Jessica Treviño’s 11-year-old daughter was attending Robb Elementary School on May 24, when a gunman fatally shot 19 children and two teachers. She was not physically hurt. But in the nearly two months since, she has suffered from anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder — conditions that have required up to $1,500 a week in physical and emotional care.

The Treviños currently qualify for some of the millions of dollars that have been raised to help shooting victims and survivors — but they haven't seen any of it yet. Such funds normally take months to administer and distribute. That reality has not been conveyed effectively, however, to families in dire need of help now.

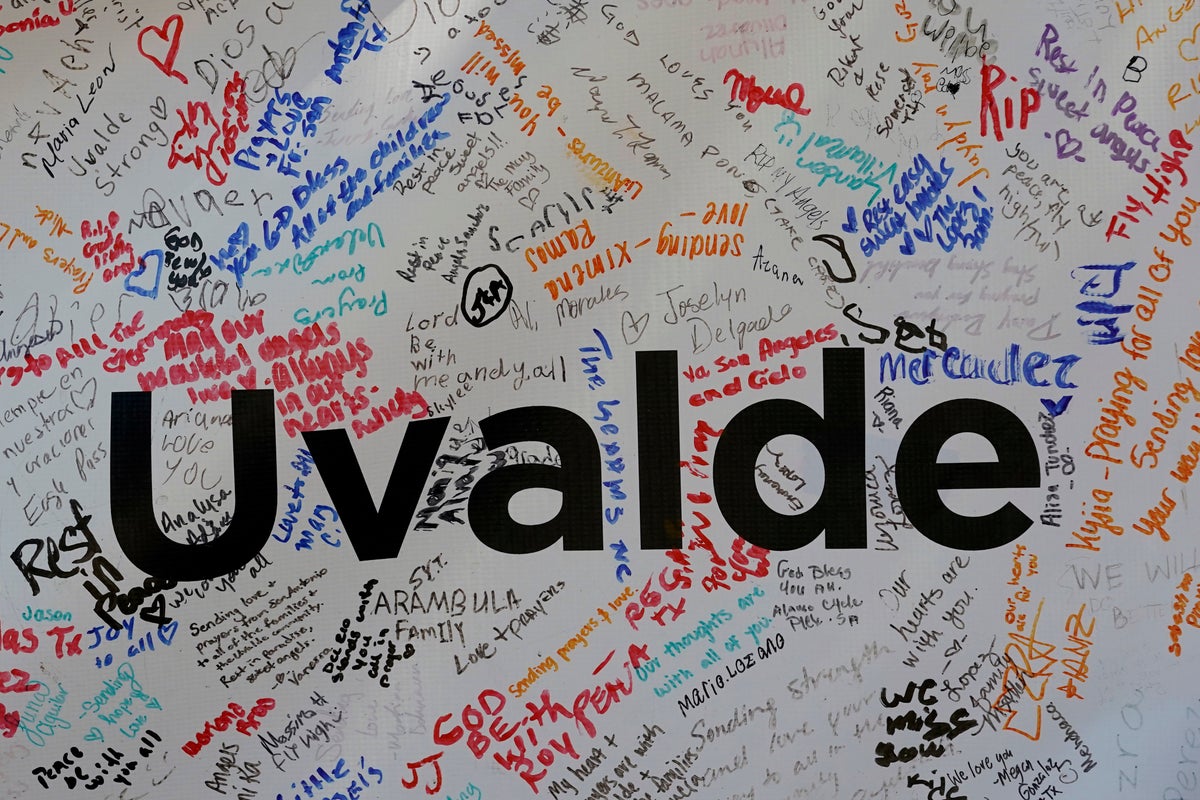

During a packed city council meeting in Uvalde on Tuesday, multiple people shouted out questions from their seats about why financial relief seemed to be taking so long. City leaders have offered little clarity — and seemed to be just as confused.

“These families cannot begin to heal unless they are given time to grieve free from financial worry,” Uvalde Mayor Don McLaughlin and state Sen. Roland Gutierrez stated in a letter sent last week to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott. The mayor and lawmaker said they had both received “numerous troubling reports” of people receiving insufficient financial resources aside from a two weeks' bereavement benefit. They cited one family that was struggling to keep the lights on while a child was hospitalized.

At least $14 million has been raised in private and corporate donations for families affected by the shooting. All have been combined in the Uvalde Together We Rise fund, which will be administered by a local steering committee with guidance from national experts.

But creating a plan to ensure that the funds are distributed equitably and transparently takes time — usually months, noted Jeffery Dion, executive director of the National Compassion Fund. The nonprofit organization has helped distribute more than $105 million in donations for people affected by 23 other mass casualty incidents since 2014. Among them: mass shootings at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, in 2016; at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in 2018; and at a Walmart in El Paso in 2019. In each of these cases, donations took multiple months to get to victims.

“It’s a gift, so there is no right or wrong answer, but the most important thing is that it is the local answer,” Dion said, adding that each local steering committee ultimately has the final say on the distribution plan.

Currently, funds are expected to be distributed to families starting Nov. 21, according to Mickey Gerdes, a local attorney who chairs the Uvalde committee in charge of donation allocation. Gerdes said a draft of the distribution plan is currently available to the community and will be finalized after public input.

In the meantime, the Treviños and many others have started GoFundMe pages and multiple donors and organizations have stepped in to provide immediate financial relief.

The Uvalde Volunteer Fire Department has written checks directly to 15 families of the injured, according to department president Patrick Williams. He said the organization initially received $21,000 through an annual fundraiser, which it decided to dedicate to the victims, and $49,000 through a related GoFundMe page, which closed June 1.

“At no point in time should we be talking about money and the loss of children’s life in the same sentence, but here we are and it has to be talked about,” Williams said, noting that the money his department has raised is helping families of the injured who have had to miss work and who are struggling with medical and everyday expenses.

“This has shown me the worst in man and the best in man,” Williams said.

The Treviño family’s GoFundMe page has raised more than $47,000. But, Jessica Treviño said traveling to San Antonio on a weekly basis for treatment while providing for her three other children is still a financial challenge for her and her husband.

“I also think that a lot of mental illness is pushed aside because of families like my own who have no help financially,” Trevino said.

Distributing the $14 million that is available through the other sources takes so long because each application must be vetted through medical and law records, according to Dion. He said families also need time to consult with pro-bono attorneys who can advise them about the best way the funds can be transferred — especially to minors — in accordance with local laws and without them losing any other public benefits they may already be receiving.

Applications to receive funds will be available online between Sept. 8 and Oct. 6. According to the current draft of the distribution plan, those eligible include legal heirs of the deceased, those who were either physically hurt or experienced psychological trauma, and students and staff who were present at the school when the shooting took place.