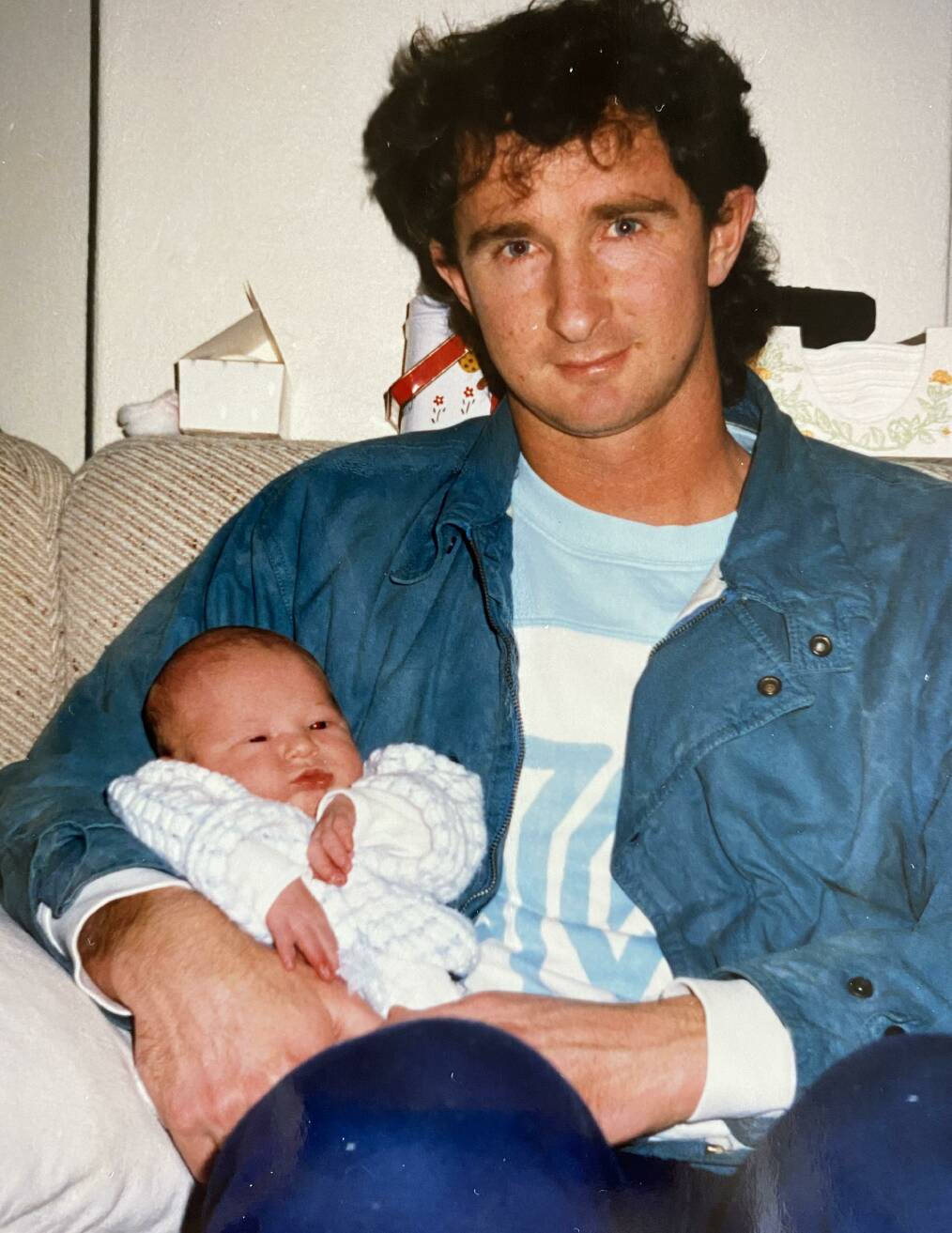

ALMOST 33 years ago, eight-week-old Beau Richards went to sleep, and he never woke up.

His parents - Mark and Jenny Richards - had never heard of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDs) until then. Their distress felt amplified because there was no explanation why this had happened to their baby boy.

There was no reason. There were no answers.

"I think it was the second year they'd had Red Nose Day, but we hadn't been aware of it," Mrs Richards told the Newcastle Herald.

"So when it happened, we were just at a complete loss as to why you can put a perfectly healthy child to bed, and they go to sleep, and they don't wake up... Our son was perfectly healthy in every way. He'd recently been to the pediatrician, and there was no indication of any problems at all. For us, it was like being hit over the head with a sledgehammer. It came so out of the blue, so suddenly."

Back then, there was limited information on SIDs, based on very little research.

Mark Richards was already a four-time world surfing champion, and his profile helped raise awareness of SIDs and the annual Red Nose fundraisers.

"We were in a fortunate situation with Mark's connection to the surfing world that we could do quite a lot to help raise funds for research for SIDs, and we did that for a number of years," Mrs Richards said.

"We always hoped something would come along, and that something would happen in terms of genuine research. One of the most difficult things - apart from all the grief that you're dealing with, was not knowing why, not having any answers."

Last week's news that Australian researchers have identified a "game changing" blood marker that could help identify babies at higher risk of SIDs has the potential to save thousands of lives and prevent a lifetime of anguish and heartbreak for their families. The crowd-funded research was led by Dr Carmel Harrington, who lost her own child to SIDs 29 years ago.

Mrs Richards said she hoped it provided SIDs families with the answers they craved, and reassurance that change was in motion to stop it happening to other babies.

"You question everything," Mrs Richards said. "The rational side of me said, 'This is not your fault, you've done nothing wrong'. But as a mother I questioned why I couldn't see it coming, whether I did something wrong."

Mrs Richards said they had been "incredibly blessed" to have three healthy children.

"But that doesn't take away the part of your life that you don't have anymore."

About 3000 babies and young children die "suddenly and unexpectedly" each year. Red Nose chief executive Keren Ludski, who lost her third son Ben to SIDs in 1998, said it had always been a "diagnosis of exclusion" - when a reason for the baby's death could not be found.

"You don't even know what the could'ves, should'ves, would'ves are, because you don't know what caused it," she said. "We say up to 60 people are impacted by the death of a baby. My son Ben's death shook my community, it shook my friendship circle, my family, my extended family, the school community, my professional connections. It rocks everything."

This research could help them determine was SIDs vulnerability looked like.

"As a SIDs mum, I sat reading the research summary findings with tears literally pouring down my face," she said. "SIDs parents, until the day they die, will have questions as to why their baby? To have even the sniff of an answer is game changing."

Professor Craig Pennell, a senior researcher at HMRI's Mothers and Babies Research Centre and chair of the National Scientific Advisory Group for Red Nose, said there had been no predictive tests that had shown any potential to identify children at risk of SIDs early in life, until now.

"At the moment there is no specific way families can prevent SIDs outside of the safe sleep messages - which have resulted in a dramatic reduction of SIDs in Australia," he said. "But to save more children, we need to be able to identify people at greatest risk and work out how to manage that."

Professor Pennell said it was already known that the autonomic nervous system (which regulates how all of the important body functions - such as breathing - work) was involved in the mechanisms of SIDs.

"The next step has been how you could pick that up at birth to look at a prevention program," he said.

"This blood marker that has been identified could be assessed at the new born blood screening that's done with the heel prick test."