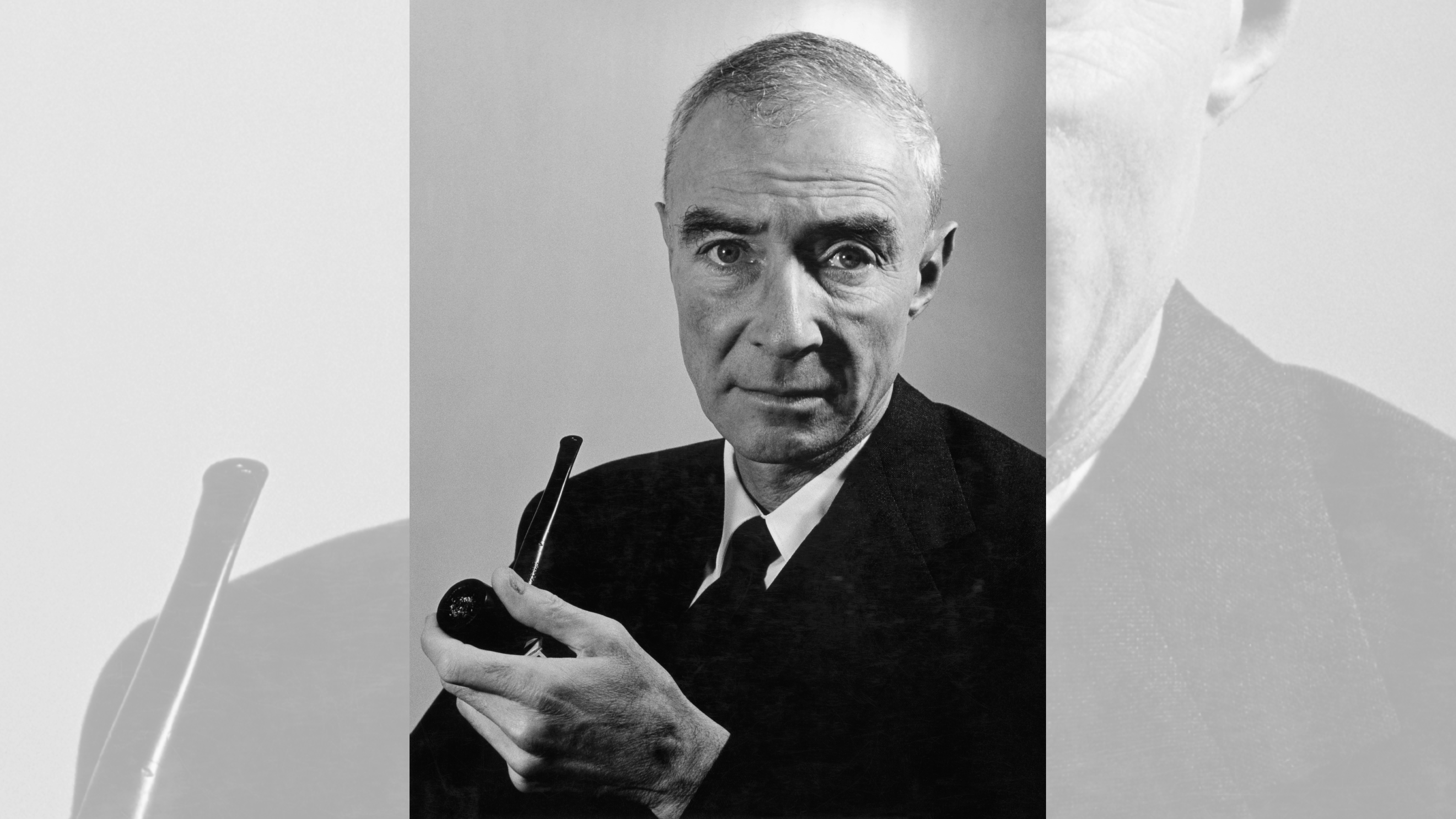

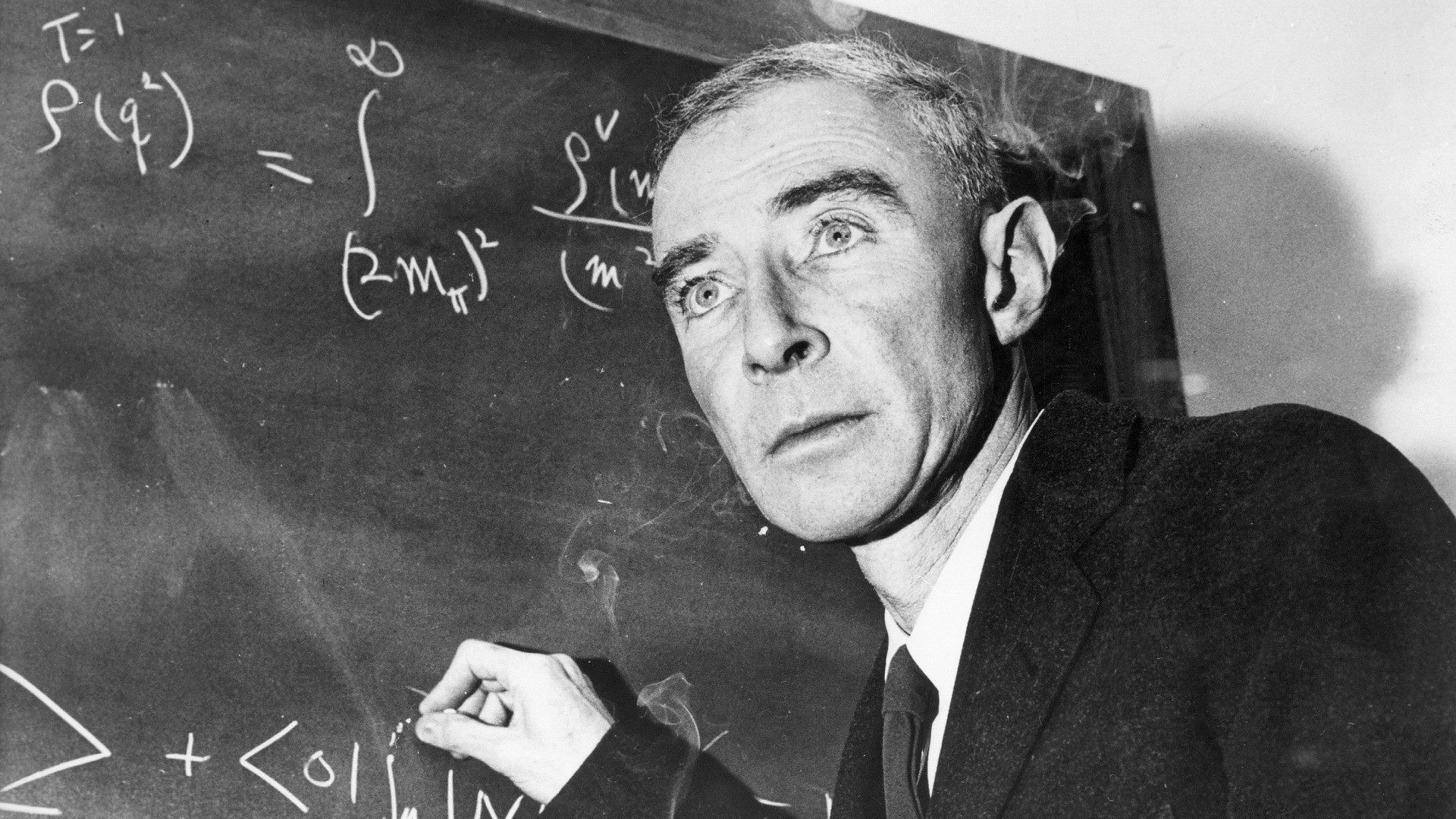

With a single tremendous flash across the New Mexico desert, J. Robert Oppenheimer — director of the Manhattan Project to develop the world's first atomic bomb — became the most famous scientist of his generation.

The piercing light, dimming to reveal a terrible fireball growing in the sky above the July 1945 Los Alamos test site, heralded the dawn of the atomic age. A physicist, polymath and mystic, Oppenheimer recalled greeting the mushroom cloud with a line from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita that he had taught himself Sanskrit to read: "Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds."

The creation of the atomic bombs and their subsequent devastation of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought an end to World War II, beginning a new era that would transform Oppenheimer into a historical icon. Yet his remorse for what he built and his opposition to its further development drove him into conflict with the U.S. military, and the government revoked his security clearance due to his communist sympathies. Oppenheimer ultimately died a broken man.

Ahead of the July 21 release of Christopher Nolan's biopic "Oppenheimer," Live Science sat down with historian Kai Bird, Oppenheimer's biographer and co-author of "American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer" (Knopf, 2005), the Pulitzer Prize-winning book that inspired the film.

We discussed Oppenheimer's rise and fall, his development of the bomb, and the way he altered human history forever.

Live Science: The Manhattan Project was an immense effort. It took thousands of scientists working tirelessly throughout the war — spending the modern-day equivalent of $24 billion — before it was completed. How instrumental was Oppenheimer in the construction of the bomb? What was his motivation for building it?

Bird: Well, he became the director of the scientific lab for the Manhattan Project, and it was his notion to have the main lab and build the bomb in Los Alamos. He built the gadget in two and a half years, and everyone who worked on it that we interviewed all said that it would never have happened if Oppenheimer had not been the director. He inspired people to work hard and to figure out, in a timely fashion, all the various engineering problems associated with building the bomb.

As for his motivation, it was quite clear. As a young man, he studied quantum physics in Germany under Max Born. While there, he'd attended lectures by [Werner] Heisenberg — the famous German theorist of quantum mechanics' uncertainty principle — and he knew that Heisenberg and other German scientists were just as capable as he was of understanding the physics of the atomic bomb and the potential for a weapon of mass destruction, and he feared that by 1942, the Germans were probably 18 months ahead in the race to build this weapon.

Politically, he was a man of the left. He feared fascism and feared that the German scientists were going to hand this weapon of mass destruction to Hitler, who would use it to win the war. That was his worst nightmare.

Live Science: Yet by the time they had built and successfully tested the bomb, his motives had become muddied. You write that he was anxiously puffing his pipe, repeatedly referring to Hiroshima's citizens as "those poor little people." Yet that same week, he was giving the military precise instructions on how to make the bomb explode over them with maximum efficiency.

Bird: I'm glad you picked up on that. It's a really incisive anecdote that gives you a sense of the man, his complexity and his ambivalence about what he was doing.

By the spring of 1945, all the Los Alamos scientists working so hard to build this gadget knew that the war in Europe was over. So why were they doing it? They actually had a meeting to discuss this difficult political issue. Oppenheimer attended — he stood at the back of the room, listened to the arguments and then stepped forward to quote Niels Bohr.

Bohr had arrived in Los Alamos on the last day of 1943. He greeted Oppenheimer with, "Robert, is it really big enough?" He wanted to know if the gadget was going to be big enough to end all war.

Oppenheimer made this argument to his ambivalent scientists in Los Alamos. He told them that this weapon is known now, there are no secrets behind the physics, and the power and awfulness of this weapon needs to be demonstrated in this war. Otherwise, the next war is going to be fought by nuclear-armed adversaries, and it will end in Armageddon. That was the argument. It was an interesting argument. It was also a rationalization.

Live Science: After the war, Oppenheimer became nuclear weapons' most vocal critic — resisting efforts to make a more powerful hydrogen bomb and referring to the Air Force's plans for massive strategic bombing with nuclear weapons as genocidal. What caused this reversal, and how did the military and intelligence establishments react?

Bird: This is what leads to his downfall. Because very soon after Hiroshima, we know from the letters that Kitty, his wife, wrote to friends that Oppenheimer had plunged into a deep period of depression; he became extremely morose.

Then he went back to Washington, and he learned more about how close the Japanese were to surrendering in September 1945. And he also learned more about the attitude of those in Washington and of the Truman administration to this new weapon — i.e., they want to build more of them and make U.S. national security entirely dependent on a huge arsenal of these weapons.

Oppenheimer thinks this is a mistake. As early as October 1945, he gave a public speech in Philadelphia in which he said that these weapons were weapons for aggressors. They are weapons of terror, they are not weapons for defense and the U.S. needs to find a way to construct an international control mechanism to prevent their proliferation.

He was coming out against the notion that we should rely on these weapons for our defense. And that was a direct threat to the War Department, the Army, the Navy and the Air Force, who all wanted bigger budgets to acquire more of these weapons.

So Oppenheimer became a threat. And this was precisely what led, in late 1953, to the first steps to strip him of his security clearance, put him on trial in a kangaroo court setting and publicly humiliate him.

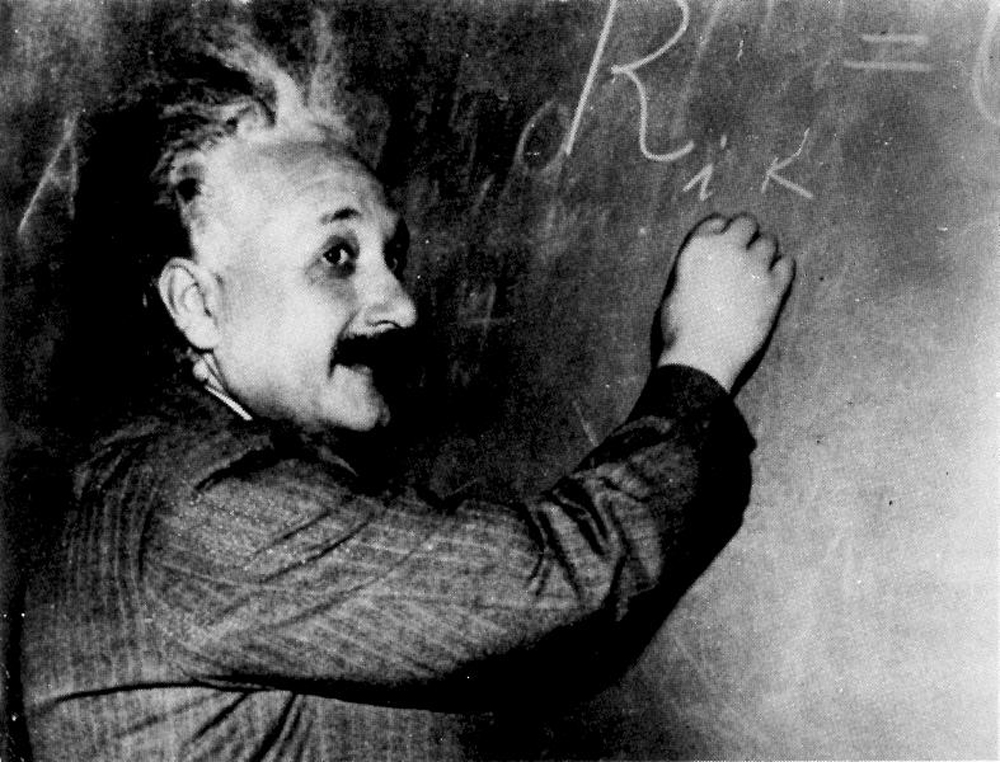

Live Science: Some of the people who knew Oppenheimer felt he was — in the words of his fellow physicist and friend Isidor Rabi — someone who "never got to be an integrated personality." And Einstein referred to him using the Yiddish word "narr": fool. What were they getting at with these remarks?

Bird: Oppenheimer was a polymath and somewhat of a mystic, and he was attracted to Hindu mysticism, which Rabi thought was a sign of a less-than-integrated personality. But I do think Rabi was onto something. And Einstein too.

Before his trial in 1954, Oppenheimer visits Einstein to explain that he's about to go down to Washington. He tells him he'll be absent from the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton [where Oppenheimer served as director from 1947 to 1966] for some weeks because he's going to be put on trial in this security hearing.

And Einstein turns to him and says something along the lines of, "But, Robert, why are you bothering if they don't want you and your advice anymore? You're Mr. Atomic; just walk away." Oppenheimer replies with, "Oh, you don't understand, Albert. I need to use my status and my platform to influence Washington policymakers and give them my advice. They don't understand this technology, and I need to use my celebrity for a good purpose."

Related: 8 wild stories about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the 'father of the atomic bomb'

In fact, Oppenheimer was fighting the security hearing precisely because he wanted to be a player. He wanted to be inside the establishment. He wanted to walk the halls of power in Washington and to have meetings with the president in the Oval Office. He was attracted to all of that, and he found it difficult to walk away from. So after Oppenheimer leaves the room, Einstein turns to his secretary and says, "There goes a nar."

And yes, he was being foolish and naive, politically. He had no idea what he was about to walk into. The security hearing in Washington was all rigged against him. He'd made really powerful political enemies in Washington, and he was going to be destroyed. Einstein was right to call him a narr.

Live Science: Oppenheimer's legacy is tied to a terrifying weapon that we have avoided using in war again. Let's say we skip 100 years or so into the future. How do you think people will remember him?

Bird: That depends on what happens and how well we live with the bomb. Say that in the next few years or decades there's another nuclear war. Oppenheimer is going to be seen as the scientist who is responsible for that, too.

The incredible thing is, we will still be talking about him in 100 years. Human beings are increasingly drenched in science and technology. We're now going to be grappling with artificial intelligence. You would think that we would be turning to scientists and technology experts to ask the right questions about how to integrate all the science into our daily lives without destroying our humanity.

And yet, many people seem to have an innate distrust of scientists and expertise. I trace some of that back to the roots of Oppenheimer's public humiliation in 1954. It sent a message to scientists everywhere: Do not get out of your narrow lane, do not become a public intellectual and do not speak out about politics or policy.

But, unfortunately, that's precisely what we need. We need more Oppenheimers who are willing to speak the hard truths about how to integrate science and make it so that it's not destructive but an empathetic part of our human existence.

Editor's note: This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.