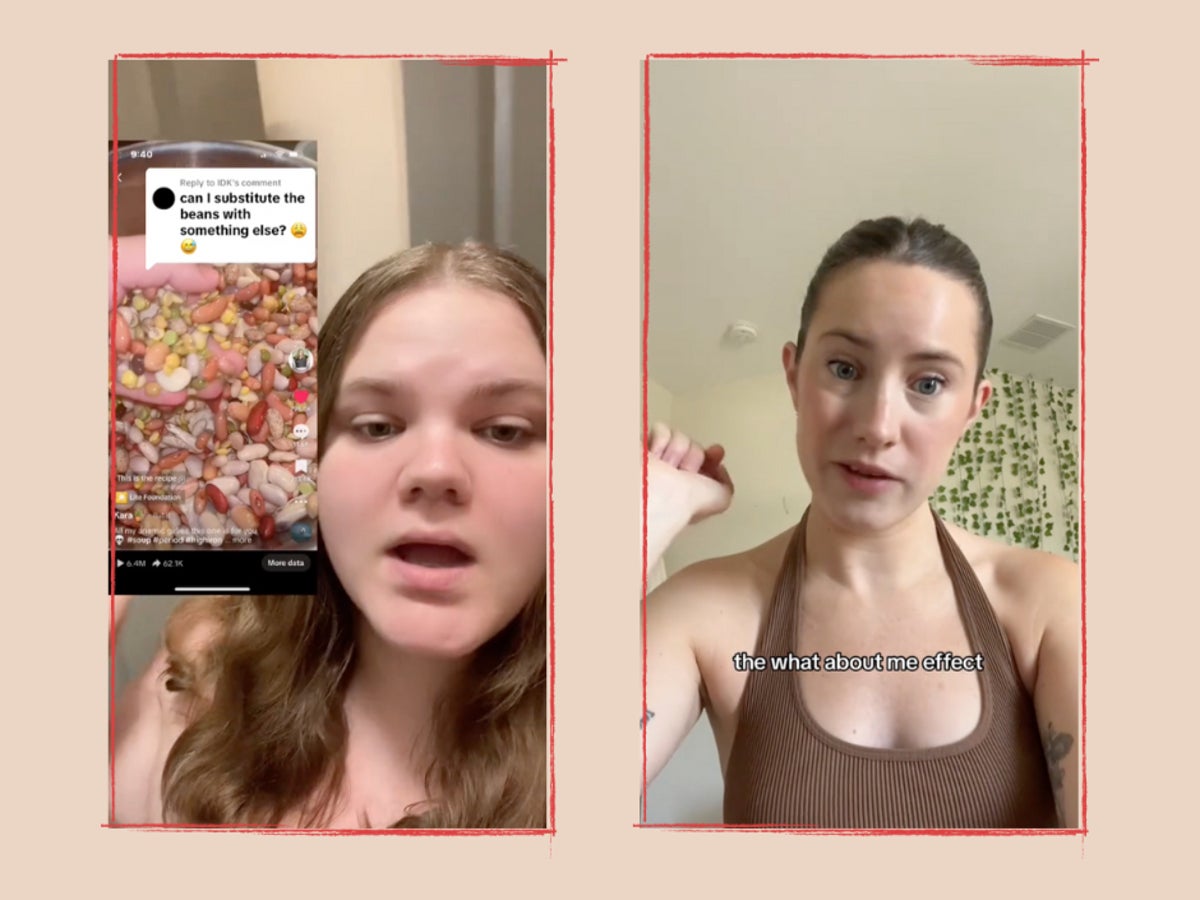

Sarah Lockwood was scrolling on TikTok one morning when she came across a video for bean soup. The vegan recipe - which, you guessed it, contained beans - promised to be a healthy way for women to up their iron intake during menstruation. While the recipe was straightforward, and seemed to be catered to a very specific group of people, a number of comments under the video asked whether they could replace the beans in the bean soup video for another ingredient. “Can I substitute the beans with something else?” wrote one TikTok user.

This wasn’t the first time Lockwood, who is a 26-year-old lifestyle coach and content creator living in New York and New Jersey, had seen comments like this before. Another video for a strawberry milk recipe had someone else wondering if they could still drink the milk, even though they were allergic to strawberries. Enough was enough for Lockwood, and she took to the platform to make her own video describing these remarks as “what about me?” comments.

“I wanna talk to you guys about something I’ve decided to call the What About Me effect,” Lockwood said in her video, which has been viewed more than four million times since it was posted on 14 September. The newly-dubbed What About Me effect, Lockwood explained, described the phenomenon of when a video or topic “doesn’t really pertain” to someone’s lifestyle or interests, but they somehow “find a way to make it about them”.

“The What About Me effect basically combines individualistic culture with being chronically online, and it is rampant on TikTok,” she said. Lockwood ranted to her 70,000 TikTok followers about her frustration when she came across the bean soup video, and the barrage of commenters asking for recipe substitutions.

“Instead of just saying: ‘Hey, if I don’t like beans maybe I shouldn’t watch this bean soup video,’” Lockwood said. “We make everything about ourselves and seek out accommodations and validation for everything.”

The What About Me effect soon took off, as content creators were finally able to put a name to the annoying and irritating responses they receive from unintentional social media trolls. As a content creator for the past three years, Lockwood said she became aware of the What About Me effect because she too saw it happening under her own videos.

“I’m sure other creators can relate to this, because we do get comments all the time like: ‘Well, what about my specific situation?’” she tells The Independent. “I’m like, what about it? Maybe this video is just not for you. Maybe you’re just not the target audience for it. The What About Me effect kind of came out of receiving those types of comments, and then it just popped into my head.”

TikTok - a social media app that launched in 2016 - has grown in popularity for its bite-sized clips and platform-specific trends. Unlike Instagram, where real-life celebrities also dominate feeds, everyday users on TikTok can become influencers simply by being themselves.

TikTok’s approachability is also why the app blew up in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic. As millions of people around the world were forced to quarantine indoors, TikTok emerged as a space where people could escape the mundane and “romanticise” their lives. The hashtag #RomanticizeYourLife even encouraged users to find beauty in their everyday routines, whether it was making avocado toast for breakfast or redecorating your bathroom. Internet users quickly became the main character in their own lives, taking control of the narrative in a world that increasingly lacked control. But out of the “main character energy” trend came its irritating little sibling, main character syndrome - perhaps the foundation for the What About Me Effect we see today.

Main character syndrome describes a tendency among people to view themselves as the lead character in their own life story, and in the lives of those around them. But unlike main character energy, those with main character syndrome can be self-centered and self-absorbed. It’s neither diagnosable nor a clinical term, and shouldn’t be confused with narcissistic personality disorder, which affects just one per cent of the population.

“Main character energy is when you’re going through life, whether it’s scrolling on the internet or literally walking through your life, and you’re experiencing how everything is affecting you and relating to you,” Jeff Guenther - a licensed professional counselor and a mental health therapist with 2.8 million followers on TikTok under the username @TherapyJeff - tells The Independent. However, problems arise when the “main character” of their own life begins to only see the world from their point of view, and slips into main character syndrome.

“When we talk about some of the negatives, the energy part slides more seriously into the syndrome,” says Katherine Glaser, a licensed clinical social worker with Thriveworks who specialises in self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. “When they fictionalise themselves as they’re needing validation from others, it gets a little bit out of control. They start to see themselves almost like a protagonist, almost like they are this main character in the movie of their own life. These folks tend to be kind of self-absorbed, they think about themselves most of the time. It’s almost like they see other people that are in their life as supporting roles. This sense of entitlement can get them in trouble in certain social situations.”

While main character syndrome does indeed tend to go out of control, it’s the behaviours of main character syndrome - such as centering oneself - that are sometimes adopted in response to a lack of control in the first place. Glaser, who’s been in practice for 20 years as a licensed clinical social worker, often works with adolescents and young adults who’ve endured “bad experiences with social peers” in the past. When her patients express a desire for a fresh start, Glaser noted that they too can tap into their main character energy, so as to “recreate themselves” and “increase their own self-worth”.

“Usually, there’s some lack of feeling in control of their life for whatever reason, and this is a way of grasping at some kind of control,” she says.

In a world that seems to be lacking control on all cylinders - ongoing conflict over militarised land, politicians ousted of positions by their own party, and disputes over artificial intelligence affecting the entertainment industry - one would argue that becoming the main character in your own life is actually an emotionally mature way to compartmentalise it all. Why shouldn’t you be the main character in your own life? It’s your life after all. Even on apps like TikTok, algorithms are built for us to assume the role of the main character when content feeds are literally called the “For You Page”.

“One might assume that all the content that is being delivered to them by Daddy Algorithm is specifically for them,” says Guenther. “When something comes across their page and it doesn’t resonate with who they are, them being the main character of their life, that’s just how the ego operates - our psychological ego. We all have an ego and we’re looking through this very specific lens that we’ve created, or has been influenced by all the things that we’ve grown up around, and that’s how we interpret reality, by centering ourselves in everything. That can be very problematic.”

Sure, adapting some main character energies may be well and good. For starters, making yourself the main character can be beneficial in relationships - allowing yourself to be selfish in order to let a partner or close friend know exactly what your needs are and how you will feel fulfilled. Main character syndrome can also help others be more assertive, go after their goals, and be emotionally aware of their surroundings.

In fact, according to Guenther, it’s even developmentally appropriate to experience main character energy into adulthood. “It’s a very important developmental stage to go through… and then to exit,” he said. The problem, though, is that there’s some of us who don’t exit this stage.

In October 2022, a woman named Daisey Beaton unexpectedly found herself at the centre of controversy when she described on X - formerly known as Twitter - the sweet morning routine she shares with her husband. “My husband and I wake up every morning and bring our coffee out to our garden and sit and talk for hours,” posted the 24-year-old, who owns a beauty company called The Wholistic Esthetician. “Every morning. It never gets old and we never run out of things to talk [about]. Love him so much.”

What was a poignant anecdote about her relationship with her husband soon received backlash from hundreds of users accusing her of being inconsiderate, wealthy, and “privileged” to even have a garden in which she can enjoy coffee with her husband.

“Don’t you guys go to work?” replied one user, while another said: “Sounds like you and your husband need to get jobs.”

“What was the purpose of this post except to make me feel terrible about myself?” another person wrote.

Before there was the bean soup video, there was the coffee in the garden tweet. The What About Me effect caused a barrage of people to assume Beaton and her husband don’t have jobs (she teaches yoga and he’s a professional skateboarder), and to offer up why their lives were 10 times worse.

“That’s cool. I wake up every morning and fight my way through traffic for an hour in Miami to get to work. Must be nice,” one person wrote. “I wake up at 6am, shower and go to work for a shift that is a minimum of 10 hours long. This is an unattainable goal for most people,” another said.

According to Dr Justin Puder, a licensed psychologist in South Florida with 683,00 followers on TikTok, it’s so enticing for some to leave What About Me comments online because each one comes with a validational reward. “We do this because we gain from it. We get a dopamine hit every time our contrarian comment gets likes or somebody else commenting underneath,” he says. “They’re like: ‘I also hate beans.’ There’s utility in doing this. As a creator, it’s annoying! But I also know why it exists. They gain something from doing this.”

In her video, Lockwood hypothesised that the What About Me phenomenon occurs in an “individualistic culture combined with being chronically online”. Perhaps it isn’t validation in the form of a like that the What About Me effect is seeking, but rather some recognition in a society where hyperindividualism prevails.

“A lot of people write this off as a lack of common sense, which it can be, but I see it as almost a larger issue. In my experience growing up in the United States, seeing this individualistic culture we have, everything’s about me. There’s this kind of egocentric culture where we think that everything has to be for us,” Lockwood says. “We have to insert ourselves in everything when we see something online. We almost get upset if the person isn’t speaking about a universal experience, like: ‘How dare you share something I can’t relate to?’”

We run into danger, though, when each What About Me comment detracts from important conversations at hand. When it comes to diversity, equity and inclusion, it goes without saying that a recipe video for bean soup isn’t necessarily taking away power from those who prefer not to eat beans. But for so-called “chronically online” users leaving What About Me-type comments on social media, Lockwood believes their supposed concern for others - ie, those who can’t eat beans - is only masquerading as a fight for inclusivity.

“There are real important conversations about inclusivity, but do we really need to make sure we’re being inclusive of people who don’t like beans? This is a ripple effect of the What About Me effect, that comments are very trivial and make a mockery of real conversations for inclusion and really important conversations about equity,” she says. “Those types of comments are weaponised to make sure that people who are discussing real arguments for inclusivity are not heard or are not taken seriously.”

Still, Lockwood has proposed some resolution to the What About Me effect that’s fuelling main character syndrome. “As individuals, it’s really important for us to be cultivating more self-awareness,” she says. “On an individual level, it is our responsibility to cultivate our own self-awareness, self reflect, ask yourself: ‘Why do I feel the need to comment about this video and make it about me? Why do I feel the need to shame a creator for posting something that I can’t relate to?’

“Not every single thing that we see is going to be relatable to us, and that’s okay. It doesn’t have to be. It doesn’t mean that someone has done something wrong by doing something you can’t relate to.”