The pandemic has given Americans ample reason to be skeptical of pronouncements by the Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC). A press release the CDC issued today reminds us that the agency's habit of misleading the public began long before anyone had heard of COVID-19.

According to the latest results from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), the CDC says, "about 2.55 million U.S. middle and high school students reported current (past 30-day) use of a tobacco product in 2021." If you have not been paying attention to the CDC's inveterate dishonesty on this subject, it may surprise you to learn that most of those 2.55 million students did not use products that contained tobacco.

The CDC routinely conflates e-cigarettes with "tobacco products," despite the vast difference between the risks posed by vaping nicotine and the risks posed by inhaling smoke from conventional cigarettes. The press release notes that "about 1 in 3" of those 2.55 million students "used at least one type of combustible tobacco product," which means two-thirds did not. The CDC says 410,000 of the past-month "tobacco product" users, or just 16 percent, were cigarette smokers. But the CDC implies that such distinctions don't really matter, because "youth use of tobacco products is unsafe in any form—combustible, smokeless, or electronic."

The CDC, which claims to follow the science and deliver its findings to Americans who don't have time to read and digest the relevant research, is deliberately obscuring the medically crucial point that e-cigarettes are far less hazardous than the conventional, combustible kind. Statements like this one help explain why a large and growing share of the public mistakenly believes that vaping is just as dangerous as smoking, if not more so.

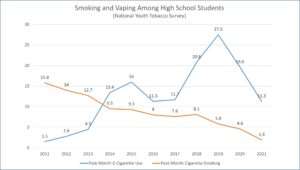

Here is something else that may surprise you, since the CDC is determined to ignore it: Smoking among teenagers has been falling since the late 1990s, and that downward trend accelerated as vaping took off. The replacement of smoking by vaping is indisputably an improvement in terms of "public health," which the CDC claims to be promoting. But the agency instead portrays it as a grave danger to the youth of America.

In the 2021 NYTS, less than 2 percent of high school students reported that they had smoked cigarettes in the previous month, down from 4.6 percent in 2020, 8.1 percent in 2018, and 15.8 percent in 2011. The CDC completely overlooks this good news, because it undermines the agency's attempt to gin up public alarm about "tobacco use" by teenagers.

The NYTS measured a sharp increase in past-month e-cigarette use by high school students between 2017 and 2019, which led to many warnings about the "epidemic" of underage vaping. But that rate, which peaked at 27.5 percent, fell to less than 20 percent in 2020 and about 11 percent in 2021.

The CDC warns that the 2021 numbers "cannot be compared with results from previous NYTS surveys," which "were primarily conducted on school campuses." Due to the pandemic, the 2021 survey was "administered online to allow eligible students to complete the survey at home, school, or somewhere else." Half of the students took the survey at school, while the other half took it at home or elsewhere. Although "we remain confident in our study results," the CDC says, "the reporting of tobacco use might differ by the setting where the survey was completed."

The CDC can't have it both ways. If the 2021 survey presents an accurate picture of "tobacco use" by middle and high school students, which the CDC says it does, any bias created by the change in methodology must not be very important.

"Differences in tobacco product use by survey completion setting might be caused by potential underreporting of behaviors, reduced access to tobacco products while at home, or other unmeasured characteristics among students participating outside of the classroom," says the CDC's NYTS report, which was published today in the agency's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The CDC seems to be suggesting that students who completed the survey at home may have been less honest than students who completed it in school. While that's possible, it is also plausible that the enhanced sense of privacy at home increased candor.

In any case, the CDC's report on the e-cigarette results, which it published last September, notes that "15.0% of high school students who took the survey in a school building or classroom reported currently using e-cigarettes," which is still 23 percent lower than the rate in 2020 (19.6 percent) and 45 percent lower than the rate in 2019 (27.5 percent). The report did not acknowledge that downward trend. Here is how the headline summed up the survey results: "Youth E-Cigarette Use Remains Serious Public Health Concern Amid COVID-19 Pandemic."

Today's report notes that the overall rate of "current tobacco product use" among students who took the survey at school was 11.7 percent, which is down from 16.2 percent in 2020 and 23 percent in 2019. The CDC does not mention that drop either, although it would not have been affected by the 2021 change in the settings where students completed the survey.

One reason the CDC ignores the declines in smoking, vaping, and overall "tobacco use" is apparent in today's report, which describes "the availability of flavors" as a factor that "might continue to promote tobacco product use among U.S. youths." The report and the accompanying press release recommend "restricting the sales of flavored e-cigarettes" as a strategy to "reduce tobacco product use and initiation among all youth."

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which seems bent on banning nearly all the vaping products currently available in the United States, has embraced this strategy. The FDA, like the CDC, takes a dim view of e-liquid flavors other than tobacco (and perhaps menthol) because teenagers like them. But so do adults, who overwhelmingly prefer the supposedly juvenile flavors that anti-vaping politicians consider intolerable.

If you are determined to ban those products, it is inconvenient to acknowledge that the result is likely to be more smoking-related deaths than otherwise would occur, since less flavor variety will make vaping less appealing as a harm-reducing alternative to smoking. It is likewise inconvenient to acknowledge that the "epidemic" of underage e-cigarette use is fading fast or that smoking by teenagers has fallen to record lows in recent years, a trend that is at least partly due to the fact that some of them are vaping instead.

The CDC, in short, is distorting the evidence to support its preexisting policy preferences. Sound familiar?

The post Why Can't the CDC Tell the Truth About Smoking and Vaping by Teenagers? appeared first on Reason.com.