British-born Chinese TV chef Jeremy Pang says the food of Hong Kong was a “massive influence” in his household growing up.

His parents both grew up in Hong Kong – a special administrative region of China which was under British rule for 156 years until 1997.

“My mum and dad lived in the UK from the Sixties, but when it came to them cooking Western food, they were terrible at it. They cooked the food of their culture and where they grew up, so we grew up eating Cantonese cooking, food from Hong Kong.”

It is known for being the fourth most densely populated region on the planet and home to some of the world’s tallest buildings with sky-high restaurants and an even richer casual dining and street food scene.

Pang and his sister would travel back to Hong Kong for a month or two at a time. “It was like a second home to us, and whenever we were there we were constantly out with friends and family, eating our way around the city. My dad [who died in 2009] was the type of person who wasn’t keen on really high-end restaurants – he likes local.”

A new six-part ITV show, Hong Kong Kitchen, sees Pang travelling through the city and discovering food with some famous faces – including Mel Giedroyc and Simon Rimmer. “Food, to someone with Chinese heritage, is both a source of happiness and a tool which we use to build relationships and trust with others,” he writes in his new book, also titled Hong Kong Kitchen.

Hong Kong cuisine might be familiar to you

“I think most people don’t realise that most of the Chinese food we’re used to eating in the UK would have originated from Hong Kong and the Canton region [of the south],” says the 41-year-old. “So things like your classic sweet and sour porks and black bean beef, or chow mein. Fried noodles, those dishes are very much Cantonese cuisine.”

Compared to other regions, Hong Kong food has a more mellow flavour, he explains. “There’s not as much of a constant chilli flavour that people are used to from Sichuanese food, for example, in Hong Kong we’re very much reliant on fermented soybean flavours.”

Some of the key ingredients in Hong Kong dishes are light and dark soy sauce, oyster sauce and sesame oil, along with ginger, garlic and spring onion, says Pang: “Quite simple ingredients that can be used to make up hundreds of different dishes.”

The country’s food scene is unique

“Hong Kong has a very eclectic mix of cultures, and the food culture is everywhere and it surrounds you,” says Pang. “As soon as you land in Hong Kong, you smell food coming out of the restaurants.

There are many different types of Hong Kong diner; from Cha Chaan tengs (tea house lounges) and Dai pai dong ( a type of open-air food stall) to dim sum houses only serving dumplings on moving trolleys.

“That’s the beauty of it, it’s got this massive eclectic mix [but] you have Cantonese cuisine at its core,” says Pang.

“Cha Chaan tengs, have a sort of post-war, 1950s, what Hong Kong people thought Western food was like [vibe]. Things like French toast with a knob of butter on top and condensed milk. Or you might have a five spice pork chop, deep fried and put in a crusty roll.”

Here, you’d sip on “milk tea”, which Pang says is the national drink – “Essentially a builder’s brew, but made with evaporated milk and poured through a stocking. That’s very traditional.”

Dim Sum culture is massive

Dim sum is a traditional Chinese meal of small, bite-sized dishes including dumplings and buns.

“Hong Kong, is the place for dim sum – from little cafes and eateries all the way up to huge dim sum restaurants that could probably take 1,000 people at one time,” says Pang, who recommends ordering 50-60 for a group of four people.

“In the West, dim sum eating culture is more of a lunchtime thing. In Hong Kong, these dim sum restaurants will be open from the early hours in the morning all the way through to midnight. Quite often the restaurants do 50 per cent off from 6am to 9am, so older people go there with their newspapers and have a bit of a gathering, it’s quite a community.

“It’s such a big part of our culture, and that sort of sharing element of eating.

Dumplings are easier to make than you think

“The intricate folding of dumplings came from the competitive nature of chefs,” explains Pang. So although they might look difficult to emulate, “if you have ready made dumpling pastry and a good recipe for the filling, then as long as you can squeeze it together, who cares what it looks like?

“Most of the time, if you squeeze it together in one way or another, it will look like a little gold sack anyway. I think it’s actually quite hard to make a dumpling wrong.

“One of the best places in Hong Kong is in Wan Chai, called Northern Dumpling Yuan. That place does 10 to 15 different types of dumpling but they’re all the same dumpling, with different fillings and they don’t do anything fancy with the folding at all.

“The fillings are mainly driven by the flavour of the vegetable, they might have watercress dumplings or celery dumplings – Chinese celery is quite strong in flavour. Or fennel and beef mince, very simple flavours.”

When cooking at home, “it’s really nice to make it with other people, because A, it’s fun and B, like, you can make them quicker. So this is sort of thing that I get the kids involved with.”

For stir-fries, don’t throw everything in together

Stir-fries might be student staples but Pang says cooking them well is “more intricate than people think”. The concept of a “wok clock”, is the placing of prepared and chopped ingredients around a plate, in accordance to the order in which you’ll add them to the pan. “Putting certain ingredients in first, second, third, fourth, fifth, that clock thing will give you so much more confidence you hadn’t realised you’d taken in from just one recipe and then the rest won’t feel daunting at all.”

Understanding heat is key

“Chinese food, no matter whether it’s stir-frying or not, it’s all about understanding heat, and when you’re confident with that, you can cook anything,” says Pang.

“Even if you’re braising something. If you threw everything into a pot with all the liquid all at the same time, it would just boil something. Whereas if you’re properly braising, you’re hammering the flavour of a glaze or sauce into your meat or veg first before you bring more liquidised stock or water into that braise later on, to make the meat more succulent over time.”

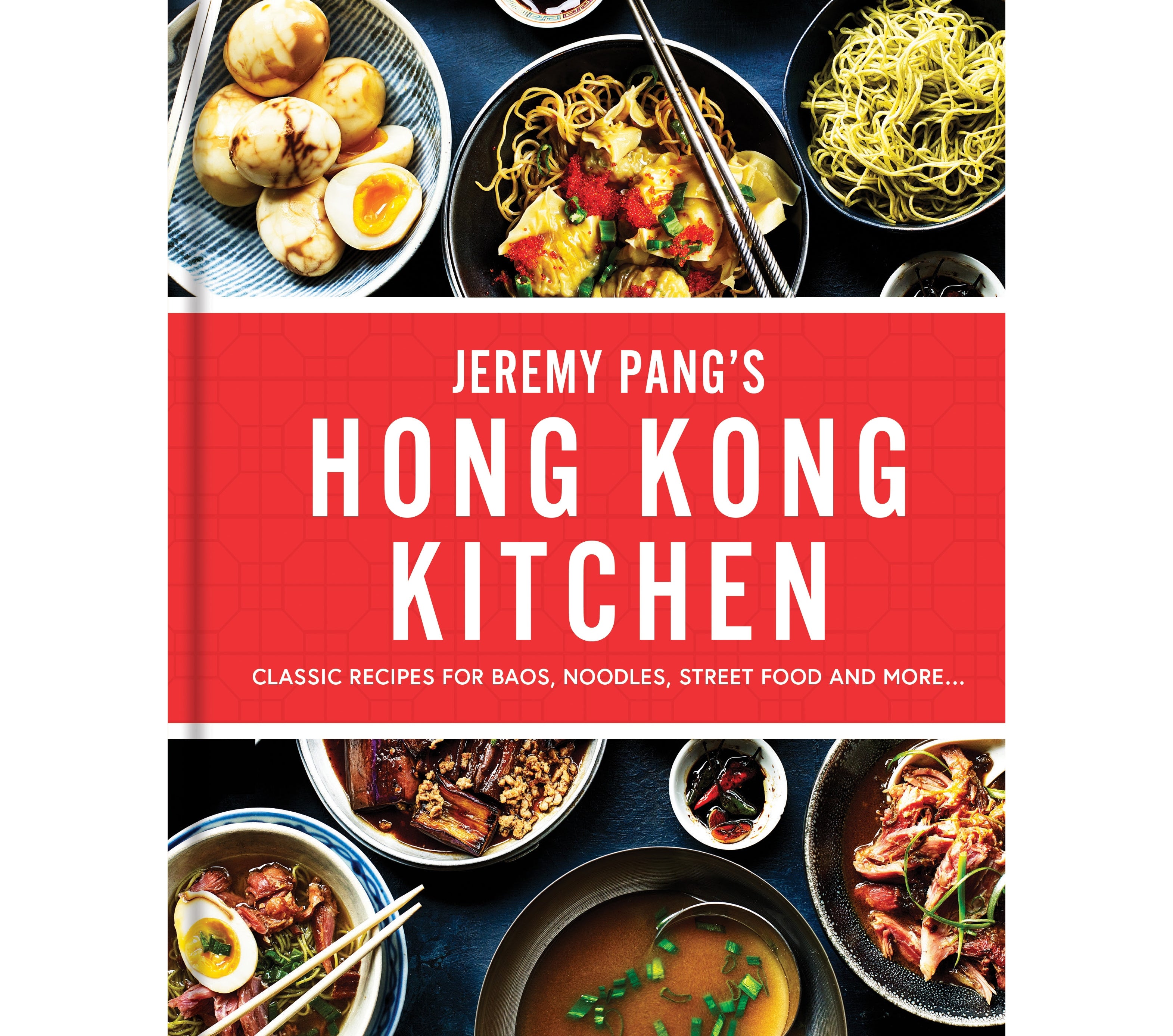

‘Hong Kong Kitchen’ by Jeremy Pang (Hamlyn, £25).