The price of gold has reached almost US$1,760 (£1,438) per troy ounce in recent days. This is causing euphoria among long-term gold investors, who have seen the price rise from US$1,050 per ounce since mid-December 2015. Will it rise even more?

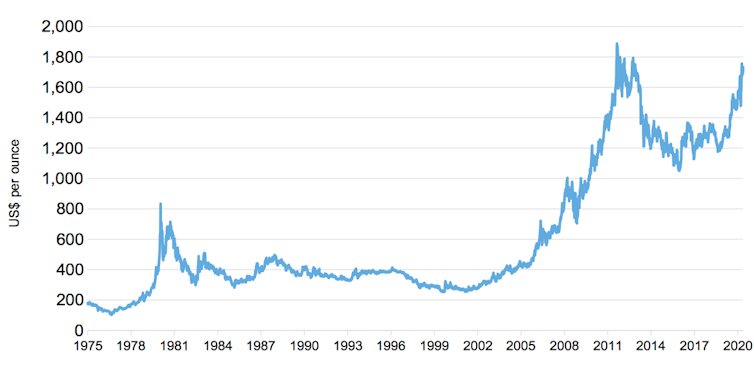

With gold and other commodities, the market convention is that prices are based on the prices of the futures contracts that will mature the soonest. Using these prices, the chart below shows how gold has traded over the past 45 years:

Gold price 1975-2020

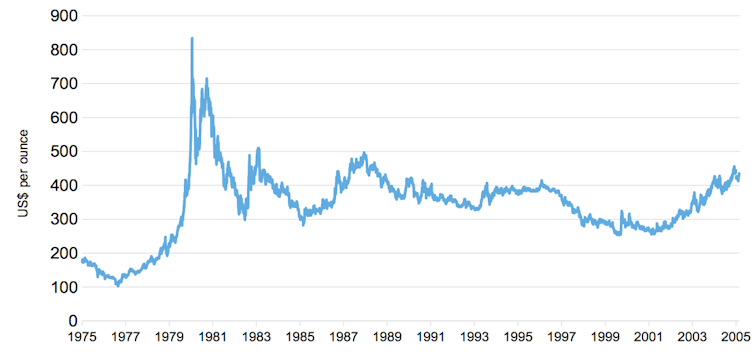

You can break this chart into four different periods. The first is the longest, running from January 1975 to February 2005. In this period the price went up and down but always reverted to a mean average of around US$400 per ounce.

The only notable exception was 1979-80, where it reached about US$820. This could be explained by a surge in crude oil prices, and hence inflation, over the same period, which was in the aftermath of the Iranian revolution. Both crude oil and gold eased back down subsequently.

1975-2005: the long moderation

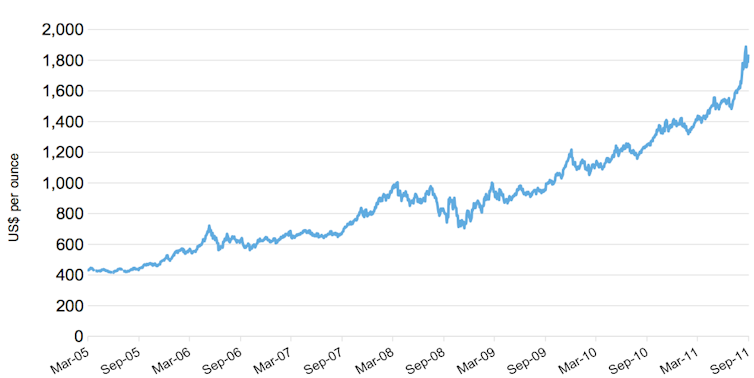

The period from February 2005 to August 2011 saw a pronounced increase in the price – barring a decrease over the second half of 2008 during the global financial crisis. This period spans the so-called 2005-08 boom, when commodity prices increased across the board. It was only the third boom since the 1950s. Possible explanations include greater demand from emerging economies such as China and India, as well as a flow of investor money into commodity indices.

2005-2011: the commodity boom

From a peak in August 2011 until mid-September 2018, gold fell again – from US$1,870 to the US$1,050 low of December 2015. For some, this came as no surprise because the previous period’s run-up was a bubble. From 2016, gold began tracking a mean level of around US$1,200, where it eventually ended in September 2018.

2011-2018: the slide back down

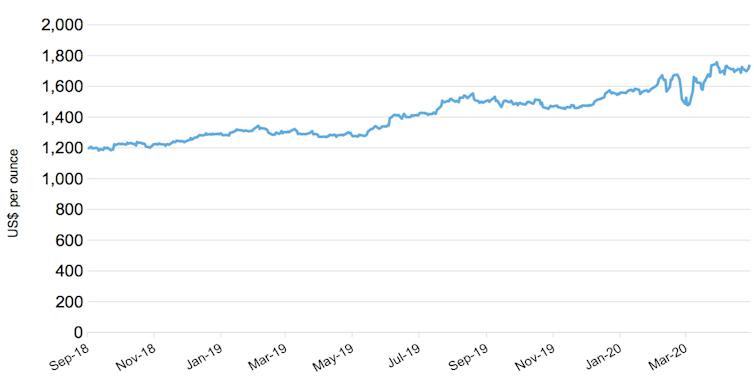

Gold has since been going up again. Notice that the increase since the beginning of 2020 is part of a longer upward trend. In other words, it should not be attributed only to the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, the price remains above the 2020 average of around US$1,620, but still not above its all-time high of US$1,888 in August 2011. So while it may keep rising, history shows that periods of decline are not unprecedented.

2018-present: new momentum

What drives gold prices

Whether gold will continue going up depends on various factors. Decisions of central banks on interest rates and inflation affect the price of the metal, since lower interest rates and higher inflation both make it more expensive. The same goes for exchange rates, in the sense that a weak US dollar will cause gold to rise. Then, there is supply and demand of the metal itself – gold mining is becoming more difficult over time, which is one reason for long-term increasing prices.

All these will have a bearing on investors deciding to buy or sell gold futures or the exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that trade in the commodity indices which include the precious metal. Also important is the level of uncertainty about the future of the economy, since gold is considered a safe haven in troubled times.

Gold has enthralled humanity since ancient times. Still it glitters from central bank vaults to jewellery bazaars the world over. The Conversation brings you five essential briefings by academic experts on the world’s favourite precious metal. For more articles written by experts, join the hundreds of thousands who subscribe to our newsletter

But as to how each factor exactly influences gold, the academic literature shows very mixed results for some of them. For instance, since the so-called commodity boom in 2005, there has been a heated debate about whether gold prices (and commodities more broadly) are driven more by economic fundamentals or by the behaviour of speculators and ETFs.

This turns on whether gold is essentially a financial product or a physical commodity. As with most things, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. I have been involved in this research, for instance co-authoring findings that the margins that brokers charge on gold futures contracts can affect prices. In another paper, we documented that prices can be affected by the level of inventories of commodities –meaning how much is being held in storage – and the extent to which people are hedging against their prices going up or down.

Should you buy gold?

We found that investors who included gold in their portfolios alongside stocks, bonds and cash were better off in the period from 1989 to 2009. This was true even after the risk of investment and the transaction costs are taken into account.

Interestingly, this is not the case when investors start adding other commodities, such as cotton, copper and live cattle. This highlights the distinct characteristics of gold and other commodities, to the extent that there is arguably no such thing as a commodity asset class – as I have emphasised, among other commodity investment pitfalls, here. Instead, gold and crude oil seem to perform distinctly from the rest.

Forecasting asset prices has never been easy, however, and investors always need to be cautious. To the extent that there is more uncertainty to come about the prospects for economic growth, including from COVID-19, and if low interest rates prevail, gold prices may well continue to rise. The more negative news on economic growth, the greater the increase in the price of gold.

Even then, the direction of travel may not be straightforward. If bad news causes stock markets to fall again, investors may well sell off gold and other commodities to finance their losses in other assets. This will put a downward pressure on gold prices.

Equally, the situation may well change if the current uncertainty is resolved. For example, if a viable medicine for COVID-19 is developed, and/or the USD dollar strengthens, gold could move in the opposite direction. The 2011-2018 decline in gold prices, following a bullish period, is a good example to keep in mind.

If you liked this article, find more expertise in our gold series:

Countries went on a gold-buying spree before coronavirus took hold – here’s why

Long before COVID-19, countries have been buying new reserves and bringing it home from overseas storage to an extent never seen in modern times.I’m a bit of a modern-day alchemist, recovering gold from old mobile phones

There’s 33 times more gold in the average handset than in the equivalent amount of ore. Yet the vast majority is never recovered.Meet the struggling gold miners who are missing out on the boom in precious metals

You would think that anyone in the gold industry would be getting rich right now, but informal miners in many countries are missing out.How the US government seized all citizens’ gold in 1930s

It seized all gold bullion and coins, forcing citizens to sell at well below market rates. Then, immediately after the “confiscation”, it set a new official rate for gold that was much higher.Subscribe to our newsletter

Get more news and information you can trust, direct from the experts.

George Skiadopoulos is also a Professor of Finance at the University of Piraeus, Director of the Institute of Finance and Financial Regulation (www.iffr.gr) and Honorary Senior Visiting Fellow at City University of London. He has received funding from the J.P. Morgan Center for Commodities, at the University of Colorado Denver Business School (Commodities Research Fellowship Award) to conduct the research for one of the cited papers (Daskalaki, Skiadopoulos and Topaloglou (2017, Journal of Empirical Finance)).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.