The Reserve Bank has announced a temporary reprieve for mortgage holders, leaving interest rates on hold at 3.6 per cent after 10 consecutive months of rises.

But RBA governor Philip Lowe says "some further tightening" may be needed to bring inflation back into its target range of 2 to 3 per cent.

Following the decision, the Australian dollar fell slightly, while the local share market crawled to a fresh three-week high.

Follow all the updates and reactions to the RBA's interest rate announcement on our blog.

Disclaimer: this blog is not intended as investment advice.

Key events

To leave a comment on the blog, please log in or sign up for an ABC account.

Live updates

Market snapshot at 4:10pm AEST

By David Chau

And that's a wrap!

By David Chau

Logging out now at the end of another busy day in finance and business news.

Kate Ainsworth will be with you early tomorrow, and she'll take you through some interesting developments.

For starters, the Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe will address the National Press Club (and he'll no doubt be pestered with questions about where Australian interest rates are headed).

On top of that, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand is expected to slow down its interest rate hiking cycle (with economists anticipating a 0.25 percentage point increase tomorrow).

Coal and gold stocks surge ... as tech and lithium falls behind

By David Chau

In case you were wondering, here's a list of the top 10 (and worst 10) stocks on the ASX 200 today.

The biggest gains were seen in coal miners Whithaven Coal and New Hope Coporation, and gold stocks like Ramelius Resources, Gold Road Resources and West African Resources.

They helped lift the Australian share market by a measly 0.2% by the end of the trading day.

But it wasn't a good day for lithium, electric battery and tech-related stocks, including Sayona Mining, Core Lithium, Lake Resources and Megaport.

Why do we care what the US Fed is doing?

By Gareth Hutchens

Why does the RBA look to the US rates hikes when making decisions about Australia? When a fixed rate home loan in the US is for 25-30 years and in Australia is between 1-5 years, surely thats comparing apples with oranges and the impact on households would be significantly different.

- Jason

The RBA keeps on eye on what the US Federal Reserve is doing with interest rates because they impact the value of Australia's dollar.

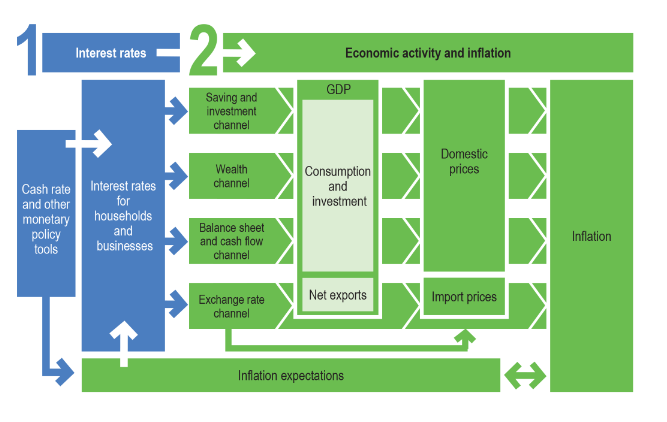

I've posted a link (below) to a handy explainer from the RBA.

It explains the different ways in which interest rate movements impact economic activity in Australia.

It includes this graph, which shows how interest rate movements flow through Australia's economy in different ways.

If you look near the bottom of the graph, you'll notice a box that says "exchange rate channel."

And you'll see how that exchange rate channel affects "net exports" and "import prices" and finally, "inflation."

That's the part of the monetary policy process that involves the US Federal Reserve.

And that's why the RBA keeps on eye on what the Fed is doing.

This is how the RBA explains it:

The exchange rate can have an important influence on economic activity and inflation in a small open economy such as Australia.

It is typically more important for sectors that are export oriented or exposed to competition from imported goods and services.

- If the Reserve Bank lowers the cash rate it means that interest rates in Australia have fallen compared with interest rates in the rest of the world (all else being equal).

- Lower interest rates reduce the returns investors earn from assets in Australia (relative to other countries). Lower returns reduce demand for assets in Australia (as well as for Australian dollars) with investors shifting their funds to foreign assets (and currencies) instead.

- A reduction in interest rates (compared with the rest of the world) typically results in a lower exchange rate, making foreign goods and services more expensive compared with those produced in Australia. This leads to an increase in exports and domestic activity. A lower exchange rate also adds to inflation because imports become more expensive in Australian dollars.

The verdict: one more rate rise or is this the end?

By Sue Lannin

Hi, I've been away for a bit reading all the reaction to the Reserve Bank keeping rates on hold at 3.6 per cent today after 10 rate rises since May last year.

I haven't seen so much reaction to official rates remaining unchanged ever!

Anyway, I digress so let's cut to the chase.

Capital Economics reckons the "RBA will deliver one final rate hike in May."

Abhijit Surya, Australia and New Zealand economist says:

"The Reserve Bank of Australia kept open the possibility of further tightening when it decided to leave its cash rate unchanged at 3.6 per cent today."

" As such, we do still expect the RBA to deliver one final 25 basis point (0.25 per cent) rate hike in May before bringing its tightening cycle to a close."

And here's veteran rate watcher Bill Evans, chief economist at Westpac, who is also forecasting a final rate rise next month as well.

"I expect that we will see another rate hike at the May board meeting, but the pause today was to collect more information and wait for a more accurate measure of inflation."

"I think when they talked about the disruption in the US banking system, they pointed out to the fact that there's likely to be a reduction in the availability of credit, which represents a headwind for the global economy."

"But they did point out that the Australian banking system remains strong."

"So any transmission from credit contraction in the US to Australia is considered to be unlikely."

UBS chief economist George Tharenou is also predicting a possible 0.25 percentage point rate rise next month.

"Only a few weeks ago UBS was one of few with an on-hold view, but, financial market volatility then materially lowered expectations (which previously almost priced a 25 basis point hike), while another weaker monthly CPI (Consumer Price Index) indicator in February also scaled back expected hikes. "

"Overall, the RBA retained a 'tightening bias', as we expected, but was on the dovish side, by adding the prefix "some" when guiding to "further tightening of monetary policy may well be needed to ensure that inflation returns to target"; and softened the "will" to "may well".

"The RBA also added a 'time-condition' when holding this month, which suggests to us the April hold was more of a 'pause rather than a peak.'"

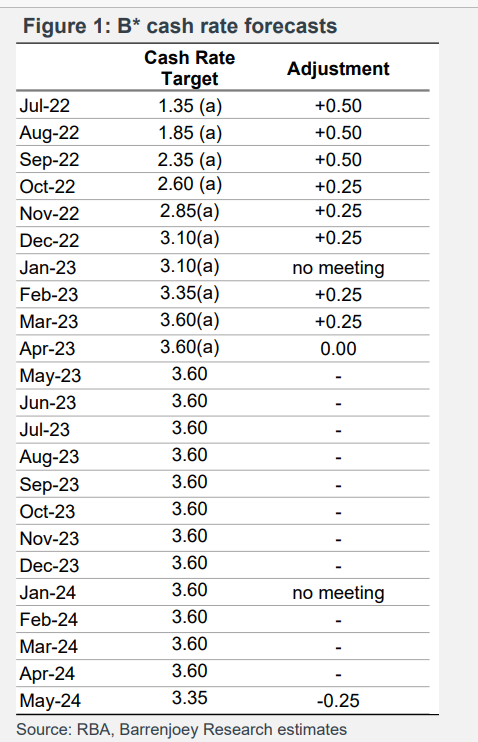

But Barrenjoey Chief Economist Jo Masters thinks the RBA is done raising rates.

"We revised our interest rate profile for a terminal cash rate of 3.6 per cent with some prospect of a rate hike later this year if the economy does not evolve as expected."

" This takes our cash rate forecast back to where it was before February’s hawkish tilt. "

"We expect the RBA will revise growth lower and bring forward a 3 per cent inflation rate when forecasts are updated for the May Statement on Monetary Policy,."

" We continue to think the persistence of inflation will require restrictive settings for some time, with the conditions for a rate cut unlikely to emerge before May 2024," Ms Masters said.

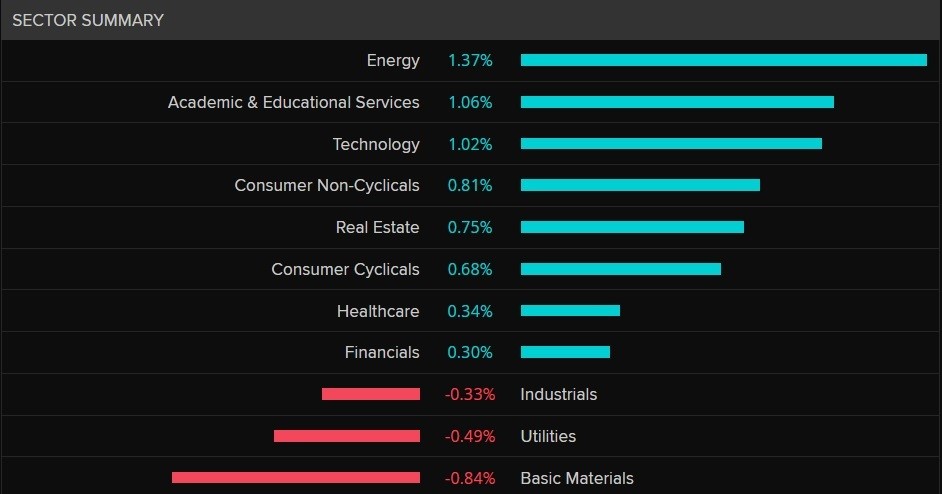

Energy stocks boost the ASX ... once again

By David Chau

Let's take a deeper dive into the stock market's performance today.

The ASX 200 has risen for its seventh straight day. With today's gain of 0.2%, the benchmark index has risen to its highest level in three weeks.

Most sectors posted gains, with energy being the standout performer.

That's after oil prices rose again after Saudi Arabia and the other OPEC+ nations surprised the market with a cut to their production levels.

At the other end of the spectrum, materials was the worst performer.

It was driven by falls in the share price of mining giants BHP (-2.2%), Rio Tinto (-0.9%) and Fortescue Metals (-0.7%) after a steep fall in iron ore prices.

What about alternative ways of controlling inflation?

By Gareth Hutchens

Adjusting the official interest rate impacts the demand for consumer goods by pulling money out of the economy, but it's almost all money that those with debts (mortgages) suffer. Is there any mechanism (RBA or other) that can modify the spending patterns of those who have paid off their houses and are spending savings accrued during the pandemic?

- Nathan

This is another great question.

I wrote a piece recently about an idea from John Maynard Keynes. He had the idea of using a compulsory savings mechanism to tackle inflation.

He suggested that, during an inflationary episode, we could quarantine a small portion of everyones' income each week, so people would have less money to spend at the shops, and then once the inflationary wave had passed everyone could get their money back in installments (with interest).

That way, you're tackling inflation by postponing peoples' ability to spend money (while still allowing workers to keep the money they'd worked hard for), rather than eliminating their ability to spend money (by lifting interest rates to transfer money from households to banks as a financial rent).

It was a fascinating idea.

If it makes you think of our compulsory super system, you'd be right. We introduced compulsory super in the 1980s and 1990s as part of a suite of policies to clamp down on the high inflation of the 1980s.

But the difference is, we don't use our compulsory super system to manage irregular episodes of high inflation. It just sits off to the side, taking a regular portion of our weekly income regardless of the state of the economy and inflation.

Could we use a separate compulsory savings mechanism to manage periods of high inflation?

I don't see why not.

But it would have to depend on what type of inflation we're talking about. If the inflation is being driven by rising wages and aggregate demand, then it could be an option.

But if the inflation is coming from supply chains and soaring commodity prices, like today's inflation, it wouldn't be the lever to use.

It all depends. But we should allow ourselves to think more creatively about this problem.

ASX rebounds after Reserve Bank's rate pause

By David Chau

Australian shares were flat (or slightly negative) for much of today, before the Reserve Bank's decision.

But some of the caution disappeared after the RBA confirmed market speculation that it would indeed keep its cash rate target on hold at 3.6%.

The RBA is also one of the first central banks in a developed nation to pause its tightening measures after Australia's inflation levels began to recede.

The ASX 200 index closed 0.2% higher at 7,236 points.

Gold stocks rose 2.9%, tracking gains in bullion prices, and were the top gainers on the benchmark stock index.

Sector giants Newcrest Mining and Northern Star Resources advanced 3% and 3.9%, respectively.

Energy stocks added 1.5% after oil prices jumped overnight on OPEC+'s plan to cut production further.

Sector heavyweights Woodside Energy and Santos rose 0.7% and 2.2%, respectively.

By 4:25pm AEST, the Australian dollar was trading at67.57 US cents, after falling by0.4%.

Interest rate lag explained

By Michael Janda

We hear a lot about interest rates and lag , so how long does it take for the interest rate decisions to actually take effect? Does it mean if the Reserve Bank has gone too hard and fast we won't know for months??

- Isaac

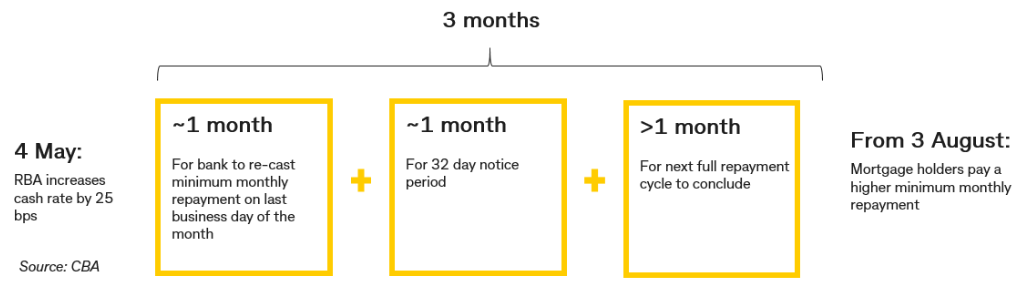

This is a great question Isaac, and there's two parts to the answer.

The first part is how long it takes for rate rises to affect existing mortgage borrowers.

Even for those on variable mortgages, this is generally at least two to three months.

Why?

Because the bank's usually set their rates to rise a couple of weeks after the cash rate does.

Then they have to reset minimum monthly repayment amounts and give customers 32 days notice of a rise in their minimum monthly repayments before that increase takes effect.

And then, because most people pay their mortgage monthly, it could be several more weeks before their next repayment cycle.

CBA's economists produced this useful flow chart showing how it took until August for the bank's variable rate customers to see the May RBA rate rise come out of their accounts.

(This doesn't mean you're not being charged the higher rate, it just means that extra interest is added onto your loan balance).

The net result is that most customers only started seeing December's rate increase coming out of their bank accounts last month and haven't felt the effect of the February or March rate rises yet.

Then there's all the fixed mortgage customers yet to feel any or all of the RBA's rate rises (although about half of them are rolling off their fixed loans this year, with many in for a big shock).

The second part is the general economic lag between a rate rise and its full flow on effects, which are manifold.

There's how long it takes to push up lending costs, how long that takes to make consumers and business change borrowing and spending decisions, the wealth effect as higher rates put downward pressure on asset prices, the import and export effects as the Australian dollar moves in response to rates, all of these things feeding into employment and wage effects, and so on.

As a rough rule of thumb, the RBA and most private sector economists reckon its at least a year to 18 months before a rate rise fully works its way through the economy.

So May's first rate rise probably hasn't even had its full effect yet, let alone the nine that followed it.

If you want more info, RBA assistant governor Christopher Kent recently spoke on just this topic:

The lag effect of interest rate rises

By Gareth Hutchens

We hear a lot about interest rates and lag , so how long does it take for the interest rate decisions to actually take effect? Does it mean if the Reserve Bank has gone too hard and fast we won't know for months??

- Isaac

Reserve Bank officials have said it will take between 18 to 24 months for the full effect of these rate rises to work their way through the economy.

So, when the final rate rise occurs (whenever that will be), that's when you should start your timer.

At the moment, there are still hundreds of thousands of households with mortgages that have yet to roll-over from fixed rates to variable rates.

Lots of them will do that this year, but plenty of them are waiting until next year for that to happen.

That helps to explain why it will take so long for these rate rises to be fully felt.

But having said that, we have to keep in mind that the RBA may even have to cut rates again this year, or next, if economic activity slows down so much that it will need stimulating.

Plenty of economists are forecasting that to happen. They say there will be rate cuts at some point of the next 12-18 months.

So, that complicates things further.

And in his statement today, RBA governor Philip Lowe drew attention to the fact that the string of banks collapses in recent weeks has put the global financial system under a lot of pressure:

"The recent banking system problems in the United States and Switzerland have resulted in volatility in financial markets and a reassessment of the outlook for global interest rates. These problems are also expected to lead to tighter financial conditions, which would be an additional headwind for the global economy."

So that's another element of uncertainty and unpredictability that could end up seeing the bank cut rates sooner than we were thinking.

Why do we rely so heavily on interest rate increases to tackle inflation?

By Gareth Hutchens

Why are they addressing the issues with rate rises? this is like using a sledgehammer for brain surgery. Surely there are better ways to reign in inflation using policy and targeted taxes.

- perplexed

Because this is the world we're living in.

After the RBA adopted an inflation target of 2-3% in 1993 and then asserted its "independence" from government, more and more responsibility for managing inflation (and the economic cycle itself) has fallen on the shoulders of the RBA.

This is the world economists and policymakers have built.

It suits the interests of politicians, because they can point their finger at the RBA whenever voters start complaining about rising interest rates and say "it's out of our hands, that's not our responsibility, it's the RBA's responsibility."

And plenty of economists also pushed for this particular arrangement, because they didn't like politicians manipulating interest rates, and they didn't think politicians were capable or agile enough to use fiscal policy (spending and taxing decisions) to manage inflation.

In the "Keynesian era" from 1945 to 1975, governments did use fiscal policy to manage inflation.

For example, in 1951, the "Korean War boom" helped to drive inflation up to 23.9% at one point.

Prime minister Robert Menzies (one of the founders of the Liberal party) said he didn't want to cut spending during that period, so he'd lift taxes instead.

In fact, he planned to collect enough taxes to produce a budget surplus (ie where he'd be taking more money out of the economy than he'd be spending into it) in a deliberate effort to suck inflation out of the system.

He lifted company tax, income tax, excise duty and sales tax, and he removed special depreciation allowances.

Now, the international financial system was very different back then. So was the structure of Australia's economy.

But that's just an example of how policymakers from the past thought about inflation.

And today, there have been calls from younger economists for policymakers to please start thinking more deeply about developing alternative ways of tackling inflation, that would depend on the source of each wave of inflation.

But for now, we're stuck with lifting interest rates up and down.

Watch: RBA pauses rate hikes for the first time in 11 months

By Kate Ainsworth

After months of pain for homeowners and borrowers, the RBA has given a slight reprieve by hitting the brakes on rate hikes for a month.

Business reporter Alicia Barry spoke to EY chief economist Cherelle Murphy about the RBA's decision and what it means for the economy moving forward.

Why are we always hearing from bank economists?

By Gareth Hutchens

Do economists have a bias to their employer when making predictions? I have noticed a fair amount of the national dialogue regarding interest rates is being led by economists from banks - is there a vested interest when providing commentary?

- Bill

Thanks Bill, this is a great question.

There are a few reasons why it seems like so much of the national dialogue about interest rates is being driven by economists from banks.

The major banks all have in-house teams of economists and analysts.

Their full-time job is to monitor economic and financial data and analyse what they're seeing, and part of that job involves making forecasts of key economic variables.

Lots of people in those economics teams have previously worked for Treasury or the Reserve Bank, so they're working with the same economic models as those institutions and they know how the people inside those institutions think.

And they're constantly publishing new analysis - week after week - as new economic data comes through from the Bureau of Statistics and other places.

For journalists, the research notes those economics teams produce are extremely useful and trustworthy. And they have people on-call to take questions from journalists at any hour. So that's why you'll see them quoted a lot.

But the economics teams are also set up to act independently from the rest of the bank. They don't take direction from their bank's executive teams or anything like that. They do give regular presentations to people inside the bank on where they think the economy's headed, but for the rest of the time they're just beavering away on their independent analysis.

However, it's also important for the media to remember that there are other economists out there.

One problem with over-relying on economists from banks is that they all basically use the same models, and produce very similar analysis and worldviews (with the odd exception).

In 1996, the RBA governor at the time, Bernie Fraser, even reminded journalists that they needed to speak to people outside the financial sector too.

Here's what he said in a speech to the National Press Club:

I think there is an important point here, and one which commentators might ponder next time they are rushing off to seek reactions to a change in monetary policy. Not only do financial markets participants have an understandable pre-occupation with low inflation, they also have more ready access to the media than people in other sectors of the economy with a probable greater focus on output and employment. The most notable feature of the survey of 32 economists conducted ahead of the recent interest rate cut was not that practically no-one picked the reduction, but that virtually everyone polled was from the financial sector.

Extremely important words, I think.

Whole year of hurt

By Sue Lannin

Reaction is coming in thick and fast after the Reserve Bank decided to pause official interest rates at 3.6 per cent after 10 rate rises since May last year.

Rate comparision website Mozo says it's been "a whole year of hurt" for mortgage borrowers.

It says the average mortgage rate has moved from 3.02 per cent in May 2022 to 6.12 per cent on April 1, 2023.

That means the average monthly repayment on a $600,000 mortgage has risen by $1,058 a month to $3,910.

"That adds to well over $10,000 extra since the Reserve Bank exploded out of the blocks with its first rate hike last May, just to keep a roof over the family's head," Mozo said.

Ouch.

Wages have definitely not gone up that much.

And Mozo's banking expert Peter Marshall says the pause in rates is cold comfort for borrowers.

“The increase in interest rates over the last year is a massive part of the cost of living crisis facing every Australian’, he said.

“For many the pain isn’t over, even though the RBA paused today, the rate changes are still filtering through to existing borrowers.

"So, it is worth calling your lender now to ask them what they can do on your rate."

“Our advice is ‘don’t be a hostage’, mortgages loyalty does not pay!”

RBA waits to see impact of previous increases as it leaves rates on hold

By Kate Ainsworth

After 10 consecutive rate rises, the RBA opted to wait and see how the economic data plays out, amid early signs that the increase in rates so far is starting to weigh on consumer spending and lower inflation.

Despite leaving the cash rate at 3.6% this month — still the highest level since May 2012 — RBA governor Philip Lowe was offering no assurances that interest rates would not rise again.

But Indeed Asia-Pacific economist Callam Pickering, who used to work at the Reserve Bank, said he expects the Australian economy to slow considerably over the second half of the year making further rate rises unnecessary.

"This is centred on the belief that household conditions will deteriorate due to the combination of much higher mortgage repayments, falling asset prices and the unprecedented decline in inflation-adjusted wages," he said.

"This is a recipe for an economic slowdown if ever I've seen one."

You can read more from business reporter Michael Janda below:

Watch: Finance Minister Katy Gallagher on the RBA's decision to pause rate rises

By Kate Ainsworth

She's speaking in Canberra now — you can watch live below:

What about Australian banks Governor Lowe?

By Sue Lannin

The problems in the global banking system, including the bail out of global banking giant Credit Suisse, and the collapse of US tech lender Silicon Valley Bank, have raised fears about another global financial crisis.

But Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe is trying to calm the horses at home:

"The Australian banking system is strong, well capitalised and highly liquid."(we heard this during the 2008 global finanical crisis as well from the RBA).

"It is well placed to provide the credit that the economy needs," Mr Lowe said.

And the RBA governor says it seems that sky high inflation is starting to come down.

"A range of information, including the monthly CPI indicator, suggests that inflation has peaked in Australia," Mr Lowe continued.

"Goods price inflation is expected to moderate over the months ahead due to global developments and softer demand in Australia."

"Meanwhile, rents are increasing at the fastest rate in some years, with vacancy rates low in many parts of the country. "

"The prices of utilities are also rising quickly."

"The central forecast is for inflation to decline this year and next, to around 3 per cent in mid-2025."

The latest Consumer Price Index data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics showed that the cost of living slowed in March from a year ago to 6.8 per cent, although the peak of inflation was higher than expected at 8.4 per cent over the year to December.

Mr Lowe also warned that the local economy is slowing down because of higher borrowing costs.

That is how central banks control inflation.

They make money more expensive, which forces consumers and businesses to stop borrowing and spending so much.

As they spend less, businesses earn less income, so firms stop expanding as much and hire fewer people, so the economy slows down.

Here's the RBA governor again:

"Growth in the Australian economy has slowed, with growth over the next couple of years expected to be below trend. "

"There is further evidence that the combination of higher interest rates, cost-of-living pressures and a decline in housing prices is leading to a substantial slowing in household spending."

" While some households have substantial savings buffers, others are experiencing a painful squeeze on their finances."

Mr Lowe notes that the unemployment rate remains near the lowest in 50 years, and many firms are finding it hard to find staff.

Although he concedes that as the economy slows down, then unemployment will go up.

And the RBA is closing watching out for a "price-wages spiral", that's when higher prices leads to pressure for higher wages to keep up with the rising cost of living.

"Wages growth is continuing to increase in response to the tight labour market and higher inflation."

"At the aggregate level, wages growth is still consistent with the inflation target, provided that productivity growth picks up. "

"The board remains alert to the risk of a prices-wages spiral, given the limited spare capacity in the economy and the historically low rate of unemployment."

"Accordingly, it will continue to pay close attention to both the evolution of labour costs and the price-setting behaviour of firms," Mr Lowe said.

And the RBA governor did not rule out more interest rate hikes if high inflation persists.

"The Board expects that some further tightening of monetary policy may well be needed to ensure that inflation returns to target. "

" In assessing when and how much further interest rates need to increase, the board will be paying close attention to developments in the global economy, trends in household spending and the outlook for inflation and the labour market."

"The board remains resolute in its determination to return inflation to target and will do what is necessary to achieve that," the RBA governor said.

RBA says 'further tightening' may be necessary to tame inflation

By Kate Ainsworth

In his statement, RBA governor Philip Lowe hasn't ruled out future increases to interest rates.

He says the RBA board's focus is still returning inflation to its target range between 2-3%, and future rate rises may be necessary.

"The Board expects that some further tightening of monetary policy may well be needed to ensure that inflation returns to target," he said.

"The decision to hold interest rates steady this month provides the Board with more time to assess the state of the economy and the outlook, in an environment of considerable uncertainty

"In assessing when and how much further interest rates need to increase, the Board will be paying close attention to developments in the global economy, trends in household spending and the outlook for inflation and the labour market."

"The Board remains resolute in its determination to return inflation to target and will do what is necessary to achieve that."

Got a question about interest rates? Now's your time to ask

By Kate Ainsworth

With the RBA pausing interest rates for the first time in 10 months, what would you like to know?

Now is the perfect time to ask, because business reporter Gareth Hutchens is here to help us make sense of it all.

Hit the big blue 'leave a comment' button at the top of the page, and he'll get back to you shortly.

(Similarly, if you're a borrower and simply want to celebrate the fact there wasn't a hike, you can use the comment button to do that, too.)

Philip Lowe explains why the RBA kept rates on hold

By Sue Lannin

In his statement, Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe says the board decided to keep the official cash rate steady at 3.6 per cent this month to provide extra time to assess the impact of the ten rate rises since May last year.

The RBA governor pointed to the problems in the global economy, including the recent banking crisis, which could also push up borrowing costs.

"Global inflation remains very high."

" In headline terms it is moderating, although services price inflation remains high in many economies. "

"The outlook for the global economy remains subdued, with below-average growth expected this year and next."

" The recent banking system problems in the United States and Switzerland have resulted in volatility in financial markets and a reassessment of the outlook for global interest rates."

" These problems are also expected to lead to tighter financial conditions, which would be an additional headwind for the global economy," he said.

ABC/Reuters