The relationship between art and life is tricky to navigate. But in the case of the Polish-born Australian artist Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz (1918-1999) the two seem inseparable. This is evident in the outstanding commemorative solo exhibition of his artistic career, Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz: 100th Anniversary Exhibition, expertly curated by his son Adam and currently on show at South Australia’s elegant Murray Bridge Regional Gallery.

Born in Stara Sol, near Lwow, Wlad (as he became universally known) studied visual art, initially at the Krakow Academy. Later, he studied drama at the Drama Academy of the Polish National Theatre in Lwow. Following this, he travelled to Paris to further his visual arts studies at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts.

At the outbreak of the second world war in 1939, Wlad Dutkiewicz, at just 21, held the position of assistant director of the National Theatre in Lwow. As the war ripped through Europe, Poland was hit especially hard. The Nazis specifically targeted Poles of Jewish faith.

Young Wlad joined the Polish Resistance, helping Jews to escape and risking his life in other ways. On August 24, 1944, now 26, he was captured by the Nazis and transported to Auschwitz where he stayed for a short time. Then Dutkiewicz was sent to a German labour camp, but was eventually relocated to Reisen Gebirgen, escaping only when he heard of Hitler’s death. After walking and hitching to Prague he was given papers by the Resistance, enabling his safe passage thereafter.

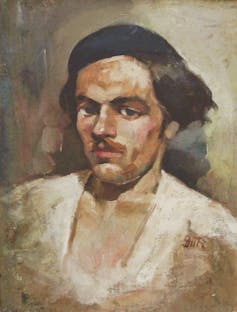

Adam Dutkiewicz, a visual arts writer and critic, has displayed the artworks in roughly chronological order. The exhibition begins with Wlad’s only self-portrait, painted in 1945 when he was interned in a displaced persons camp in Allied Germany. While it’s a sombre work, imbued with tough white-knuckle poetry, there’s no hint of self-pity.

1949: migration to Australia

August 24 was to become a red-letter day in Wlad’s life. In 1949, on August 24, precisely five years after his escape from the German POW camp, Wlad arrived in Western Australia as a refugee.

Ironically, on moving to Adelaide, Wlad first found employment as a painter – of sorts. The task was to repaint Adelaide Railway Station, bedecked at that time with Art Deco livery. The paint selected for its platforms, roofs and pillars was vivid blue. Later Wlad was to refer to this as his “blue period” – jocularly referencing Picasso’s nomenclature for his earliest group of artworks.

In 1951, Wlad held his first exhibition in Adelaide. As part of a larger and celebrated group of displaced Eastern European artists, including his brother Ludwik, brothers Dusan and Voitre Marek, Ieva Pocius, Stanislaus Rapotec and Alex Sadlo, and with Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski joining them later, Wlad’s status grew.

Like the Cubists, they formed an artistic movement. The Adelaide Art Gallery director, Daniel Thomas, termed this émigré group “Slavic Space Age” artists – and into orbit they went.

In 1953, Wlad married Joan Watson, an Adelaide woman. They had five children in rapid succession: Michal, Adam, Ursula (an artist now based in Melbourne), Anna and Cecilia.

Reception in the art world

It’s possible to interpret these works in various ways. Thematically, by comparison with the works of many other post-WW2 European artists, one thing clearly stands out – what Wlad’s paintings aren’t about. Dutkiewicz’s artworks are not permeated with violence, despair or obvious post-war angst, except obliquely. His intention seemed to be to build a new life in a new country.

By the same token, when Dutkiewicz arrived in Australia, he brought with him a more artistically sophisticated, European–based sensibility and level of artistic education that exceeded the norm in this country at the time. (Wlad’s knowledge base obviously excluded the complex Aboriginal traditions that had been in place for eons, although he visited several Aboriginal settlements in WA in a quest for greater understanding).

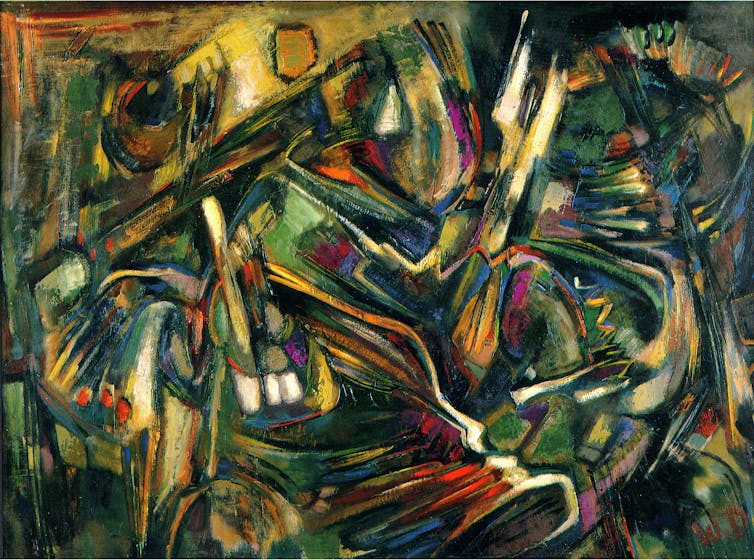

In his magisterial For Stravinsky, it’s apparent that Dutkiewicz maintained his passion for not only the visual arts but also for theatre and music. (He also directed and acted in plays in Adelaide theatres.)

Dramatised by his theatrical deployment of colour, form and line, Wlad’s modernist, apparently abstract compositions, including Vibrato and In Orbit, attest to this. While Petrushka’s spiky visual texture has been created with an unusually restricted palette, its geometric, quasi-figural shapes seem constrained by an insuperable spatial or psychological barrier. There’s a sense that these and all of his other artworks are underpinned by a narrative or performative subtext of some kind, but also by the elaborate time/space theory that he’d developed in relation to his art making.

Akin to the early European response to the deliberate dissonance and flouting of established conventions of tonality in Stravinsky’s musical compositions (one Parisian critic described his Rite of Spring as an “open sewer”), the reception of Dutkiewicz’s works and those of his compatriots divided Australian opinion.

While the staid Adelaide folk of that time did not so openly express their disgust at the chaos and energy that characterised Dutkiewicz’s artworks, the detractors were many. Yet Wlad also had his early champions – notably the writer Max Harris, of Angry Penguins fame (and notoriety), who publicly stated that Dutkiewicz’s artworks were the equal of those of Sidney Nolan and Russell Drysdale.

A number of Dutkiewicz’s works make reference to the Australian environment – for example, his electrifying rendition of the Blue Lake near Mt Gambier.

Wlad also made artworks about people engaging in everyday activities: for example, his Bathers, and Fishing. Other works feature family members, including his loving depiction of his oldest daughter as a young child in the figural work Ursula’s Toy.

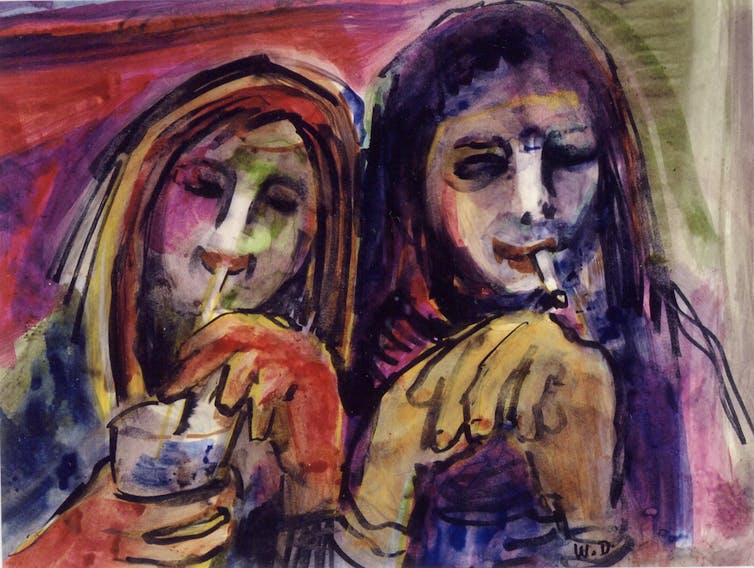

There is also a category of work based on social commentary – for instance, his Beatniks, ordinary teenagers mostly reviled by Australians at the time. Perhaps Wlad championed these outlier youths because he himself lived a bohemian life (or as bohemian as a parent with five young kids could be).

And finally there’s Wlad’s sheer technical skill as an artist. Every one of his artworks is finely wrought, highly disciplined and technically perfect.

Wlad Dutkiewicz needs to be remembered as a pivotal figure in Australian art history, making this a truly significant exhibition. It is hoped that it will contribute to expanding the cultural memory and the Australian national imaginary.

Wladyslaw Dutkiewicz: 100th anniversary exhibition is at the Murray Bridge Regional Gallery until June 10, 2018.

The author would like to acknowledge Adam Dutkiewicz and Melinda Rankin, curator and CEO of the Murray Bridge Regional Gallery, for assistance with this article. This exhibition is part of South Australia’s History Month.

Christine Judith Nicholls does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.