On 3 November 1948, Julia Child and her husband Paul sat down for lunch at La Couronne, a venerable restaurant opened in 1345 in the Normandy capital of Rouen. Julia, a native of California, worried she “didn’t look chic enough” for the venue.

Her husband Paul, an American civil servant from New Jersey, was about to start a new job as an exhibits officer for the United States Information Agency, a now dissolved branch of the State Department. (Julia would later describe the position in her memoir My Life in France as “a sort of cultural/propaganda job”, through which Paul would “help promote French-American relations through the visual arts”.) The two had just arrived in France after days on the SS America, an ocean liner. Julia had never been to Europe before.

Paul, who spoke fluent French, took over ordering duties. The Childs enjoyed oysters on the half-shell with “a sensational briny flavor and a smooth texture that was entirely new and surprising”, paired with rye bread and butter. They drank Pouilly-Fumé, a dry white wine from the Loire Valley. After the oysters came their entrée, sole meuniere: a large Dover sole that arrived “perfectly browned in a sputtering butter sauce with a sprinkling of chopped parsley on top”.

Sole meuniere is a stripped-down dish. Like a plain croissant or a roasted chicken, it leaves the cook no room to hide: their technique is on full display. When done well, it can be sumptuous. La Couronne’s sole meuniere, per Julia Child, was “perfection”. Green salad and baguette followed, then fromage blanc (a French dairy product similar to yogurt that has no English-language equivalent) and coffee.

“Our first lunch in France had been absolute perfection,” Julia Child wrote in her memoir. “It was the most exciting meal of my life.”

In the mythology of Julia Child, the sole meuniere is regarded as the dish that birthed a legend. Two years after her lunch at La Couronne, she enrolled in culinary school, setting off on a path that would see her become one of the most famous cooks and connoisseurs of French cuisine in America. She has also become a prominent cultural figure; the kitchen she kept at her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts (once returned from Paris) is on display at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. Her debut cookbook Mastering the Art of French Cooking, published in 1961 by Alfred A Knopf, is widely considered a classic and has been credited with shaping both the cookbook industry and American food culture. Julia Child’s cooking show, The French Chef, remains available to stream to this day, six decades after it first aired.

Julia Child’s story, at the intersection between the worlds of food, publishing, and, well, France, has been told many times. There was the 1989 one-woman play Bon Appetit!, in which Jean Stapleton portrayed Child herself. On the big screen, there was the 2009 film Julie & Julia, based both on Child’s own existence and that of blogger Julie Powell, who once resolved to cook all the recipes in Mastering the Art of French Cooking over the course of a year. The latest addition to the genre is Julia, a new HBO Max series focusing on the development of The French Chef and Julia Child’s introduction to the world of television.

Born in 1912 and raised in a “comfortable, WASPy, upper-middle-class family” in Pasadena, California, Julia Child grew up eating “typical American fare”, “delicious but not refined food”. During the Second World War, she worked at the Office of Strategic Services (a now-defunct intelligence agency, replaced by the CIA and the Bureau of Intelligence and Research). There, she met Paul Cushing Child, 10 years older than her, raised by “a rather bohemian mother” who had herself lived in Paris. Paul had travelled the world, “spoke French beautifully”, and “adored good food and wine.”

Two years after moving to Paris with Paul, Julia enrolled at Le Cordon Bleu, a culinary and hospitality school founded in 1895. She earned her diplome de cuisine, a classical training course, in 1951. With two French cooks, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle, she wrote Mastering the Art of French Cooking, a comprehensive yet accessible bible of French cuisine. The book was originally contracted to publisher Houghton Mifflin, but the project fell through. It was Judith Jones, an editor at Knopf who had lived in Paris after college, who ultimately championed it.

Jones, as she would later recall in her own memoir The Tenth Muse: My Life in Food, had been hired mainly to work with translators of French authors such as Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. She was disillusioned with the state of food in America – the ingredients, she told Eater in 2015, were “hideous”. “It was a low time in cookbook writing in America, and there was also the fact that there didn’t seem to be an audience for them,” she said.

The manuscript of Mastering the Art of French Cooking seemed like an unbelievable gift. “I just couldn’t believe it. It was as though somebody sent a present for me,” she said. During an editorial meeting, Alfred Knopf, who in 1915 had co-founded the publishing house with his wife Blanche Knopf, said Jones should “have a chance” with the project.

“That was the beginning of it,” Jones said. “I mean, it was just magic.”

Mastering was “the cookbook I had been dreaming of”, the editor (by then a legendary name at Knopf) wrote in The New York Times in 2004. “It spelled out techniques, talked about the proper equipment, necessary ingredients and viable substitutes; it warned of pitfalls yet provided remedies for your mistakes. Moreover, although there were three authors, it was the voice of the American that came through, someone who was clearly a learner herself, who adored la cuisine Française and was determined to dissect and translate it for an American audience.”

Almost 50 years after the book’s publication, Hollywood introduced Julia Child to a new generation of fans. Julie & Julia, released in 2009, featured Meryl Streep as Julia and Stanley Tucci as Paul. Amy Adams starred as Powell, the blogger and author whose book Julie & Julia: My Year of Cooking Dangerously provided half of the inspiration for Nora Ephron’s screenplay (the other half came from Child’s own My Life in France). The film resulted in an Academy Award nomination for Streep in the Best Actress category (Sandra Bullock won that year for her performance as Leigh Anne Tuohy in The Blind Side).

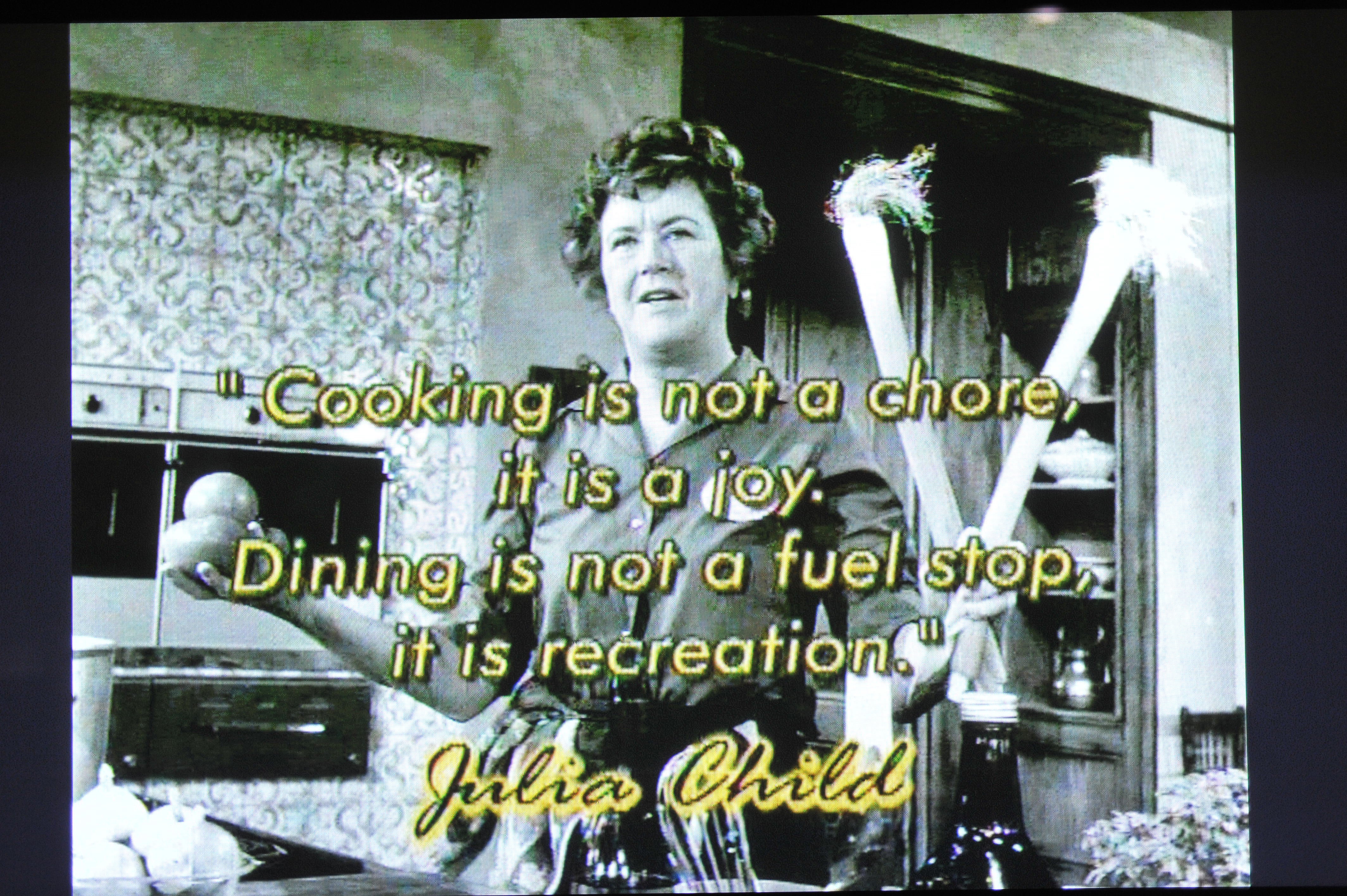

Julia Child died in 2004 aged 91. There is a timeless appeal to her story, brought to life again and again by her sincere love of food. Watch The French Chef and you will see that her appetite for French cuisine was both literal and intellectual. She approached it like an enigma to be solved; she wanted, needed to know how to perfect every dish. She did so with a rare mix of perfectionism and self-forgiveness, gracefully acknowledging mishaps in front of the camera.

“If you’re alone in the kitchen, who is going to see?” she rhetorically asks viewers in an episode of the cooking show titled The Potato Show. She has just attempted to flip a potato pancake without any utensils, with just an energetic nudge of the pan. “When you flip anything, you really just have to have the courage of your convictions – particularly if it’s sort of a loose mass like this,” she tells the camera. When her attempt to flip the pancake proves only partially successful, she doesn’t lose a beat: “See, when I flipped it, I didn’t have the courage to do it the way I should have. … But the only way you learn how to flip things is just to flip them.” The kitchen becomes a place both of rigorousness and playfulness.

“Things happen in life,” Jones told Eater two years before her own death in 2017. “Julia once said to me, and I’ve quoted her on this, ‘Judith! We were born at the right time.’ And I said, ‘Yes, Julia, but we had to act on it.’ And she said, ‘Right you are!’”