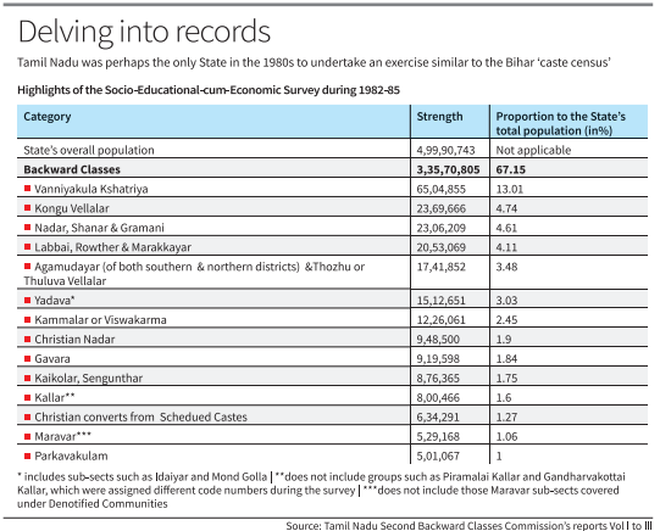

The recent release of the findings of the Bihar Caste-based Survey-2022 has led to clamour among several political parties in Tamil Nadu for a similar exercise. However, it is interesting to note that the southern State was perhaps the only one in the 1980s to undertake such an exercise, through what was then called the Tamil Nadu Second Backward Classes Commission, also known by the name of the commission’s chairman, J.A. Ambasankar, a former civil servant. Just as the circumstances in which the commission was constituted, its findings were also controversial, if not more. In fact, despite receiving the panel’s report in February 1985, the government did not make it public immediately. Also, at the end of the commission’s tenure, the chairman found himself in minority, as 14 of the 21 members differed from him and presented what was titled a “majority members’ recommendation”.

Income limit made mandatory

It all began in July 1979, with the AIADMK government, headed by M.G. Ramachandran, making the income limit of ₹9,000 a year mandatory for the Backward Classes to avail themselves of concessions, including reservation. The MGR government had only acted on a suggestion of the First Backward Classes Commission (1969-70), headed by A.N. Sattanathan, another former civil servant. But the action backfired, with the AIADMK-led coalition suffering a huge setback in the 1980 Lok Sabha election, though a Full Bench of the Madras High Court had upheld the constitutional validity of the order fixing an income limit for eligibility. On January 24, 1980, the Chief Minister announced not only the withdrawal of the eligibility criterion but also an increase in the quantum of reservation for the Backward Classes from 31% to 50%. When this was challenged in the Supreme Court, the government gave an undertaking before a Constitution Bench in October 1982 that it would establish a commission to review the existing enumeration and classification of the Backward Classes. This was how the Ambasankar Commission came into being in December 1982. At least a dozen members were all political leaders or members of the legislature. They included Pazha Nedumaran, Anbil Dharmalingam, Kumari Anandan, G. Viswanathan, S.R. Radha and K.S.G. Haja Shareeff.

The manner in which the commission conducted its work was quite impressive. It first issued a questionnaire to members of the public, covering a wide range of subjects touching the population of each community. During June-November 1983, it held sittings in the headquarters of all 17 districts, and collected over 1,600 representations, apart from oral submissions. Besides organising two seminars on the theme of backwardness, the commission deployed the government machinery to collect details of each community, reserved or not. It covered one crore households. (However, its report did not throw light on the break-down of communities in the categories of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and unreserved). As Census was a Central government subject, the commission called its exercise a survey, points out P. Radhakrishnan, former professor of sociology at the Madras Institute of Development Studies. Random sample surveys were also done to ascertain the social and educational backwardness.

Influenced by two factors

A perusal of the commission’s report would reveal that Ambasankar was, among others, influenced by two important factors — limits to reservation and the need for skimming off the creamy layer in each backward class. As for the first aspect, the report had, while retaining the 18% quota for the Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, recommended that the quantum be scaled back from 50% to 32% for the Backward Classes (there was no specific category called Most Backward Classes for the purpose of reservation in the early 1980s).

Citing the decisions of the Supreme Court, the commission said there should be no “unreasonable and excessive reservation, i.e. more than 50 per cent.” As for the second, Ambasankar’s foreword captured what he had in mind: “The labour of the Commission would be more than amply rewarded if this report helps in any small measure in the uplift and advancement of the really backward classes which have been for a long time undergoing untold sufferings.” Also, he was categorical in saying that only those communities, which passed the test of adequacy in representation in government services, would be eligible for quota in appointments, though they might have been covered under the category of ‘socially and educationally backward classes’. In fact, he had prescribed compartmental reservation which, he justified on the grounds of justice and equity.

Exclusion and inclusion opposed

However, the report came in for condemnation. Critics, many of whom were members of the commission themselves, were opposed to the proposals for exclusion of 34 communities and inclusion of 17. They were all against any reduction in the quantum. A news report published by The Hindu on April 5, 1985, mentioned that the dissenters (those commission members who did not agree with the chairman) “are pushing for 67 per cent”.

On the issues of reviewing the existing enumeration and classification of Backward Classes and the 50% limit, “it is clear that the Chairman has found himself virtually isolated”, the news report said. Eventually, the government, according to another news report on August 1, 1985, decided to include 29 more communities, taking the total to 201.

After 35 years, the report was resurrected by the AIADMK government in February 2021 at the time of getting a Bill through the Assembly to provide Vanniyars or Vanniyakula Kshatriyas with 10.5% reservation in education and employment within the overall quantum of 20% for the Most Backward Classes. During the hearing before the Supreme Court, the manner in which the Ambasankar Commission carried out its work to identify the Backward Classes was highlighted. The Supreme Court, while reiterating the decision of the Madras High Court in quashing the Bill, had pointed out that the data of the Ambasankar Commission were not contemporaneous. Yet, its work continues to ignite intense debates in political and academic circles on the subject of reservation.