Vladimir Putin's ongoing failure in Ukraine has put his strategic alliance with Chinese President Xi Jinping to the test. With Mr Putin growing ever more desperate, Mr Xi must finally realise the scale of the threat that his "friendship without limits" with the Russian president poses to China's economic health, to global stability, and to his own geopolitical ambitions.

While Mr Putin may or may not have been bluffing when he threatened to use tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine last month, Mr Xi must assume the worst if he wants to be viewed as a responsible leader. After all, Russia's military doctrine allows for a nuclear strike to defend Russian territory against an existential threat. Russia's illegal annexation of the occupied Ukrainian regions of Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia provides the pretext for such an attack.

Mr Xi, who is expected to secure an unprecedented third consecutive term as China's leader at the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China later this month, must now turn his attention to preventing World War III. A Russian nuclear strike in Ukraine -- the first use of such weapons since the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 -- would ignite a catastrophic global crisis, spoiling Mr Xi's coronation.

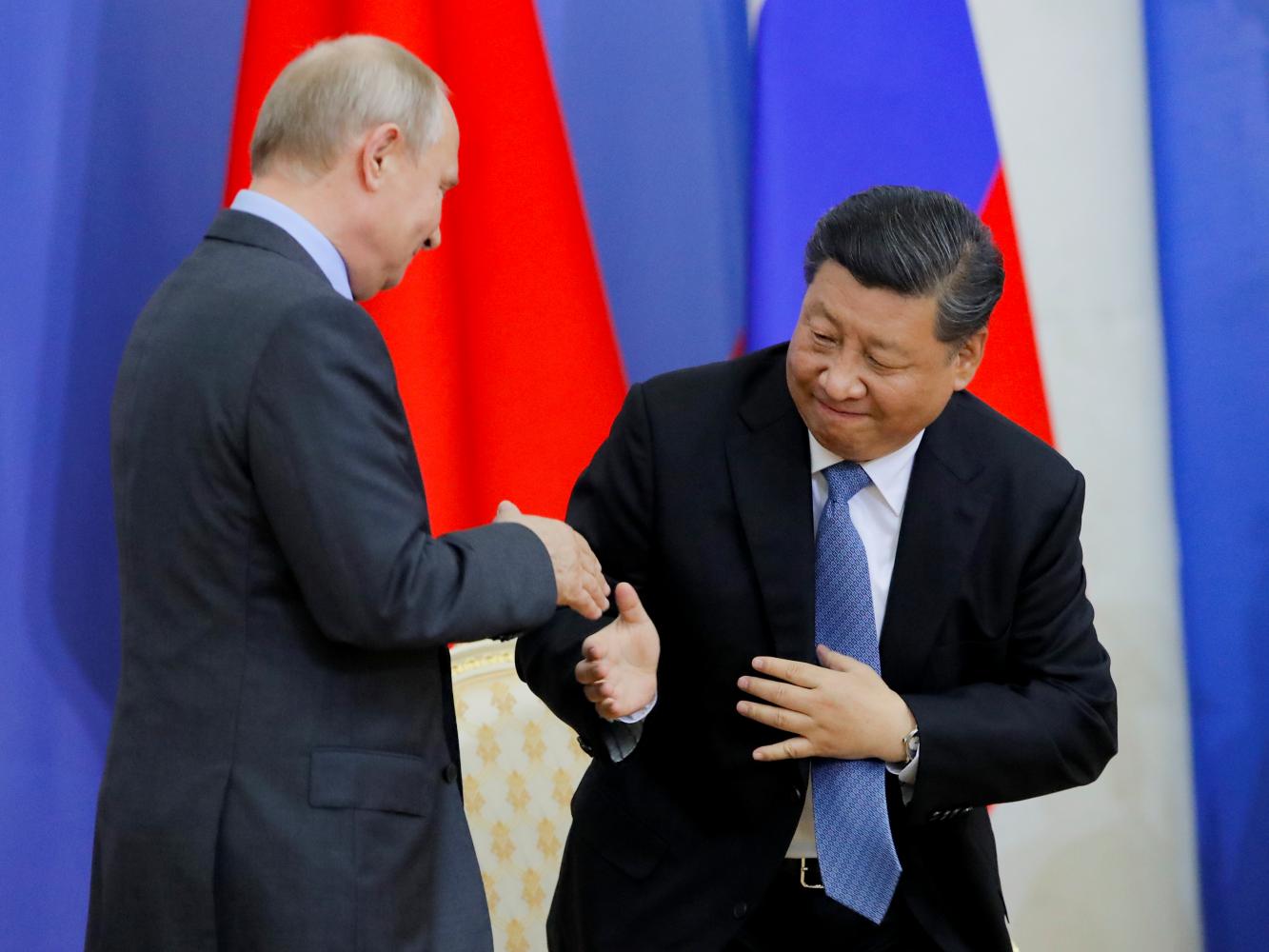

When Mr Xi and Mr Putin met at the Beijing Winter Olympics in February to sign the Sino-Russian cooperation agreement, the plan to invade Ukraine must have seemed like a safe bet: the Russians would quickly topple Ukraine's leadership, which would make the US and Nato appear weak. A proxy war would also divert US attention from its rivalry with China -- or so Mr Xi thought.

Then Ukraine fought back, exposing Russia's myriad military weaknesses. Russian forces have now retreated from the Kharkiv region in the northeast, following Ukraine's impressive counter-offensive, and are suffering heavy losses near Kherson in the south. Mr Xi almost certainly conveyed his displeasure with Russia's failures when he met Mr Putin at the recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization Summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

Mr Putin publicly acknowledged China's "questions and concerns" about the war (a rare admission of tensions between the two countries) while Mr Xi himself did not mention Ukraine at all. Mr Xi's silence stood in stark contrast to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who, in a remarkable volte-face, openly rebuked Mr Putin.

Still, it is hard to believe that Mr Xi is not wondering whether he made the right decision when he tied his political fate to so reckless an ally. Mr Putin's "partial mobilisation" of 300,000 Russian men to join the fight in Ukraine has triggered protests across Russia and caused more than 200,000 young men to flee the country. The quality of Mr Putin's new recruits, who include convicts, is unlikely to help the war effort or assuage Mr Xi's concerns.

With morale among Russian troops already at rock bottom, an infusion of dispirited and ill-trained draftees may hasten the dissolution of Mr Putin's military and the fall of his regime, akin to how Czar Nicholas II's poor leadership during World War I fuelled the collapse of the Czar's armies and the Russian Revolution of 1917. With his direct appeals to Russian soldiers to surrender or die, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky seems to understand the perilous state of the Russian military better than Mr Putin does.

The point of a proxy war is to weaken one's adversary, but Mr Putin's incompetence has achieved the exact opposite for Mr Xi. Nato is now stronger than it has been at any point since the Cold War's end, with previously neutral countries like Sweden and Finland applying to join and Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, and increasingly India voicing support for America's Ukraine policy. Instead of helping China to establish itself as a counterweight to US global hegemony, Russia has been exposed as too weak and corrupt to defeat even a middling country. With Mr Putin now issuing direct orders to Russian field commanders, China's military alliance with Russia must seem almost worthless to Mr Xi.

While the chances of Mr Putin using a nuclear weapon in Ukraine appear slim, they cannot be fully discounted. So, Chinese officials must be trying to assess how the US and Nato would respond if Mr Putin followed through on his threat. Given US President Joe Biden's tough-minded if still ambiguous statements, it is safe to assume the international economic and military response would be far more severe than the sanctions already imposed on Russia.

But if Mr Putin does decide to use a tactical nuclear device to "defend" the Ukrainian territory that he has illegally annexed, he may well open a Pandora's Box of horrors. For example, his war has brought considerable chaos to Ukraine's nuclear power stations, and, in addition to other concerns about their operation, it can no longer be assumed that their spent nuclear fuel rods have always been safely secured during the battles for control of the sites. This opens the terrifying prospect of some mad partisan creating a "dirty" bomb to use in retaliation.

Mr Putin's annexations may also undermine the "One China" policy regarding Taiwan. Some Eastern European countries are already voicing doubts about the wisdom of that policy. If Mr Xi, who has defended the principle of territorial integrity, silently accepts Mr Putin's annexations, some countries may decide that Mr Xi's hypocrisy has nullified the "One China" policy.

Ever since he became president 10 years ago, Mr Xi has signalled his fear that China could suffer the type of disintegration that led to the implosion of the Soviet Union. Mr Putin's current predicament should serve as another cautionary tale. The prospect of a regime so rotten that it collapses from within must haunt China's president almost as much as the threat of nuclear war. ©2022 Project Syndicate

Charles Tannock, a former member of the European Parliament Foreign Affairs Committee, is a fellow at GLOBSEC, a think tank based in Bratislava.