The Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF), which has governed Zimbabwe since independence in 1980, is well known for denouncing the United States’ role as a superpower that polices the world.

In a 2007 address at the United Nations, then Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe assailed his American counterpart, George W. Bush. Mugabe charged:

his hands drip with innocent blood of many nationalities. He kills in Iraq. He kills in Afghanistan. And this is supposed to be our master on human rights?

Confrontation with the US, a recurrent feature of Zimbabwe’s political history since the 1960s, surged after Washington adopted a bipartisan sanctions package in 2001. The European Union also imposed sanctions.

US officials have repeatedly stated that the sanctions target specific individuals or entities that have abused human rights or undermined democracy. Zanu-PF has responded by pointing to UN reporting which notes that the sanctions have weakened the country’s economy and impeded national development.

I am a historian of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle. My forthcoming book focuses on its formative stages in the late 1950s and early 1960s. This was when Mugabe first became active in politics and the US got more involved in the politics of what was then Rhodesia, a British colony. In my view, the 21st century hostility obscures a nuanced historical relationship between the US and Zanu-PF.

Read more: Winky D is being targeted by police in Zimbabwe – why the music star's voice is so important

At first, the fledgling liberation movement valued American support. Zanu-PF broke away from the Soviet-aligned Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu) in August 1963. Zanu-PF was originally known as Zanu, but adopted the “PF” suffix ahead of elections in 1980.

This context is relevant now because Zanu-PF efforts to consolidate both domestic and pan-African support selectively overlook more compatible aspects of its historical relations with the US.

Zanu-PF’s anti-American bluster

Zanu-PF has exploited sanctions to its advantage.

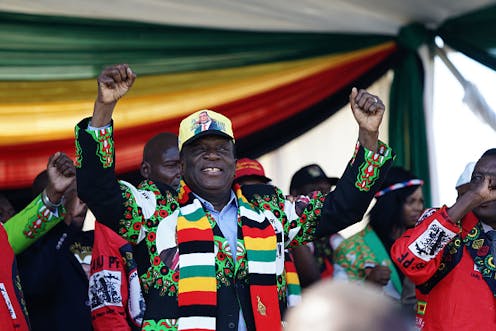

Emmerson Mnangagwa, previously Mugabe’s deputy, came to power in a factional coup in late 2017. He has successfully mobilised pan-African support against sanctions.

Since 2019, the Southern African Development Community and the African Union have observed 25 October as “Anti-Sanctions Day” in solidarity with the Zanu-PF leadership.

Zanu-PF’s anti-American rhetoric is not only deployed to win friends abroad. It is also a prominent campaign tactic at home.

Read more: President Mnangagwa claimed Zimbabwe was open for business. What's gone wrong

With general elections expected in July or August, Zanu-PF is following the strategy again. It’s discrediting its leading opponent, Nelson Chamisa of the Citizens Coalition for Change, as a “US pawn”.

His predecessor, Morgan Tsvangirai, faced similar treatment.

Zimbabwe’s partisan state media routinely employ such terms as “puppets”, “pawns” and “lackeys” to describe Chamisa and his party. These jibes are intended to convince Zimbabwean voters that Chamisa would prioritise foreign interests.

The rhetoric conceals ZANU-PF’s own American ties.

Zanu-PF’s American connections

Historically, relations between the US and Zanu-PF have fluctuated. Mugabe formed a close bond with Andrew Young, the US ambassador to the UN during Jimmy Carter’s presidency. Carter’s government was the first to open an embassy in independent Zimbabwe.

Solid relations continued during the early years of the Reagan administration. Harare was one of the top three African recipients of US aid in the early 1980s.

US vice-president George H.W. Bush travelled to Harare in 1982. In 1997, first lady Hillary Clinton made a goodwill visit to Zimbabwe.

Ties were even deeper in the early 1960s when the US government encouraged the party’s very establishment. Historian Timothy Scarnecchia, who has mined records in the US national archives, has documented the ties that Zanu forged with American officials 60 years ago.

Read more: Repression and dialogue in Zimbabwe: twin strategies that aren't working

The organisation’s core leadership in temporary exile in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (then Tanganyika), regularly consulted with US embassy officials in that country. Its leading representatives, including Mugabe, lobbied the US government for funding. (There is no evidence that the new party received any directly.)

Zanu’s first president, Ndabaningi Sithole, received theological education in the US in the late 1950s. Archival records show that on the eve of Zanu’s formation he met with State Department officials in Washington DC who connected him to private American funders. In another archived account of a meeting with the US ambassador in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) in July 1963, Leopold Takawira, subsequently Zanu’s first vice-president, relayed that Sithole regarded the US as his second home.

Herbert Chitepo, who became Zanu’s national chair, visited the US in July 1963 and also met with American diplomats. According to a record of their conversation in the US national archives, Chitepo expressed his desire to accept US funding and defied

anyone to call him an American stooge.

The 11 July 1963 issue of Zimbabwe Today, a periodical produced by Zapu in Tanzania, declared that following Sithole’s return from the US,

the American dollar and its ugly imperialist head is clearly visible in the actions of Mr. Sithole.

Zanu-PF’s assaults on Chamisa and his party’s supposed American connections is a repackaging of the very attacks Mnangagwa’s party faced from Zapu when it was formed 60 years ago.

Double standards

Although it has not been well documented, the US provided critical support during Zanu’s founding in 1963. It also helped the party consolidate its authority following independence in 1980. Since the US government imposed sanctions on Zimbabwe in 2001, these ties have been overshadowed.

Read more: Can Zimbabwe finally ditch a history of violence and media repression?

As elections approach in Zimbabwe, the role of the US looms large. Zanu-PF overlooks historical aspects of its own relations with the US as it seeks to undermine its domestic opposition and appeal to continental allies.

Brooks Marmon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.