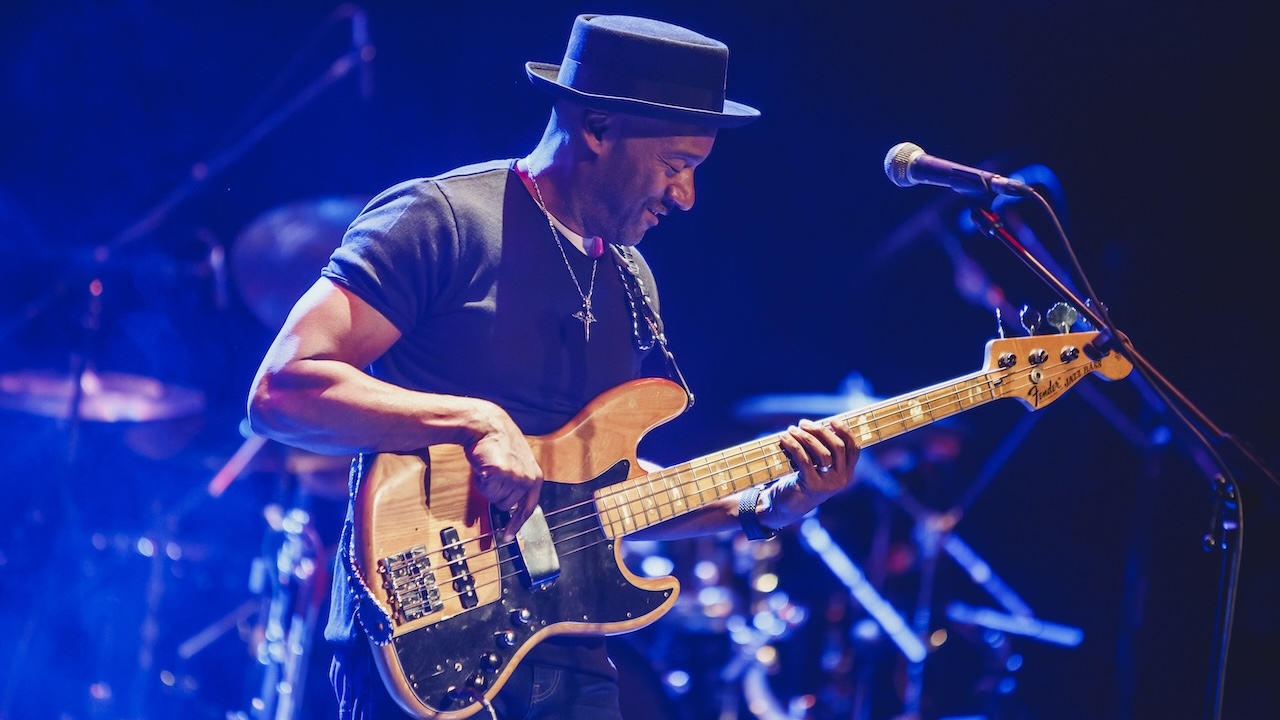

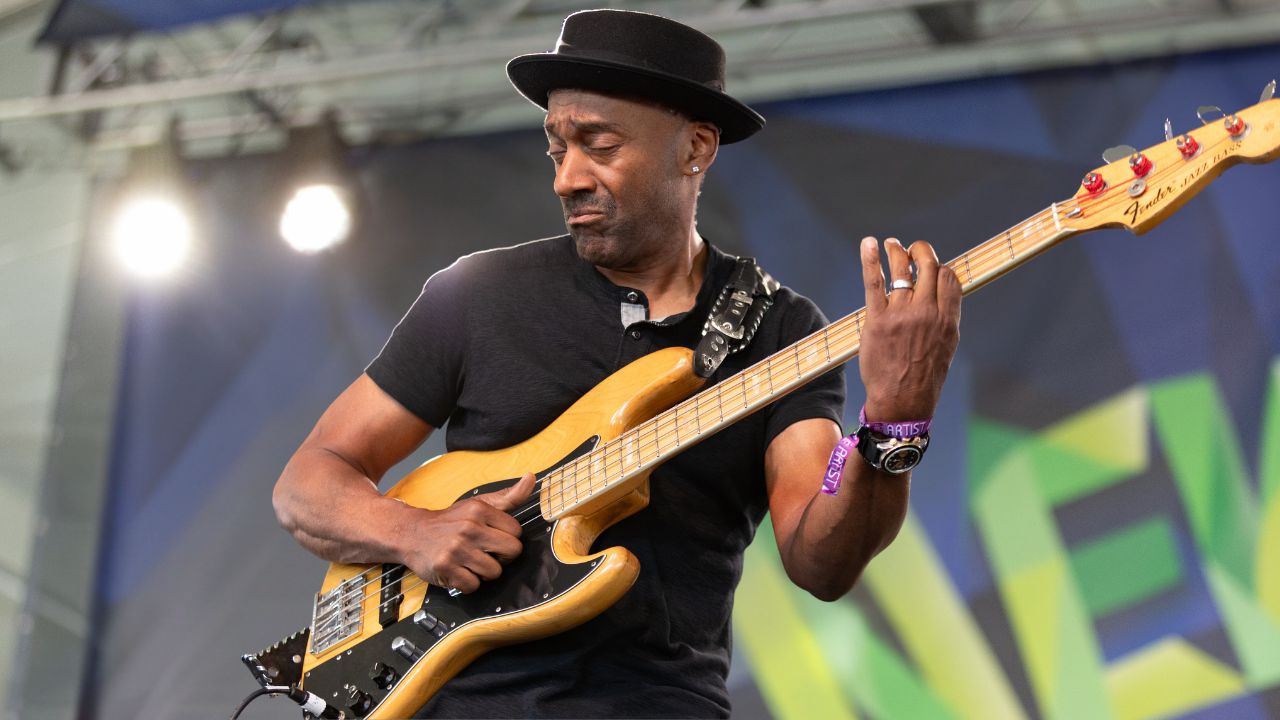

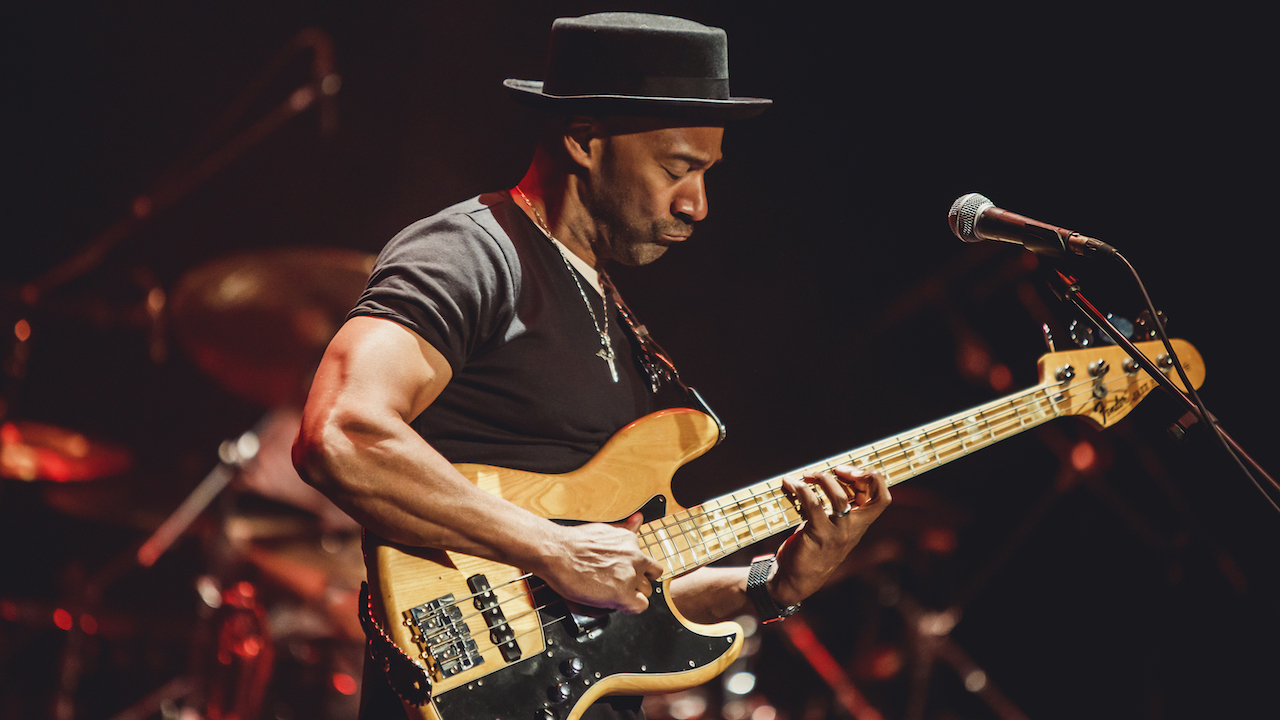

Marcus Miller personifies the cool bassist. He rubbed elbows with Miles Davis, and even his speaking voice is rife with the trumpeter's jazz slang. But Miller is far from arrogant. Instead, he communicates in thoughtful, casual tones, often delivered at a pace that evokes his back-of-the-pocket basslines.

Of course, his musical voice is much louder. There are his unmistakable compositions, with their textured jazz-hop grooves and moody, open harmonies stalking sing-song melodies. And then there's his slapped and plucked '77 Jazz Bass, which fast became a sonic presence to rival Jaco's fretless.

In addition to his work as a sideman, Miller’s solo career has yielded several esteemed recordings, including the 15-track Silver Rain, which features thunderous bass anthems, ballads, and a title track co-written with Eric Clapton (who also provided the lead vocal and a solo).

Miller's usual run for covers was also in place, with the works of no less than Duke Ellington, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Wonder, Prince, Edgar Winter, and even Beethoven reshaped to flow from his fertile mind to his funky fingerboard.

“I've settled into the concept that covers are a key part of jazz history,” Miller told Bass Player. “It raised some eyebrows when people first heard Coltrane's version of My Favorite Things or Miles covering show tunes, but now they're among our most treasured jazz performances.

“Doing a song people already know tells them so much about you and how you see the world, because they have a reference. I think it's important to have a balance, but I like what covers reveal about an artist.”

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in April 2005. We spoke with Marcus before a Japanese tour to discuss his playing style (including the profusion of Marcus clones), and the cool effect on Silver Rain.

What led you to cover Prince's Girls and Boys?

“I'm a big fan; he's an incredible artist, and his bass playing is just crazy. I learned so much about phrasing and attitude on the bass from his 1980 album Dirty Mind. But Ive always liked Girls and Boys because of the baritone sax line; I thought I could do it on bass clarinet to give it an off-center vibe.

“I also like to force myself into different keys; this one is in Bb, which is weird for funk bass. Anyway, I went back to the original once and then did it off the top of my head. I play the melody on my 1977 Jazz. I wanted someone with a lot of character in their voice to sing the hook, and I was fortunate to get Macy Gray.”

Form- and arrangement-wise, your covers of Frankenstein, Boogie On Reggae Woman, and Sophisticated Lady stay fairly close to the originals, in contrast to Power of Soul, which has new material.

“We generally wanted to get to the solo sections and let everyone play, because improvisation was a big part of doing these songs live. Frankenstein was one of those tunes people dug in all the different neighbourhoods back in the '70s, so it's a good piece to bring everyone together. I did it from memory, having last played it in clubs 20 years ago.

“Boogie On Reggae Woman was something we were fooling around with, and I thought, ‘I want to claim that bassline for bass guitar!’ Stevie Wonder's synth part is brilliant; he's got his whole heart and soul in it, and it was really hard to make it sound natural on the electric. I listened to the original to remember all the lines, because he never plays the same thing twice – no doubt from his Jamerson influence. The only change I made was to extend some of the harmonies.

“I had recently recorded Sophisticated Ladies as a guest of Solid Brass, a Japanese brass band, and I fell in love with it again. I thought it was a perfect melody for bass clarinet, which has a longing quality to it. I reharmonized it a bit, and I used my fretless Modulus 6 because I needed the upper range.”

“As for Power of Soul, we've been doing it for a while; it's a feature for Dean Brown. I built a new section from the opening riff, and we play the main riff, but we don't get to the chorus.”

Your most intriguing cover is Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata.

“I've been pointed in a classical direction from having worked on an opera CD with Kenn Hicks, and also because my son plays a lot of classical piano in the house. One day he was playing the Moonlight Sonata, and I found myself going, ‘Man – that Beethoven was a soulful cat!’

“As a kid, whenever I heard that kind of music I always added a beat or a bassline in my head, and it dawned on me that I should present the same concept to people, to show them how I reimagine this music when I hear it.

“So while my son was playing, I was getting on his nerves by playing a bassline on my upright, singing the beat, and telling him that if Beethoven had a drum set, this is what he would have told the drummer to play!”

Were you thinking vocally when interpreting the melody on your '77 Jazz?

“I used a vocal/blues guitar approach, because the groove is sort of gospel 6/8 with a backbeat. I also have blues guitarist Lucky Peterson playing fills throughout and soloing at the end of the track. The key to the melody, though, is that it's so simple and beautiful, and it's all connected with a single line.”

What inspires your techniques and phrasing?

“When I slide up to a note or bend to it, it's emulating a singer, because they usually don't hit notes right on. The hammer-ons and trills pertain to vocal vibrato, but I also use them because the fretted bass doesn't sustain as well, so I'll add a hammer-on to keep the note going. Plus, it gives the line attitude.

“I think playing other instruments helps me, too, as does the fact that I've worked with phrasing masters like Miles, Luther Vandross, and Roberta Flack. The bottom line is: phrasing is everything. It's what gives music its character. Once you've learned your scales and techniques, you have to come out the other side and realize it's all a tool, and now you have to find a way to reach people.”

Judging by the many solo bass CDs we receive, you're competing with Jaco and Victor Wooten as the most copied bass stylist.

“That's one step in all of our developments, like the kid in high-school who sounded just like so-and-so. It's a good thing at that point, but eventually it's best to move on. What helped me in high school were friends like Omar Hakim and Kenny Washington, who didn't want to sound like anyone but themselves.

“It was an ethic when I started playing the clubs in Jamaica, Queens: the only thing that mattered was whether people could tell who you were in the first three notes! Tom Browne was a master at that.

“I joined Lenny White's band at age 17, and I remember asking him, ‘How do you get your own sound?’ He said, ‘By playing in as many different environments as possible.’ Sure enough, when I got into Miles' band in 1981, playing like my idols – Jaco, Stanley, and Larry Graham – wasn't going to work in that musical setting, so I had to dig and find something else.”

“It was the same thing playing with Luther Vandross. Now you've got cats who are making their own environments with computers, and there's not a whole lot of other musicians involved in their development. They need to find other musicians to play with in order to find themselves, if that's what they value.”