I listen to people on the news discussing what we’ve learnt from the pandemic. It’s all about PPE, the Government and vaccines and the crisis we have endured is presented in stats, graphs and sound bites.

I look back with a different perspective. I am a senior sister in critical care at St George’s Hospital, Tooting, southwest London. Throughout the crisis I worked in the Covid intensive care units, and saw life – and death, sadly – on the NHS frontline. The stats, graphs, soundbites, politics and economics – for me, it’s not about any of that.

Instead, I experienced love, resilience, compassion, and hope. I remember the human stories. And most of all, I think about people and how this pandemic showed just how big the human capacity for love is, even in the most unforeseen and dire situations.

I wrote about my experiences in weekly emails sent, at first, to friends and neighbours. Soon, they were circulated and forwarded and the readership grew (and included people like Sir Richard Branson and Susanna Reid).

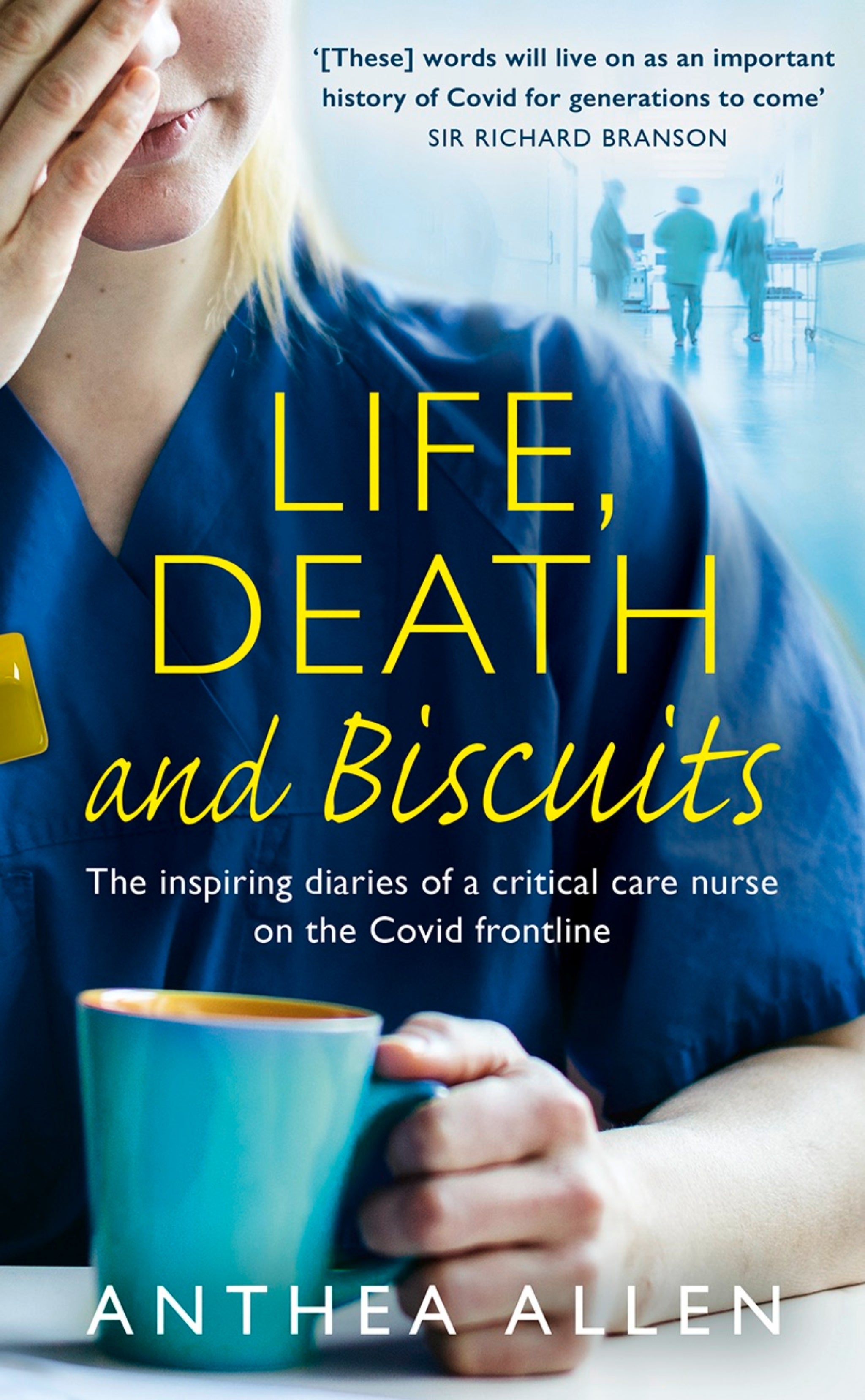

That first email, back in March 2020, was a plea for donations of cake and biscuits for the nurses and staff on Critical Care at George’s. A small but significant act of kindness for the nurses who were catapulted into a brand-new frenzy of Covid. which would later be complied into my first book, Life, Death and Biscuits.

We were now at war with an invisible enemy and our usual protocols had been thrown out the window

We were now at war with an invisible enemy and our usual protocols had been thrown out the window. Those cakes and biscuits were a much-needed ray of human kindness in the unknown darkness. The family and friends of patients we used to be able to offer a needed hug or squeeze to were now separated from us, and their loves ones, by screens and technology. The reassuring smiles and eye contact they needed from us, hidden behind masks and visors.

In response to the kind donations of food and sweet treats, I provided an account of our day-to-day life as nurses working to care for those struck down with this deadly virus. Through the worst times medical staff have ever worked through, an incredible group of warriors rose up and fought back. We offered each other hugs in PPE, a shoulder to cry on when many were separated from their families by travel restrictions and yes, the occasion flash of glorious, human humour that briefly made us forget what was going on around us. Like the man who, having only just recovered his ability to keep down fluids, grimaced after sipping his first cup of tea in weeks and said whilst shuddering “not Earl Grey”.

I have enormous respect for Critical Care nurses and this experience only confirmed what I already knew. Nurses are amazing and Critical Care nurses are trained and competent in using the equipment, monitors and medication required to nurse any critically ill person. I have eternal admiration for the nurses who united as a powerhouse of endurance, resilience, and strength to fight back and care for those affected by Covid-19.

These are two of my earliest emails, written at the beginning of the pandemic in April 2020.

12 April 2020

I have always been a chatty person. It takes a lot to take my breath away. There are no words to describe the scenes and way of working within our forever- expanding Critical Care.

ICU nurses are meticulous. Attention to detail is high on our list. I have many friends who carefully label the jars in their larders, as we are so conditioned to labelling drugs and equipment to ensure that we are alert to expiry dates or what a specific drug is and its dose. ICU nurses love to label.

We keep a diary for patients. This is so that when they recover, they can know their journey. If they don’t survive, feedback tells us that these diaries are a comfort to the families. We brush patients’ teeth; we change their position, the way they are lying in bed. We talk to patients who are unconscious. We explain to family. We wash hair. We smuggle in a dog to visit; we put a favourite teddy in the bed. We respect religion, race, sexuality. I have repositioned a bed to face Mecca and dropped off a Valentine card for an elderly patient’s wife.

We give the same high standard of skilled care to every person. We deal with all intimate procedures for our patients, as well as operating ventilators and supporting organ failure with specialised drugs and machinery. We are a competent, skilled, highly knowledgeable, kind, caring group of individuals who are proud to be Critical Care nurses.

It’s different now. We are in a growing storm. We fight to do whatever we can to keep someone alive, try our best to help them beat this unrelenting deadly virus.

We have nurses to help who are unfamiliar with the ICU environment. The personal care is impossible. One nurse said to me, “I don’t even know my patients’ names.”

This is not our usual place of work. There is a backdrop. It’s like being in a weird dream. We all have trouble sleeping and so many of our permanent nurses – they come from all over the world – want to go home. They probably will after this is done. We are broken.

We feel wretched and exhausted and tired while at work. We feel guilty when not at work

True to form, there is hilarity amid the madness. Nurses have a sick sense of humour. We are laughing and crying and supporting each other. We have offers of counselling, but the nurses are too busy and their priority outside the environment is to eat, sleep and have a very long shower. One day some of the nurses had the names of pop stars written on their gowns, rather than their own names. I didn’t recognise Beyoncé at all – a large male cardiac ICU nurse, I think. We feel wretched and exhausted and tired while at work. We feel guilty when not at work, as we know there are not enough staff with the patients. Nurses work extra days. If I am not at work, I am coordinating staffing, rushing through temporary staff, arranging ID cards and PC access, ordering supplies, planning the opening of new makeshift areas, and procuring new equipment, as well as talking to overwhelmed nurses.

I walked through one of the ICUs a few days ago and blew kisses at the nurses I know beneath swathes of fabric, plastic, and paper. Possibly I didn’t know them, but they got a kiss anyway. Today I received a text message from one of the Italian nurses: ‘Please come by and send me flying kisses again.’ I once asked this Italian nurse what had inspired her to become a nurse. “In a way, my father,” she replied. “He passed away when I was quite young. Eleven. And I think in my mind, I wanted to be a nurse. Then I could look after people because I had not been able to look after him.” She graduated as a nurse in 2014, came to England a few years ago and, after 18 months, she came to St George’s ICU. “I’d heard that St George’s was really good, and I wanted to work in a trauma centre and do a little bit of intensive care,” she said. Three years later, she is still here, in the midst of this pandemic and probably feeling a million miles from Milan.

The level of anxiety increases immeasurably each day. It’s often too traumatic and surreal to talk about what we see and do. It’s particularly tough for the junior staff who workday after day and are expected to suddenly lead and guide staff from other areas.

We live a parallel life while others take the quarantine art challenge, plan Easter egg hunts and are bored at home. We continue on and on and on, and still more patients arrive. They feel ill and scared. One man said, “Please don’t let me die.”

Thank you for your support. Keep it going. I think nurses will need support way beyond this time. Every card, email, text, WhatsApp makes a difference. The support I receive powers me on to support my incredible team of Critical Care nurses. If you know a nurse, send them a message or drop something on their doorstep.

The mortuary staff have an endless stream of dead bodies to store

This is a different way of nursing. Unchartered, with no end in sight. There are many NHS workers, some unseen, who are struggling. The mortuary staff have an endless stream of dead bodies to store.

Our mortuary is full. The lab technicians have to process the stream of swabs, as well as their daily testing of blood and specimens. Our technicians service, clean and calibrate the ventilators. At the beginning of the pandemic some of the machines we need to use are over 50 years old and repurposed. We use anaesthetic machines, designed for ventilating a patient during surgery. The pharmacy keeps up with the supply of drugs required. Recruitment are processing new, redeployed and temporary staff. Many NHS workers, the nurses and doctors on the front line and our entire team – I share your donations and messages with them too.

A junior doctor told me, “When this is done – so am I. No amount of money could make me stay.” Then she asked, “Who sent in the delicious figs?” I appreciate all the messages. I can’t always reply, as I am working or don’t know what to say.

Or it is just that I am totally exhausted. Keep safe, keep smiling and never underestimate the importance of staying at home at this time.

21 April 2020

Your messages and words of support continue to warm my heart, and the feedback indicates that you want to learn of the reality at the front line– although it’s a war without weapons. Our doctor who worked in Afghanistan mentioned that he feels the “dramatic level of trauma” here is somehow worse than what he experienced out there, in that war zone.

This monster is worse? This Covid war has an unseen enemy, and our dwindling supply of PPE supposedly protects us. On Sunday I cared for a group of patients in a makeshift and cramped ICU on Brodie Ward: cables trailing along the ground, monitors balanced on top of ventilators, and the emergency oxygen supply for my patient was attached to the bed of another patient with rolls of green tubing that looked like a garden hose hanging off the end of the bed in this non-ICU.

The PPE is suffocating. It’s hot and tight. I have a cut above my left ear from the mask’s elastic. We have to shout, or we cannot be heard. At one point I felt an overwhelming desire to break free and rip it all off – to lift my visor up and breathe. My nose was blocked, my throat was sore. But then an alarm went off. A patient became unstable, and I was distracted.

This war requires resilience, stamina, and bravery. We are operating outside our normal systems. It takes time to be a skilled professional in the Critical Care setting, and suddenly we are catapulted into this strange and new space of Covid rage.

One man died. Aged 60 and, apart from being diabetic, he was a working husband and father. A junior nurse and I held his hands as he died. We spoke to him and I tucked into his hand the photo of him at his daughter’s wedding last summer. There were no curtains around his bed, no family with him. He was another Covid victim, snatched from life. The junior nurse had tears running down her face. “This is not how it is supposed to be,” she said. I spoke to his daughter on the phone. I could hear her pain as I tried – inadequately – to describe his final moments and to reassure her that her father was not alone when he died.

He had been sedated. It is hard for the patients who are conscious, as they cannot see our faces. I hope they can see us smile at them from behind our masks. We touch their face and hands so they feel safe, and we will do all we can to help them through this.

One patient I recognised and, at first, he refused to be ventilated, as he was scared. Now I am programming his ventilator, giving him medication as I look into his familiar face. Happily, he is doing well, and I hope will make a full recovery.

The walls are scarred from the beds and trolleys crashing into them

A patient who was ventilated for 21 days left Critical Care and had been proned for much of the time (nursed while lying on his stomach to improve oxygenation). As he was wheeled out, staff lined the corridors, clapping, and he smiled, waving his arms in victory. A fantastic moment that we shared: patient and NHS staff, united in success.

There is another patient with pink gel nails, whose nail growth demonstrates the passing of time. I am sure she would be horrified to see her nails this way.

We are shattered and do what we can to ensure that we all have space to shed a private tear, or have time out to eat and drink. Hospitals always seem to be designed with only a spare inch of space. The walls are scarred from the beds and trolleys crashing into them, but the genius who designed the Atkinson Morley Wing added a large balcony. There, we can eat hot lasagne provided by Critical NHS. It is welcome comfort food and, just for a moment, we sit on that balcony with our faces in the sun and feel like the world is normal again.

The grey, blue, green and white stainless-steel shades that we see are suddenly peppered with orange hedgehogs, purple stripes and polka-dot hair covers, sewn with love and donated by the wonderful community who support us. There is quite a fashion trend for the many nurses who look like Amish women with their hair covered by a cloth cap. The Trust tell us that these are not required as PPE.

It doesn’t matter: we love them, and we all wear them. One of the male runners wore a pink cap with dancing kangaroos on it.

I received a text from a Portuguese nurse: “I need some chocolate, a Coke and a new hair cover. Is there a pink one?” I was able to fulfil all three requests.

Claudia said, “The nurses are beautiful, hilarious, tireless heroes.”

I don’t know how this will end but we look forward to that day. I want to hug someone – that’s what I miss.

I did have to break protocol. I found one of our young nurses in the changing room, sobbing. I cuddled her as she cried, wondering what hideous thing she had just experienced. She calmed down and I held her tight. After a few minutes she simply said, “I miss my mum.”

Another young nurse cannot speak to her parents. “They’re scared for me, and I don’t want to make them more scared by telling them about the situation,” she said. “My father is my usual support system, but now, in all of this, I can’t talk to him.”

One nurse frequently stays late, after finishing her shift. Why? “I don’t want to go home. How crazy is it, not wanting to go home? But that’s how I feel. And when I go home, it’s to eat and shower and then come back to George’s. But I just want to stay here.” We finish a shift and find reasons not to leave because going home feels wrong. At home, we feel like we are in the wrong place.

For now, this is our normal. We are adjusting and have new protocols in place and a new way of working until we have won this war.

This truly fabulous team, created after an email from me requesting biscuits for nurses. Their ongoing support and the support of so many friends, neighbours and far-reaching community has been phenomenal and is supporting NHS staff through this war.

Life, Death and Biscuits by Anthea Allen (HarperCollins, £14.99) is out now.