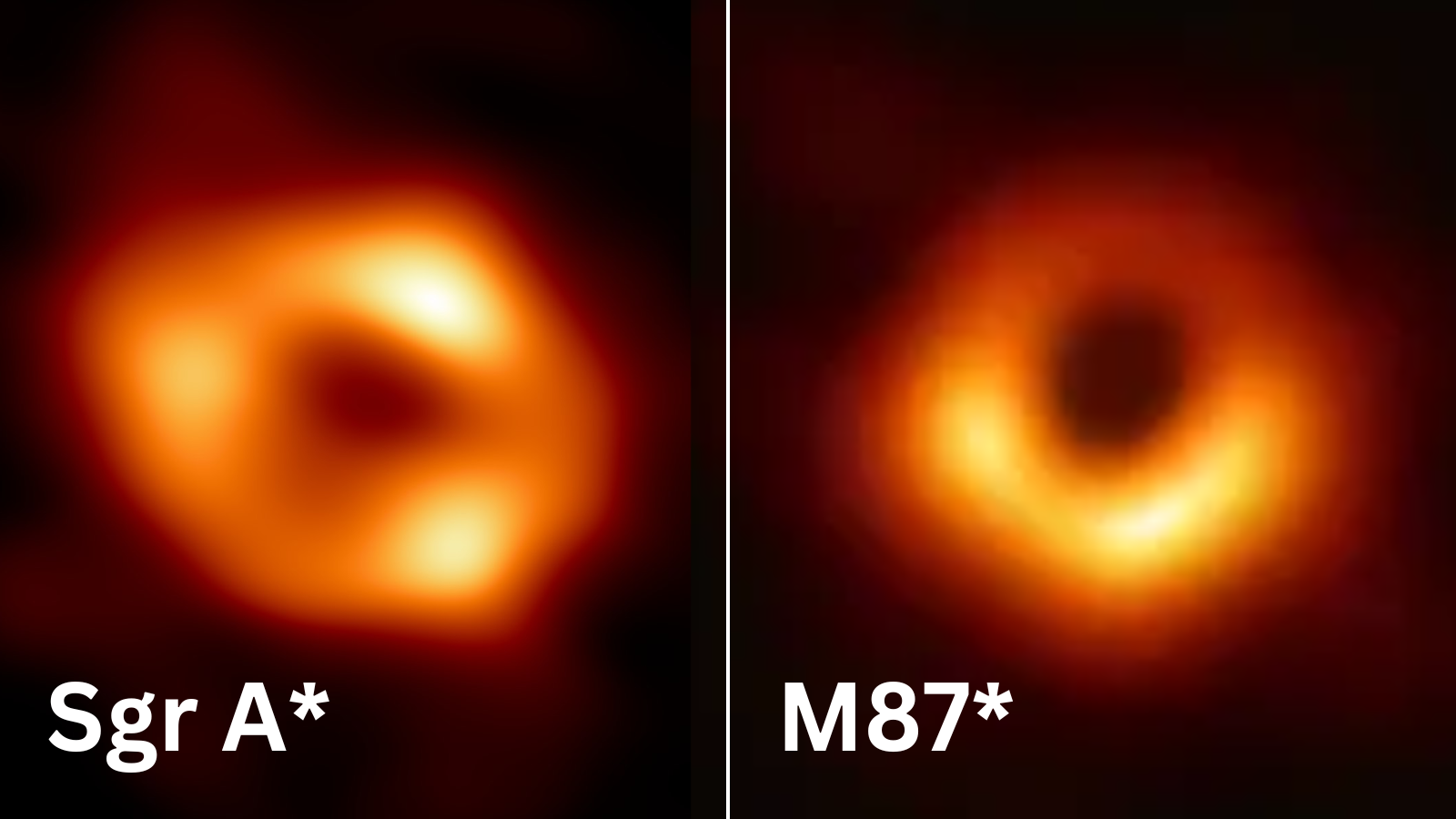

Supermassive black holes are cosmic titans that sit at the hearts of all large galaxies. In some cases, these black holes, with masses millions or even billions of times that of the sun, are quiet like Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*).

Other times, these cosmic titans are subject to violent outbursts, launching powerful twin jets of material that stretch well above and below the planes of their host galaxies and traveling at near-light speeds.

An example of this is the supermassive black hole at the heart of the galaxy Messier 87 (M87), the first black hole imaged by humanity, noted for its energetic eruptions.

Sgr A* has a mass 4.3 million times that of the sun whereas M87* has a mass of 6.5 billion times that of the sun, but that mass disparity isn't the reason the latter is much more violent than the former.

The key difference is the fact that the supermassive black hole of M87 is voraciously feeding on matter, while the Milky Way's central black hole exists on a diet so sparse it is comparable to a human eating a single grain of rice every million years.

Black holes feed like this when they are surrounded by a wealth of gas and dust that forms a flattened rotating cloud called an accretion disk. Matter that isn't fed to the central black hole can be channeled to its poles by powerful magnetic fields, from where it is blasted out as astrophysical jets. The region around a feeding black hole is called an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN), and the jets of these black holes are referred to as "AGN feedback."

The team behind this research didn't look at supermassive black holes like those at the hearts of the Milky Way and M87 but instead at examples that can be up to tens of billions of solar masses, located at the centers of galaxy clusters.

Black holes like their food cool

The supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxy clusters also blast out jets that are powered by their feeding on surrounding gas and dust.

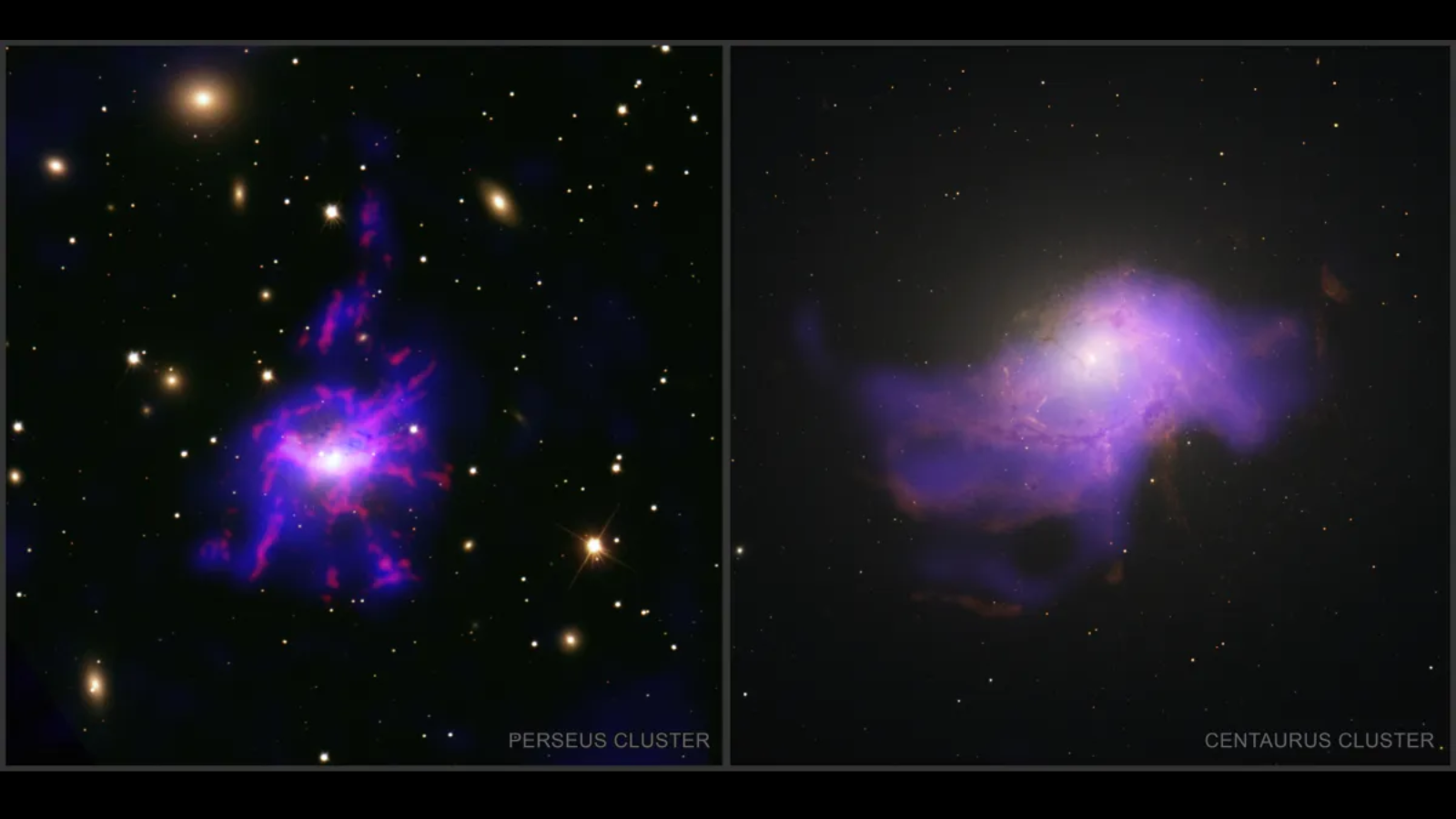

The image below shows the Perseus Cluster or Abell 426, one of the largest structures in the cosmos located around 240 million light-years away. It is composed of thousands of galaxies that are enveloped in a vast cloud of hot gas.

The next image (below) shows the slightly less massive galactic cluster known as the Centaurus Cluster (A3526), which is home to hundreds of galaxies and is located around 170 million light-years away.

Both images were produced using Chandra and VLT data.

The blue regions represent X-rays emitted by super hot gas by the former. The red tendrils weaving through this gas represent filaments of cooler gas seen in optical light by the VLT.

This supports a theory suggesting that outbursts launched by black holes can cause the hot gas around them to cool and form relatively fine filaments of still-warm gas.

The warm gas falls toward the hearts of these clusters, joining accretion disks and thus feeding the supermassive black hole located there. This process also powers further jets, ironically bringing in more warm gas and restocking the black hole's larder.

This model of supermassive black hole feeding suggests there should be a connection between how bright both the hot gas filaments and warm gas tendrils should be.

This relationship would mean the cooler gas should also be brighter in regions where the hot gas is seen. This represents the first hard evidence that such a connection exists, and that gives vital support to this theory. The connection the team found connecting these gas filaments is akin to that seen in the gaseous tails of so-called "jellyfish galaxies."

These are galaxies in which gas has been dragged away as the galaxies travel through surrounding clouds of dense gas and dust, forming long tails.

The team's findings may have significance beyond black hole feeding mechanisms, too. That's because cool filaments of gas are thought to supply the building blocks of new stars.

That means the relationship uncovered could be integral to galaxy growth as well as supermassive black hole growth.

These results were possible thanks to an innovative technique involving Chandra data that allows hot filaments to be distinguished from other structures. This includes the large cavities in vast hot gas clouds also sculpted by black hole jets.