Eastern European food is often associated with meat, but travel along the Danube river, and the regions it weaves through at it’s most easterly point, and you might be surprised at the prevalence of plant-based cuisine.

“Romanian, Bulgarian, Serbian, by which travellers have associated a lot of meat, because the menus in the restaurants are different to the ones people cook at home,” says cookery writer Irina Gerogescu. Bar the odd treat or celebration, home kitchens in this region are much more likely to be enjoying vegetables.

“Almost everyone at the back of the house has a little vegetable garden. The temperatures in the summers are very high, it’s a haven for tomatoes. It has the right climate for vegetables; a lot of runner beans, garden, peas, peppers, aubergine.”

Leeks may be better known to us as a national food of Wales (where Georgescu now lives having moved from Romania to the UK 15 years ago) but they were loved by the Romans too, becoming a culinary symbol of Oltenia, in the south of the country – and part of many national dishes, including eggs with sautéed leeks for breakfast.

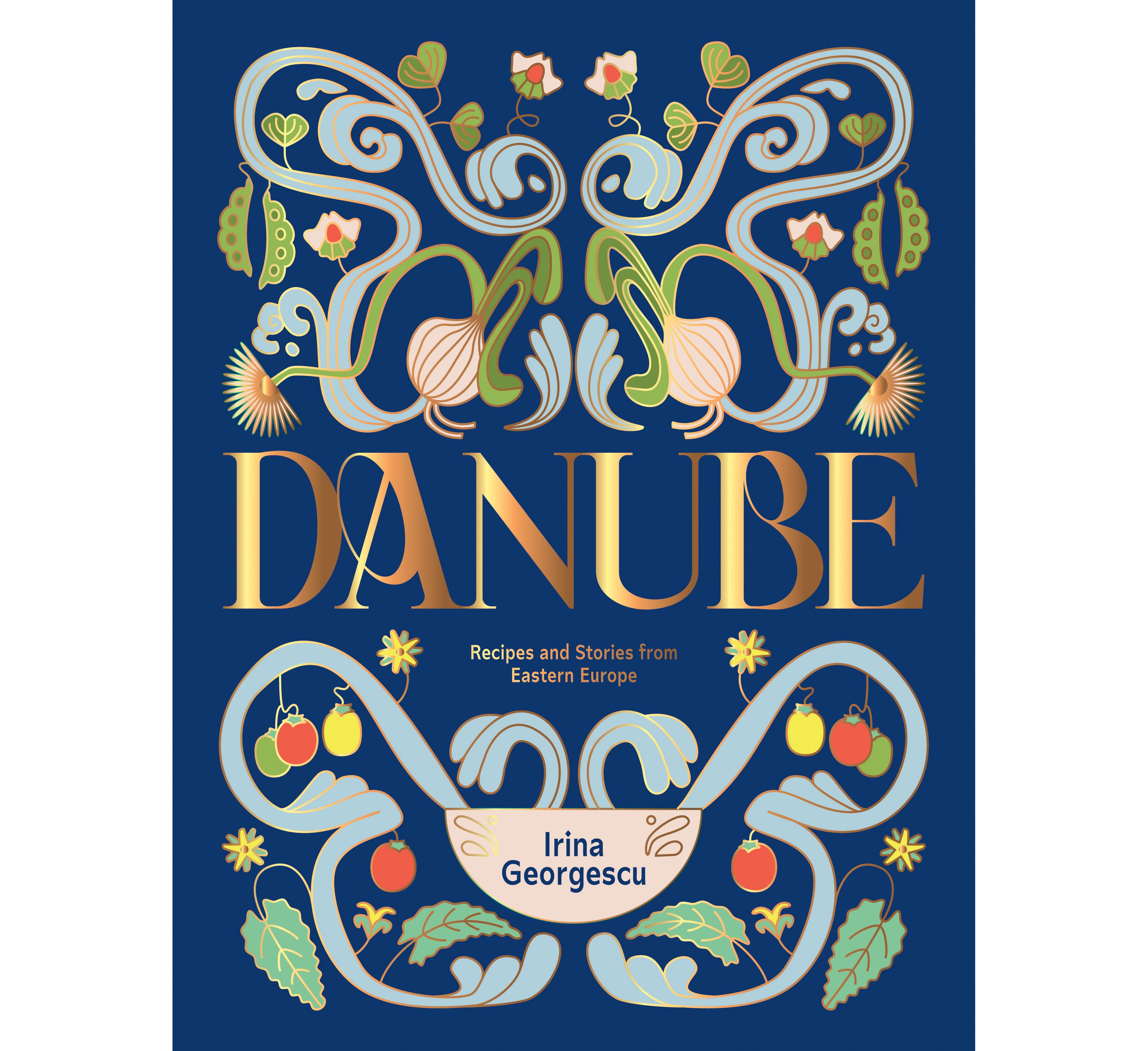

It’s why 90 per cent of the dishes in her latest cookbook Danube – which focuses on the cuisine influenced by this side of river and the lands upon which it laps – are vegetarian. “I wanted to select those dishes that are very popular, but you won’t find them in a restaurant.”

Beginning in the Black Forest of Germany, the Danube goes through 10 countries, “When it enters Romania [through The Iron Gates gorge] it turns into a border between Romania and Serbia, further east is Bulgaria, and then it turns into the beautiful Danube delta, a Unesco site, and flows into the Romanian Black Sea,” says Georgescu. And it’s this side of Eastern Europe and its food, influenced by a complex history and an eclectic ethnic fabric, the she wants to celebrate.

Gerorgecu grew up in Romania’s capital Bucharest, a family of four in a small, one-bedroom home. But her grandmother hailed from Transylvania, in central Romania, and her grandfather’s family from Oltenia.

“We used to talk about some of the dishes of the south, and my grandmother used to just guess how they were made because we didn’t have cookery books or anything like that in those times,” recalls the 48-year-old.

The communist regime fell when she was 12, so before that some of her earliest memories of food in her home country include “queuing to get oil, butter, or nothing – sometimes queuing for hours and you’d have nothing in the end because the supply in the shop had finished”. So often cooking involved making whatever was possible out of what they had, during the times when electricity, gas or water was available.

“I have a lot of memories, especially before the regime fell, of preserving. It’s a national sport! We have to eat later in the year, so we had compotes, jams, slow-cooked roast peppers, aubergine, onions – put that in a jar and have it for the rest of the year. Fermented pickles, fermented tomatoes, fermented cabbage – because otherwise you wouldn’t have the national dish for Christmas and Easter called sarmale (cabbage rolls).”

So important, in fact, that her family kept a big barrel of brined cabbage, pickles and sauerkraut on their balcony so there was a constant supply. “Without sarmale you couldn’t have Christmas to be honest!” she laughs.

Meat was rare. “My uncle lived in Transylvania, so every December we would drive for six to eight hours to him to pick up a pig. He would prepare the pig in two days, we put it in the car and took it back to our apartment. There was not a lot of food around – for us, that was the shopping.”

Cornmeal (or polenta) was – and is still – an important staple in Romania; hot, creamy polenta with jam for breakfast, cold polenta sliced like bread and served with soup, or chopped thin into layers for a version of lasagne.

Historically, wheat was very precious, she explains, maize isn’t as expensive and easier to grow on hilly areas. It was introduced in these lands in the 17th century during the Ottoman Empire and it wasn’t taxed so landowners were encouraged to plant corn to feed the poor, and as a “plan B” if the wheat crop failed. “And this is how we ended up with so many cornmeal dishes in our cuisine,” Georgescu says.

When flour ran out in UK shops during the coronavirus pandemic, “Cornflour remained untouched” – so she started an online cooking class to teach people how to make cornbread in lockdown.

But you can’t have a Danube cookbook without a few fish recipes. From the river, carp, catfish and trout are all key ingredients. “You will see the connection between the land and the river and the dishes, the influence that massive river had on the people around the river and in the Delta, because [here] the meat is replaced with fish,” says Georgescu – think moussaka made with fish (musaca de peste).

The river may be a political border today, but historically it was a route for trade and migration, “It was how Greek colonies travelled in the first centuries of our time,” she notes. “The river was always important.”

And now, there are many campaigns for bridges to be built across it, she says; they want to shop, attend festivals and eat, across the river bank in Bulgaria or Serbia. “It’s an interesting way that we’ve come around”, people are “wanting to be connected by, not separated by, the river.”

‘Danube’ by Irina Georgescu (Hardie Grant, £28).