Today the US celebrates 246 years of independence from colonial British rule, the end of the Revolutionary War and the day a global superpower was born.

Millions of Americans will gather to enjoy fireworks, parades, picnics and barbecues with their loved ones, an occasion free of coronavirus restrictions for the first time since 2019.

To mark the occasion, we look back at the history of the Fourth of July and the men who made it all possible.

America lost its second and third presidents on the same day

Three US presidents have died on 4 July, all Founding Fathers and two on the same day: 4 July 1826, the 50th anniversary of the country’s foundation.

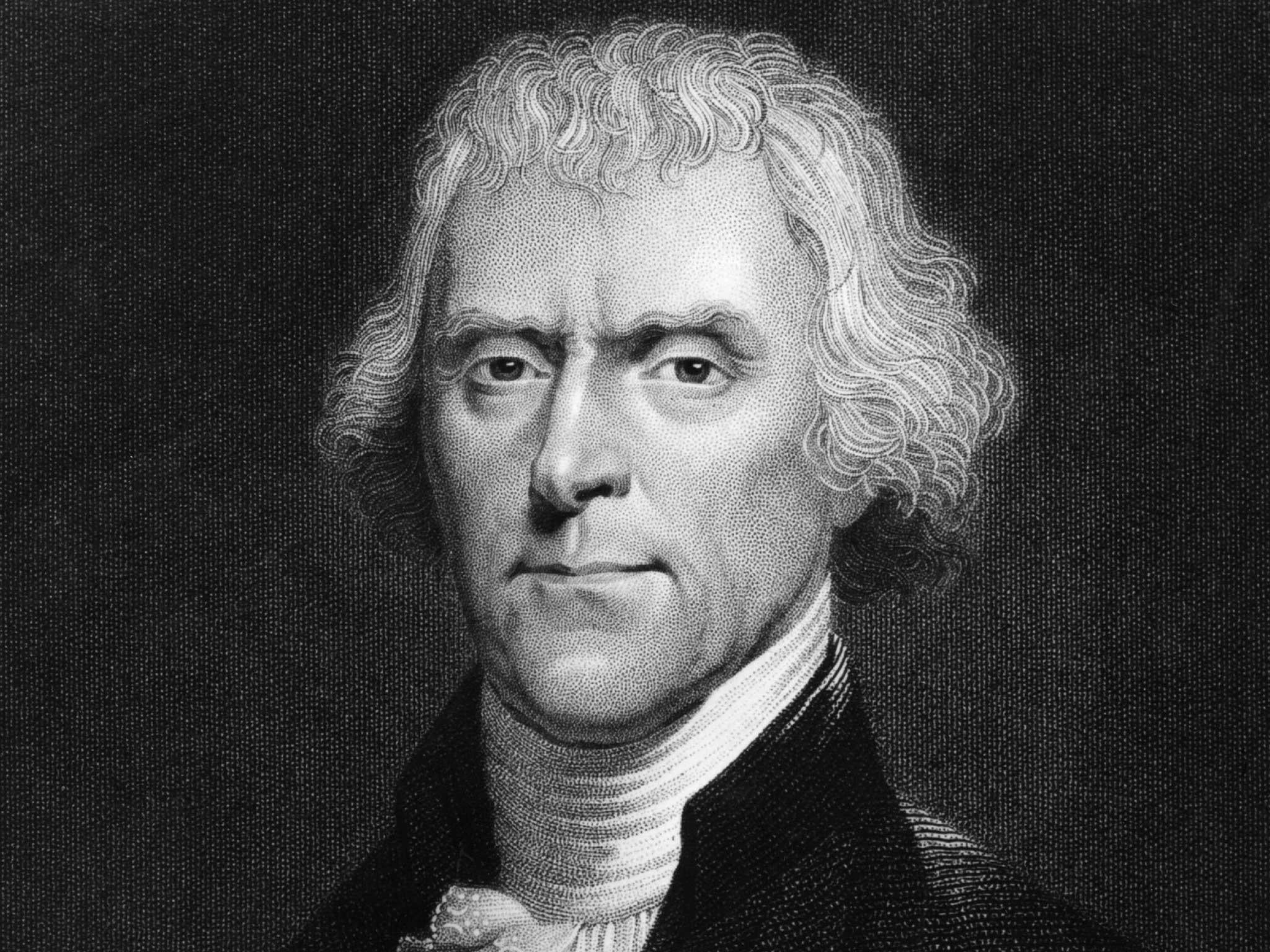

Thomas Jefferson’s later years were riddled with ill health and debt. The third president died at home in Virginia, aged 83, surrounded by his family.

That same day, John Adams, who had succeeded George Washington and masterminded the Declaration of Independence, also passed away at home in Quincy, Massachusetts, aged 85.

Tragically, Adams consoled himself with the final words “Thomas Jefferson survives”, the statesman mercifully unaware that his friend and fellow nation-builder had himself expired just hours earlier.

These men would be joined by the fifth president, James Monroe, who died on 4 July 1831. The Adams legacy lived on, however. John's son, John Quincy Adams, served as the sixth.

The Boston Tea Party and a fight for freedom

American independence was the product of years of souring relations with Great Britain, as the citizens of the Thirteen American Colonies grew increasingly frustrated with Parliamentary rule from across the Atlantic and the notion of "taxation without representation".

Discontent began brewing in 1763 as the House of Commons introduced measures to increase revenue from its imperial subjects, with the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767 sparking particular anger across the pond.

Matters came to a head with the Boston Tea Party in 1773, when a political protest group known as the Sons of Liberty dressed as Native Americans and dumped an entire shipment of British tea leaves imported by the East India Company into the harbour. The demonstration was both a gleeful satire of the ruling power’s obsession with its national beverage and a call to arms against the decadence and entitlement of empire.

The bloody War of Independence broke out in earnest two years later.

The signing of the Declaration of Independence

A year into the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, delegates from the Thirteen Colonies gathered to compose a statement formally declaring their sovereignty from London.

Known as the Second Continental Congress, the meeting saw the leaders come together at the Pennsylvanian State House in Philadelphia to sign a document that would both renounce British imperial control and introduce a new nation: the United States of America.

Drafted by the Committee of Five – John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston – the document established citizens’ "unalienable" rights, observing that "all men are created equal" and enshrining the individual’s entitlement to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness".

The draft was submitted to Congress on 28 June 1776, voted into law on 2 July and formally ratified on 4 July, a date that has been celebrated by patriotic Americans ever since.

Among the most famous statesmen to sign the declaration was John Hancock, whose name lives on as a synonym for signature, as well as Adams and Jefferson, both then future presidents in waiting.

Benjamin Franklin: Enlightenment polymath

While the Founding Fathers were all men of grand vision, none was more so than Benjamin Franklin.

Later celebrated as “the First American”, Franklin embodied the Puritan work ethic of the 18th century, serving as political campaigner, diplomat, ambassador to France, postmaster-general and newspaper publisher while still finding time to dabble in freemasonry, music, chess and scientific experimentation. It is in this final capacity that he is best remembered outside of the political sphere today.

Franklin first experimented with electricity in 1746 and successfully trapped lightning by flying a kite in a storm from a Philadelphia hillside in 1752, therein establishing both the principle of battery storage and the lightning rod.

Franklin’s other inventions included bifocal glasses, a metal-lined cooking stove and a flexible urinary catheter. Truly a remarkable man.

Thomas Jefferson’s not-so-secret mistress

Although hailed as the author of independence, Jefferson was no saint.

The third president of the United States kept slaves, among them Sally Hemings (1773-1835), a mixed-race servant girl whose six children Jefferson is widely believed to have fathered following the death of his wife Martha in 1782.

A DNA study in 1998 established a direct genetic link between the revered politician and Eston Hemings, Sally’s youngest son.

Hemings lived and worked on Jefferson’s Monticello plantation home in Charlottesville, Virginia, and travelled with him to Paris, where their relationship is thought to have first been consummated.

The affair was controversial at the time and used to discredit Jefferson by political journalist James T Callender, though the president himself never confirmed or denied it.

Hemings’ four surviving teenage children were released from slavery upon Jefferson’s death as stipulated in his will, as was Sally herself, who lived the final nine years of her life as a free woman, residing near Monticello with her two sons until her death.