UVALDE, Texas — Before the tragedy that ripped a ragged hole in the heart of this town, any fame it had accumulated came by way of its honey hives, a Tejano band, a vice president, governor, even the Queen of the West. A state football title didn’t quite pull the same rank locally. Didn’t even rate a mention on the water tower looming high above the Honey Bowl.

But 50 years after the Uvalde Coyotes’ greatest glory and four months since the source of their deepest sorrow, the hope here is that a reunion celebration on Labor Day weekend will provide at least a brief respite from grief.

Maybe even helps a community begin to heal.

Steve Stoy knows how improbable it seems, that recycling memories of the 1972 football season might somehow mitigate some of the pain, anger and bitterness coursing through his hometown. Nothing heals the loss of 21 lives. No one dare suggests it could. Certainly not anyone who sees the reminders daily. Stoy and a half-dozen of his former high school teammates still live in the town where they grew up. They worship at the same churches as the victims’ families, shop at the same grocery stores, eat in the same restaurants.

Drive past the same memorials.

The ‘72 Coyotes were so sensitive to the grief and outrage since the shootings at Robb Elementary on May 24, they weren’t even sure they should go ahead with the reunion. They didn’t know if it’d be right. They’re not sure of a lot of things these days.

“Nobody knows what to do,” said Stoy, a retired farmer, “because you’ve never been in a situation like this.

“Once you’re in it, it’s miserable.”

Now that they’re all in it together — a tragedy in a town of 16,000 touches nearly everyone — they’ve been humbled by the kindness of outsiders. More than $14 million in private donations and $6.5 million from the state for mental health services. Bo Jackson, a legend in two sports, wrote a check for the funerals. Houston Astros officials chartered 10 buses to take 500 citizens to Houston and passed out 3,000 tickets for “Uvalde Strong Day” at Minute Maid Park.

Next to the grand gestures, the smaller ones still stand tall. Visitors dressed up as superheroes for the kids. Petting horses. Healing dogs. So many toys, Uvalde officials asked that donors cease and desist. They had no place for all of them.

Jill Stoy, Steve’s wife and a Uvalde cheerleader in ‘72, marveled at the generosity from so many outside their community who figured even a letter of sympathy could help. She resolved that, given their heartfelt responses, the reunion offered an opportunity to do no less.

“This is something we did,” Jill said. “We get to remember and celebrate.

“We get to bring this in.”

‘Look ‘em in the eyes’

Over the last hundred years or so, Uvalde hasn’t been nearly as good at football as it’s been at producing celebrities, as depicted in a mural on the side of the Rexall building. John Nance Garner, twice Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate, the man who famously said occupying the office of vice president “was not worth a warm bucket of spit,” or something along those lines, hailed from Uvalde. So did Dolph Briscoe, governor of Texas from 1973-79, and Dale Evans, the actress, singer and wife of Roy Rogers. Matthew McConaughey, duly claimed by Longview, got his start in Uvalde, as did the Grammy-winning Tejano group, Los Palominos.

Uvalde football, on the other hand, isn’t so much starry as star-crossed. Only four times — 1935, 1949, 1972 and 1988 — has it advanced past regionals. When Marvin Gustafson arrived from Devine in 1965, Uvalde was coming off a three-year drought in which it had won a total of four games. When Gustafson, big brother of Texas’ Hall of Fame baseball coach, Cliff, won eight games his first season, a legend was born.

The men who played or worked for Coach Gus — as it says even on his headstone — will tell you he was neither a martinet nor a glad-hander. He didn’t rule by intimidation, but he brooked no foolishness, earning universal respect in the process. His assistants weren’t immune to reproach, and what a staff it was. Two members have high school stadiums in San Antonio named after them. One for Gustafson; the other, his top assistant, Jerry Comalander.

“He taught me to look ‘em in the eyes, don’t waste their time at practice and do your best as a coach to get the team to play hard every play,” Comalander recently told the Uvalde Leader-News. “I spent 12 years with him and learned something every year.”

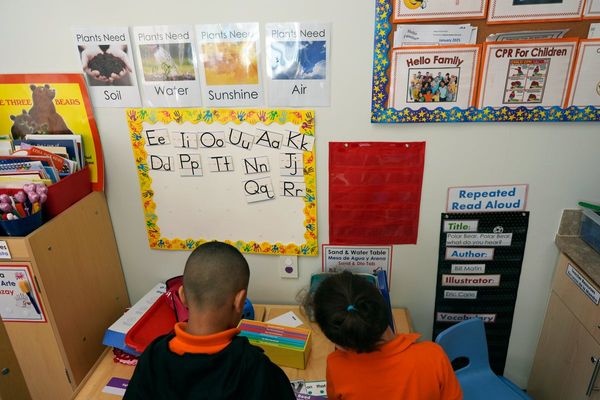

At Uvalde, Gustafson installed a system grounded in the T-formation and a stout defense that started with the sixth-grade flag football teams at the town’s elementary school programs. By the time Stoy and his teammates got to high school, it was all rote.

Gustafson filled in any gaps.

“He could get you to play,” Stoy said, his eyes suddenly red-rimmed.

Going into the ‘72 season, the Coyotes were consensus picks to win Class 3A, then the state’s second-largest classification. The belief was based on the Coyotes’ first district title in 15 years the season before; the quality of the returning lettermen; and the addition of quarterback Lynn Leonard, who’d moved in from Crystal City.

Uvalde rewarded the show of faith. Of its 15 games, seven were shutouts. Going into the semifinals against Brenham, the Coyotes had outscored opponents 511-38. Even more impressive was the fact that, most games, the starters didn’t play after halftime. They still piled up numbers. Stoy and Oscar Mireles, the halfbacks, combined for 1,992 yards, and Mike Paradeaux, the fullback, put up another 773. Randy Gerdes, the tight end, caught 39 passes for 650 yards and made first-team All-State, as did Ronnie Rogers, who lined up next to him at left tackle, and Mike Bingham, the left guard.

The more they won, the deeper their run, the bigger the buzz.

“You’d go to the gas station, and they’re talking about it,” Jill Stoy said. “You walk in the bank, and they’re talking about it. That was the thing that stayed with me so much at the time.

“As a 16-year-old girl, I remember thinking, ‘This is the neatest thing for our town ever.’ ”

Before Uvalde met No. 2 Brenham in the semifinals at Texas’ Memorial Stadium in a matchup of No. 1 vs. No. 2, Gustafson bused his team nearly three hours to Austin for practice. He wanted to give them a feel for playing in a stadium 10 times bigger than what they were used to. He needn’t have worried about the size of the venue; Brenham was a big enough problem.

Fronted by mammoth defensive tackle Wilson Whitley, who, at Houston, would be named the Southwest Conference’s Defensive Player of the ‘70s, the Cubs’ defense played the Coyotes’ formidable offense to a 21-21 standstill through three quarters.

And it was at that point that Uvalde pulled one of the most famous switcheroos in state playoff history.

The guard special

The “guard around” or “guard special” had been a staple in Gustafson’s playbook since Pettus used it against him when he was at Devine. He’d tried it three weeks earlier against Cuero, but it went for no gain. Gustafson wasn’t really big on trick plays, figuring that you won with good, fundamental football. Against Brenham, the proposition didn’t appear to be enough.

“We were just an average bunch of kids, no stars, well-coached,” Gerdes said. “Brenham was big, strong and aggressive.

“They should have killed us.”

Had it not been for the guard special, the Cubs might have obliged. The play called for the quarterback to pretend to take the snap, turn and fake a hand-off to one of his running backs. Only the quarterback never really had the ball. The center would retract his offer and place the ball on the ground near the right guard, who’d cover it up while taking care not to touch it, lest the play be ruled dead. Then he’d count to himself.

One thousand one . . . one thousand two . . .

One thousand three!

And off he’d go.

In Gustafson’s version of a play commonly called a fumblerooski, sleight-of-hand was only half the trick. No matter how well executed, it served no purpose for a big lug of an offensive lineman to end up with the ball. Basically, you needed someone fast to make it work. Which is how Richard Sanchez, who’d often boasted about how his speed, found himself the centerpiece of the biggest play in Uvalde football history.

On the sideline, Gustafson told Sanchez, normally a defensive end, to get ready for the guard special. Behind a ring of teammates serving as a makeshift screen from the Brenham coaches and players, Sanchez changed jerseys with Kenneth Carter, a back-up offensive lineman. Leonard then told the referee the play they were about to run, averting a potential whistle or flag that might foul up everything.

Once the play was in motion, Sanchez did just as he’d practiced dozens and dozens of times. Cover the ball. Count.

Run.

“When I bellied around and saw all that open space,” he said, “I thought, ‘Wow.’ ”

Nothing between him and six points except three All-State linemen and 69 yards of Memorial Stadium grass.

It was the only time Gustafson’s guard special had ever resulted in a touchdown.

The play not only fooled the Cubs — Whitley tackled at least two Coyotes looking for the ball — it bamboozled Uvalde fans as well.

Watching the play unfold, Jill Story thought, “Why is Richard wearing Kenneth Carter’s jersey?”

Brenham’s coach, Lloyd Wassermann, thought the same and protested loudly, to no avail. The play not only gave Uvalde a 27-21 lead, it sucked the air out of the Cubs and gave the Coyotes back-to-back weekend trips to Austin.

The championship game the next week against Lewisville proved to be no easier task than the semis. Comalander, who would follow Gustafson the next year to San Antonio Churchill, where he’d win a state title in ‘76 as head coach, considered Lewisville’s Paul Rice one of the three greatest high school running backs he ever saw. He wasn’t the only one impressed. Before the title game, Gordon Wood, king of Texas high school football coaches, told Charley Robinson — a former Uvalde assistant who went on to broadcast games of the teams he once coached — that Rice would run for 400 yards against the Coyotes.

“He was wrong,” Robinson said, grinning. “He only went for 290.”

But in the fourth quarter, with Uvalde ahead 33-28 as Lewisville crept to within five yards of the lead, three straight carries by Rice netted but three yards. No trick plays would be needed. The Coyotes had their one-and-only state football title.

“Boys,” Gustafson told his Coyotes on the bus back home, “this is something you’ll remember your whole life.”

The benefits for Richard Sanchez were slightly more tangible. For years after his famous romp, he never had to pay for a haircut.

They too will live

In the square where Uvalde fans once celebrated one of the greatest moments in the town’s history, 22 wooden crosses, each about four feet tall, ring a fountain shaded by ancient pecan trees. On each cross, there is picture after picture after picture of sweet, smiling faces. A similar memorial sits across town at Robb Elementary, now boarded up, fenced off and guarded by a lone state trooper. Visitors from near and far leave flowers, balls, stuffed animals, wishes, prayers and poems.

"As long as we live, they too will live;

For now they are a part of us,

As we remember them"

Jill Story says she often finds herself driving past Robb Elementary for no reason.

“I can’t quit,” she said. “I have friends who say they can’t drive by it.”

“I can’t, either,” Steve said. “I cannot. Just thinking about it ... "

His voice trailed off.

“It’s terrible.”

All three of the Stoys’ daughters and their families live in Uvalde. One of their 11 grandchildren, Gina Gatto, played on the same softball team with one of the victims, Makenna Elrod. From behind on the field, it was difficult to tell them apart. They attended the same birthday party a few weeks before the shootings. Played a softball game only a couple days before.

The softball team went to the funeral in their uniforms. Gina presented flowers to Makenna’s parents.

How did your granddaughter deal with it?

“Very quietly,” Steve said.

Everyone in Uvalde interviewed for this story had some sort of personal tie to the tragedy. Wade Miller, now going into his second season as football coach and athletic director, said two of his players lost siblings. A few came to him for counseling. When summer workouts started with 25 more kids than turned out last year, Miller issued a statement that the No. 21 jersey, representing the victims, would go to a senior “who represents everything Coyote football and the city of Uvalde stands for. Hard work, loyalty and the love of this great community. So when you see a kid with the number 21 on the field in a Coyote uniform, know he represents us all and has earned the honor of wearing this number!!!”

Steve Stoy’s number was 21.

“It’s a special number now,” Jill said.

Of the ties to people in this story, Oscar Mireles’ was the closest. Eva Mireles, one of the slain teachers, was a third cousin. Lexi Rubio, a fourth grader, was also related. Which is probably why, when asked if the shootings and the state title were the two biggest stories in the history of Uvalde, Mireles bristled and said, “You don’t want to put that in that category.”

Mireles and Gerdes sat in the shade of the Honey Bowl press box recently as they talked about their team and town.

Occasionally they interrupted each other, as old friends do.

Gerdes played three years at Texas; Mireles, at Texas Lutheran. They ruminated on how football wasn’t the same after high school; what’s been wrong with Uvalde’s football program ever since; who’s coming back for the reunion; and their hopes for what a renewed interest in the state title might do for the spirits of their beleaguered town.

They also talked about how the 5,000-seat Honey Bowl — with its Bermuda grass field and border of saltcedar — remains one of the few places in Uvalde that hasn’t changed much in the last 50 years. Other than a fancy new scoreboard, a regulation track and aluminum bleachers, everything else is pretty much the same.

They take some comfort in that kind of consistency, given what they lost in May.

“That stuff happens in big cities,” Gerdes said. “You don’t ever think about that happening in a little bitty community.”

They stared out over their old football field a good 15 seconds in silence, or what seemed like a prayer.