It’s April 1999, and some of rock’s biggest and most respected names have banded together to record songs as part of a benefit album for one of American music’s more obscure figures. It’s an impressive line-up: Robert Plant, Tom Waits, Beck, Mark Lanegan and Greg Dulli. All are paying tribute to a man whose last meaningful music was made 30 years ago but whose legacy still burns bright.

But there’s another reason they are taking part in this homage. For the past three decades the man in question has been in declining physical and mental health, living on the streets or in care. Most recently he’s been holed up in a trailer in San Jose, California, surviving largely on a diet of anti-psychotic drugs.

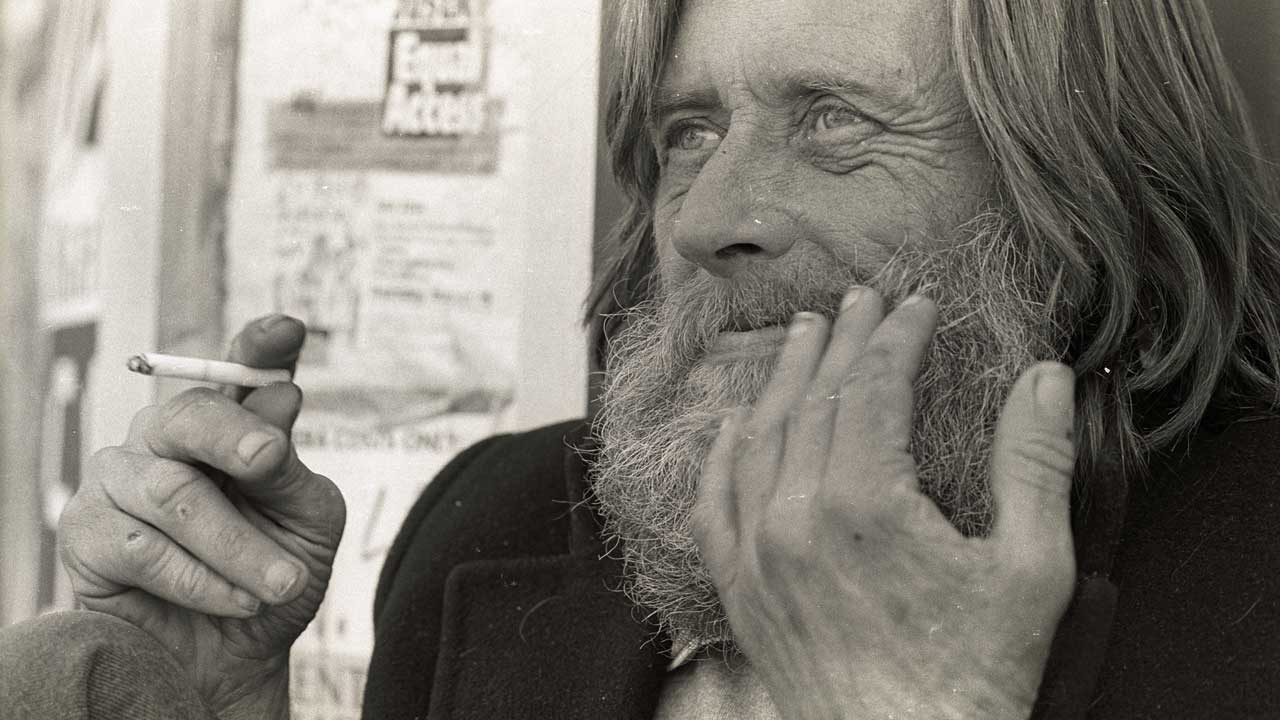

Now things have deteriorated further. Alexander Spence – ‘Skip’ to all who know him – has been admitted to the local Dominican Hospital with pneumonia. The doctors have also diagnosed lung cancer. His son Omar arrives with a promo pressing of More Oar, the aforementioned benefit album, and plays it at his bedside. Despite his condition, Skip manages a weary smile. Within the hour he’s dead, two days shy of his 53rd birthday.

Spence’s death didn’t trouble the notice pages of the dailies, but it was a heavy loss to a significant portion of the music world. His former bandmates in Moby Grape, the Bay Area group he co-founded in the 60s, felt it deeply. As did those he was an inspiration for. Robert Plant had been a Grape fan since his pre-Led Zeppelin days.

His next album, Dreamland, would feature Skip’s Song (aka Seeing), a Spence original from 1967. Bobby Gillespie cited him as a key signpost to Primal Scream’s in-progress record XTRMNTR. Julian Cope, Wilco, Chrissie Hynde and Mudhoney were also swift to acknowledge a debt.

These admirers fell into two camps. There were those who adored the buzzing psych-rock of Spence’s work with Moby Grape: Someday, Indifference and arguably the band’s greatest moment, Omaha. Then there were the disciples of Oar, the extraordinary LP that Spence made in December 1968.

Recorded after a spell in the psychiatric wing of a New York hospital, it redefined the notion of the confessional singer-songwriter. That Oar continues to resonate is a tribute to both Spence’s raw talent and his ability to map the darkest reaches of the human experience.

“I liken Oar to something by Van Gogh,” says Spence’s old producer David Rubinson. “It’s so completely accessible – emotionally, spiritually and psychologically. And I think people respond to that. They find Skip, and themselves, by accessing the music. That was the whole point.”

The tragedy is that Oar was a final outpouring of his creative self. Spence was only 22 when he made it, but his best days were already behind him.

The details of Spence’s early life are vague. Born on April 18, 1946 in Ontario, Canada, he moved to San Jose in the late 50s when his dad took a job in the aircraft industry. Spence Snr was a wartime bomber pilot, but had also been a singer-songwriter for a time, playing clubs and bars dotted along Route 66.

The free-spirited Skip didn’t seem to have inherited much from his fastidious father, except a love of music. He began playing guitar aged 10, and by his late teens was playing rhythm in an East Bay surf combo called The Topsiders.

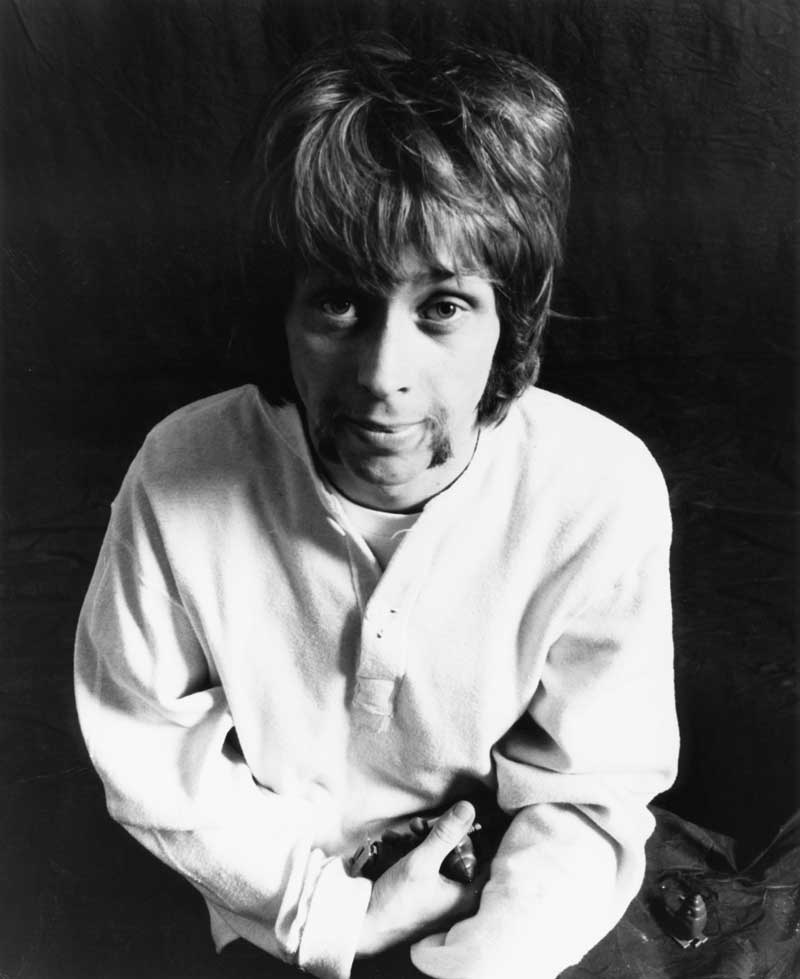

In 1965 he passed an audition for Quicksilver Messenger Service, whose rehearsal space was The Matrix, a San Francisco club owned by Marty Balin. Balin, needing a drummer for his new band, Jefferson Airplane (pictured above), caught sight of Spence at the bar.

“Skippy was this beautiful kid, all gold and shining,” Balin told biographer Jeff Tamarkin. “I just saw him and said: ‘Hey, man, you’re my drummer.’”

Despite Skip’s assertion that he was a guitarist, Balin handed him a pair of sticks and told him to practise. A week later, despite no prior experience, Spence returned as a more than capable drummer.

He was aboard for 1966’s debut, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, which included two co-writes with Balin: Blues From An Airplane and Don’t Slip Away. But by the time it was released in August ’66 Spence was more or less gone. Balin sacked him after he missed a gig, disappearing instead to Mexico with two girls. But bassist Jack Casady offers another reason: “Skip was really multi-talented, with a good energy about him,” Casady says. “He wanted to write songs and play guitar. But the Airplane had enough of those people already.”

Jefferson Airplane’s ex-manager, Matthew Katz, had also been drawn to Spence’s magnetic personality. After Spence turned down an offer to replace Dewey Martin in Buffalo Springfield, he threw in his lot with Katz, and together they hatched plans for a new band: Moby Grape.

The group were almost embarrassingly gifted. Guitarist Jerry Miller had toured with Texan rock’n’roller Bobby Fuller; drummer Don Stevenson had played with blues greats Etta James and Big Mama Thornton; bassist Bob Mosley possessed a fabulous white-soul voice; and there was rootsy guitarist Peter Lewis, whose repertoire spanned folk and country.

The five members made for an irresistible combination. All of them were singer-songwriters. Between them they could harmonise like The Byrds and tear it up like the Stones, while their three-guitar thump provided the same dizzying thrills as Buffalo Springfield. Plus Moby Grape were sensational live.

A regular slot at Sausalito club The Ark proved a huge draw for San Francisco’s in-crowd. “We made friends quickly there,” says Lewis, “partly because they wanted to find out what kind of a band Skippy was in. He was absolutely indispensable – a great arranger and songwriter, with an incredible stage presence. He was promoting the whole thing.”

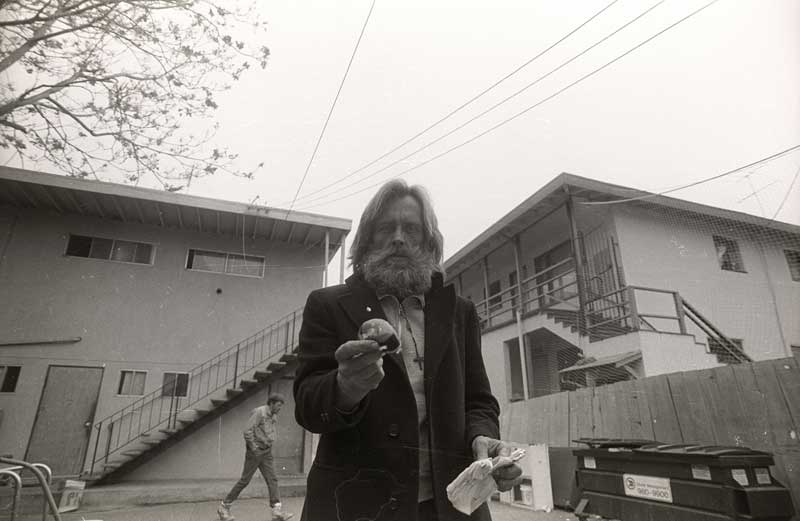

An early visitor was David Rubinson, who fetched up at the Ark to watch The Sparrows, a band he was producing for Columbia Records. The Sparrows would soon rename themselves Steppenwolf, but it was the support act that stole his attention. “Moby Grape was the best American band I’d ever seen,” he recalls. “I was completely blown away. Everybody could sing. But Mosley and Spence were the energy. They were both murderously intense. So I rented an apartment for my wife and son, and we stayed in San Francisco until I got them signed to Columbia.”

Rubinson took the band (above, with Spence on the right) into a Hollywood studio in March 1967. The resulting album, simply titled Moby Grape, was a flashing distillation of West Coast pop. Searing R&B rubbed up against pithy balladry, and huffy garage-rock jostled for space with echoey weirdness and killer harmonies. These were songs as artful as they were urgent, fizzing with a very peculiar intensity. Unlike most of their Bay Area peers, the band didn’t concern themselves with lengthy jams or improvised blues, and instead wrote concise rock songs that cut through the hippie-dippy bullshit.

Songs such as Omaha and Indifference showed that Spence was a master when it came to great chord changes and sudden hooks. “They came in to listen to the first couple of takes,” Rubinson remembers of the sessions, “and Skip was upset: ‘David, that’s not enough. When I hear it I don’t wanna hear it with my ears, I wanna hear it here!’ He was pounding on his chest.”

Moby Grape remains a landmark debut. “It’s in my top three albums of all time,” says uber-fan Chrissie Hynde. “Years later I realised that I’d lifted something for The Pretenders. I was listening back to Someday [co-written by Spence] and thought: ‘Wow! That’s where I got Talk Of The Town.’”

Moby Grape did well, reaching No.24 in the US and hanging around the Billboard chart for the best part of six months. But fate was already conspiring against the band. Columbia had poured obscene amounts of money into a disastrous press launch at San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom, carpeting the venue with orchids and handing out hundreds of bottles of Moby Grape wine.

In an act of pure hubris, the label took the decision to release five singles at the same time, convinced that each would be a massive hit. Instead the radio stations were confused as to which one to play. The upshot was that only Omaha charted – at a desultory No.88. If ever there was a band that didn’t need the hard sell, it was Moby Grape.

Intrigued by the hype, the authorities came calling. The night of the Avalon bash ended with Spence, Lewis and Miller being arrested at a party, and held (wrongly) on suspicion of dope possession and contributing to the delinquency of minors. All charges were soon dropped, but the headlines ensured Moby Grape now had a reputation.

Promoters began pulling gigs. Columbia reacted by sending the band out on a tour supporting the Mamas And The Papas. It didn’t go well. Unruly behaviour and storming stage performances only undermined the more mellow headliners. The Grape were soon kicked off the tour.

But these were mere trifles compared to the real damage. In their naïvety, the band had unwittingly signed away their publishing rights to Matthew Katz. And the rights to the band name. It was a decision that would haunt them for decades.

“We were going to sign for Elektra,” explains Lewis, “but were already signed up to Katz for the Moby Grape name. Elektra said we could change it if we wanted. But Katz went to Skippy and said: ‘We don’t want these guys to throw you out like the Airplane did, right? Well, you’re gonna have to get them to sign the name over to me because then I can protect us.’ So Skippy did that. Then Katz betrayed him. Skippy took that on himself as his failure. He believed in people with a faith beyond reason. And when they didn’t conform to his highest hopes it would destroy him.”

If Spence had yet to realise the full consequence of the Columbia deal, what happened next was far more disturbing. In an attempt to curb the band’s wild partying, the record company insisted that the Grape repair to New York for their second album, Wow. The result was a series of disjointed sessions. Lewis even quit temporarily at one point and headed home in an attempt to save his failing marriage.

Spence contributed Funky-Tunk, Motorcycle Irene and the bizarre Just Like Gene Autry: A Foxtrot. The latter featured old-time radio broadcaster Arthur Godfrey, who was recording in the studio next door, introducing what amounted to a pre-war dance orchestra parody. The song came with instructions to play it at 78rpm.

By contrast, Seeing (which failed to make the final cut) offered a window into an increasingly troubled soul. ‘Can’t beat a dream of death today,’ Spence sings, ‘Hard to get by when what greets my eye takes my breath away.’ It closes with what sounds like a desperate plea for his own sanity.

“Jesus Christ, what a great song,” Rubinson marvels. “He sings it so beautifully, then starts going: ‘Save me!’ He was talking about this horrible woman that he’d met. Joanna was a groupie who scored the drugs – blue cheer [a pill that combined LSD and Methedrine] or whatever it was. That’s who I think he was writing it to. Skip was a medium and would simply express what was coming through him.”

According to the Grape, Joanna was a self-proclaimed white witch. She and Skip had been living in Greenwich Village, ingesting all manner of hallucinogens. For a man whose temperament was already hovered at the extremities, it was all too much. “Skippy got in with a bad crowd and was doing a lot of drugs,” sighs Jerry Miller. “One day he’d be looking good. The next time I saw him, his beard looked like he’d chopped it off with an axe, he was all sweaty and not making much sense.”

Things came to a head when the delusional Spence took a fire axe from the Albert Hotel, where the band were staying, and went looking for Don Stevenson, believing him to be possessed. Having hacked down the drummer’s door, only to find the room empty, he jumped in a taxi and headed to the studio. Skip’s quarry wasn’t there either. In fact the only people around were Rubinson and engineer Roy Halee.

“Jerry and Don called me and said: ‘David, Skip’s coming up to the studio to kill you,’” says Rubinson. “So we locked the doors, then called security. Skip arrived in a taxi, with an axe, in his pyjamas. I was waiting for him in front of the studio. I had no idea what to do, but I just walked over and talked to him: ‘C’mon, man. You’ll be okay, it’ll be okay.’ He was scared, wild-eyed. Somehow he let go of the axe, and the only thing I could think to do was call the police and have him taken to Bellevue.”

Spence was admitted into the psychiatric ward of Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital in June 1968. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, he remained there for six months. His bandmates tried to pick up the pieces back in San Francisco.

Upon his release, Skip’s only possessions were the blue hospital-issue clothes he was wearing. Rubinson met him at the gate, took him uptown, bought food and fresh threads, then booked him into a hotel. It transpired that Spence hadn’t been idle in Bellevue. He told the producer that he wanted to record some new songs he’d written. Having been deprived access to a guitar during his incarceration, he explained that he needed to get them down while they still burned in his head.

Rubinson went to the record company the next day and secured a modest advance. Spence promptly bought a Harley-Davidson and set off for Nashville, nearly 900 miles away. He entered Columbia Studios on December 3. Within six days he’d cut nearly 30 songs. That feat was made all the more impressive by the fact that he did everything himself: vocals, guitars, bass, drums, arrangements, production. His only companion was Rubinson’s trusted engineer, Mike Figlio. The instructions to Figlio had been simple: just keep the tape rolling.

The common myth is that the resulting album, Oar, represents the scattered mutterings of a man for whom reality was already a tenuous concept. In truth, it’s a record of often startling clarity. And even when Spence appears to be drifting in and out of conscious thought – as on Grey/Afro – there’s a surety of touch that suggests a very deliberate narrative.

The songs themselves are lo-fi, delivered with the kind of lugubrious wisdom that make a nonsense of Skip’s young age, 23. The overall mood is claustrophobic, even slightly oppressive. Yet Oar has some beautiful melodies. Little Hands, later covered by Robert Plant, could easily have been a hit. Cripple Creek and Weighted Down (The Prison Song) sound like the work of a Delta bluesman.

There’s also a good deal of humour. Lawrence Of Euphoria is a lusty novelty song, Spence introducing ‘Vivian from Oblivion’ and ‘Ellie Mae from Californ-i-a/She does it all right but her lips are tight/She tucks me into bed at night’. Oar is laced with puns, wordplay and alliterative tics. The subject of Margaret/Tiger Rug is an ice skater: ‘If she wasn’t so daring and dashing/Her lips would be chapped at half the price.’ That line that tickles Rubinson to this day.

“That’s really the essence of him,” he says. “Oar is really dark, but before that Skip was a very light, humorous person. He was a happy guy, but also extremely fiery. He could get insanely angry. Skip had demons, like we all do, but he was really more at the mercy of them than most people.”

The darkness and demons that Rubinson refers to form the central pillars of Oar. Skip’s anguish is apparent, for example, in the simple lines of Diana: ‘Tears fall like rain/Oh oh Diana, I am in pain.’ Cripple Creek’s protagonist imagines himself free of the mortal realm, angels flying to greet him and whispering in his ear. Mirroring Skip’s own actions in Bellevue, the man in Weighted Down (The Prison Song) dispenses with material possessions, preferring instead to pine for the woman he’s lost.

There are odd religious references, too. Books Of Moses, with its sinewy acoustic guitar and sandy baritone, is soundtracked by a rainstorm and someone chipping away at a stone tablet. But it’s Broken Heart that appears to embody the prevailing mood of Oar: ‘I’d rather have no eyes at all, be blind upon the floor/Then to stand upon the receiving end of the right hand of the Lord.’ It’s an act of defiance that suggests Skip’s most cherished asset is his own individuality, his own spirit.

Oar isn’t the sound of a man falling to pieces, it’s the sound of a man trying to make sense of what’s happened to him. When he was done making the record, Spence simply sent the tapes to Rubinson in New York, got on his bike and headed back to his wife and family in San Jose.

When Oar was released, in May 1969, there was no promotion whatsoever. “When the people at Columbia heard it, Oar made no sense to them at all,” remembers Rubinson, who had sifted through the reels of tape, mixed the album and sequenced its dozen tracks. “It was so honest and real that the record company couldn’t relate to it. Neither could radio or critics. So they put it out, barely, and it sank without a trace.”

One critic who did champion the album was Rolling Stone’s Greil Marcus. His review, drawing parallels to both Frank Zappa and the campfire folk of the Californian gold rush, urged people to buy the album before it disappeared. Alas they didn’t.

Oar was rumoured to be the lowest-selling album in Columbia’s history at the time – some estimates suggest it shifted less than 1,000 copies. Within a year it had been deleted from the label’s catalogue.

“I took Skippy down to LA on the day Oar was released – the same day Neil Young’s first record came out,” says Peter Lewis. “I remember buying them both in a record store and going into a listening booth with Skip. I realised that he’d made a masterpiece and Neil’s was totally jive. But Neil got famous and Skippy went to the streets. And that’s something I live with every day.”

Spence never attempted to make another solo album. And when he hooked up with his old bandmates again he was in poor shape. Moby Grape ’69 features him more or less in name only, with the band reaching back into the Wow sessions and finalising a version of Seeing.

The Grape’s troubles – namely Bob Mosley’s own schizophrenia and the ongoing legal battle with Matthew Katz – meant that the band was now an on-off concern. Spence was still able to exert some influence, though. Rubinson credits him with bringing them back together to record 1971’s 20 Granite Creek, although Spence’s contribution amounted to a single song, Chinese Song.

“By this time Skip was really far gone,” Rubinson says. “He was a heroin addict. But he found this house in San Jose and we all moved in. We set up the recording equipment in a truck outside and put the instruments in the living room. He was the energy that drove it, but he was so junked-out that he couldn’t really participate.”

Spence’s growing addiction to drugs and alcohol meant that he was unable to sustain much of a career at all. In 1970 he’d had a regular gig with a band called Pachuko at a biker joint in the Santa Cruz mountains. By ’73 he was with another band, The Yankees. The story goes that, in October that year, Skip OD’d and was shuttled off to a San Jose hospital, where he was pronounced dead. Lying in the morgue, with his toe already tagged, he suddenly sat upright and asked for a glass of water.

Whatever the truth, when Moby Grape attempted to reunite five years later, Spence had deteriorated badly. “Skippy was something else at that point,” remembers Peter Lewis. “There was a demonic residue from what had gone on in New York during Wow. It was similar to what the Catholics used to tell me about possession. That’s what the acid does to you. He was having visions of axe murderers.

"We realised we had to find him someplace else to live, because he was bad for business. So we got him a house. He’d be out there, with no teeth and his hair down to his ass. He never washed. He had this rat called Oswald and they’d both get in there and snort cocaine. It was way beyond the guy that I’d met when I first went to San Francisco. He was very energetic and positive back then – Mr Love – but he just turned into this dark character. I guess there was a line that he crossed and he could never get back.”

Lewis also relates a scary story about taking him to a monastery in Big Sur, where, after a night in which he heard Spence being violently thrown against his cell wall by forces unknown (“there were voices that sounded animal-like”), he asked the resident priest to perform an exorcism. Instead they were told to leave.

In 1981, living either as a hobo or in temporary accommodation, Spence became a ward of the state of California. One of his old songs, All My Life I Love You, fetched up on 1989’s Legendary Grape album, recorded by his old cohorts as The Melvilles. Skip continued to write, and even sat in on a number of reconstituted Moby Grape gigs in the early 90s. His last live appearance with them was in 1996. The same year, he was commissioned to write a song for The X-Files soundtrack. The result, a strange spoken-word piece called Land Of The Sun, was deemed too weird for inclusion.

Decades of mental illness and substance abuse had exacted a heavy toll on Spence, but his ex-bandmates often dropped by his San Jose trailer in those final years. Lewis would take along his guitar and they’d just jam. Skip also became a Christian in his later life, which, says Lewis, brought him a degree of peace. When he died, in April 1999, the remnants of Moby Grape gathered together in Santa Cruz for an informal night of music-making that served as a wake. Jerry Miller later recounted that Robert Plant picked up the bar tab. He’d also helped with Spence’s medical bills.

By then, Oar had been rediscovered by new generations of artists. First reissued by Sony in 1991, it was followed eight years later by an expanded version on Sundazed. Mark Lanegan was just one of those who fell under its spell. “I discovered Skip when he was mentioned in a review I read of my first solo record,” he explains. “He’s one of the great lost songwriters, and Oar is total brilliance. It’s all over the map, but it’s completely cohesive.”

For Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, Oar was an epiphany. “It was a revelation to hear a record that disjointed and free, to hear something that liberated,” he says. “It made me understand that a record can be anything it wants to be. That it can have traditional elements yet at the same time destroy any concept of it being nostalgia. It’s a miracle that he was able to stay together enough to even make it.”

Oar has now reached the kind of sizeable audience it merited first time around. On one hand it can be seen as a parable of the counterculture itself, with all its possibilities, freedoms and hidden dangers. On the other it’s the diary of a man who threw himself into the 60s with a rare abandon. And survived, just about, to roll out his tale.

History has tended to reduce Skip Spence to a caricature, an acid casualty to file alongside the similarly labelled Syd Barrett or Roky Erickson. David Rubinson bridles at such a view. “Skip had these demons, these incredible contradictions in his life and personality,” he says. “Whatever drug he took, the walls came down and he had unlimited access to what was raging within him.

"So I don’t blame the drugs, but that was the key that unlocked the door. I read a lot of stuff in the press about him being crazy, but he was not. He was desperately in touch with the biggest realities in the universe. Somehow he could see and feel things that were enormous, meaningful, global. And he suffered from that because it was so painful.”

Oar, Rubinson says, was his way of sharing it. “He was saying: ‘I am showing you everything, every ounce of my vulnerability.’ And that’s a fantastic legacy to leave, because it should inspire us all.”