Africans normally pay little attention to American elections when the presidency is not at stake. But the midterm polls – such as the 8 November 2022 one – deserve Africa’s attention.

During midterms, US voters elect 435 members of the House of Representatives for a two-year term and one-third of the senators, the 100-member upper house, who serve for six years. The two houses are collectively known as the US Congress. Some governors, and other officials, including those responsible for elections of the 50 states, also seek a mandate during this period.

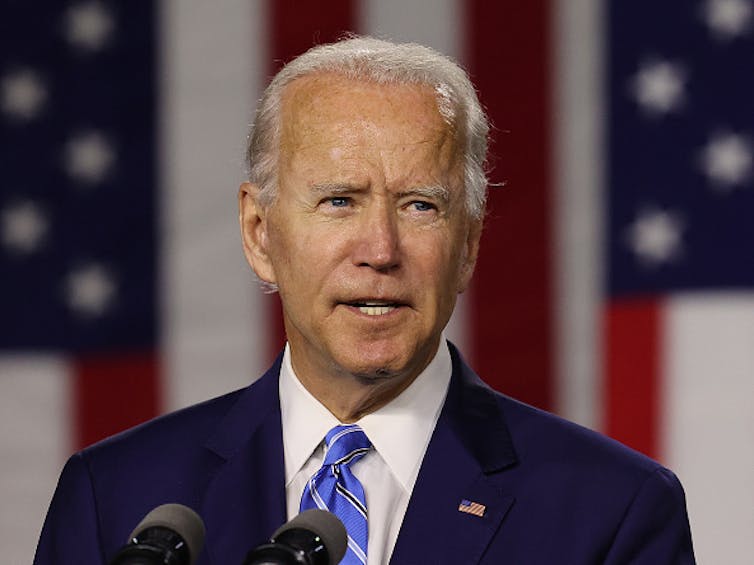

Midterm elections take place halfway into the president’s term of office. Typically, they are taken as a judgement on his performance. President Joe Biden’s national approval rating on the day before the midterms was only 39%. This suggested there would be another big win for the opposition Republicans. Instead, the Senate remains narrowly Democratic and the House likely will have a slim Republican majority when all votes are finally counted.

America is still deeply divided. I believe, however, that the electioneering showed democracy’s resilience, which should be a boost for democracy advocates across Africa.

The “wild card” in this election was the role of Donald Trump. He and his supporters managed to get their candidates nominated in many states. Most promoted his false claim that the 2020 presidential election had been “stolen” and Biden was an illegitimate president. They also favoured the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn a woman’s right to an abortion. Both issues, electoral integrity and human rights, are of concern to democrats everywhere, including Africa.

Foreign policy was not an issue

Voters understand that foreign policy is rarely an issue in midterm elections. Presidents retain wide discretion in foreign policy.

Current US strategy towards sub-Saharan Africa will continue to frame US foreign policy at least until 20 January 2025, when the next administration is inaugurated. But African governments and their citizens have many other interests and values at stake in relations with America.

What matters to African countries are the social forces at work in the US that may affect the long term relations between the US and Africa. America is becoming more pluralistic. The African diaspora is becoming more integrated. A backlash from those Whites fearful of losing status seems inevitable. Whether and how Americans manage this peacefully and democratically should interest the world’s most diverse continent.

I recall, for example, how the Black Lives Matter campaign resonated across Africa.

The Trump factor

The foremost US domestic issue that should concern Africa is whether Donald Trump’s role in shaping this election will affect his own prospects of reelection in 2024. Many of his supporters ran, and many of them lost. This could reduce his chance to be the Republican nominee in 2024.

Three aspects of these hotly contested races that are salient for sustainable democracy in Africa are already clear.

First, in highly polarised but diverse societies, close elections are to be expected, and demand nonviolent and just democratic discipline.

Second, electoral integrity matters and must be transparent and authoritative. Citizens need to be confident that all their votes will be counted. Trump and his allies denigrated the certified electoral results in 2020 and the accuracy of voting last week. But voting in all 50 states went off with very few glitches.

Third, candidates must “play by the rules”. The most important of which is to concede when informed by election officials that you have lost. If candidates fail to do this, the risk of violence becomes acute, as it did in the assault on the US Capitol by Trump supporters on 6 January 2021. Voters in the midterms showed that they rejected “electoral denialism” without proof.

A divisive but decisive issue that motivated high turnout in several US several swing states was whether women have a human right to decide for themselves whether to have an abortion, within democratically agreed rules.

Read more: How US policy on abortion affects women in Africa

Many other democracies, including South Africa, constitutionally guarantee this right. Republicans have long imposed abortion restrictions on women’s health programmes sponsored by the US Agency for International Development. During the Obama Administration they were removed, but Trump reimposed them.

US elections and the world

The 2022 US midterm election at least offers hope that constitutional or civic nationalism – not white racial nationalism – will define US democracy. The country is demographically becoming more ethnically diverse, in that sense more like Africa.

America has a large and growing African diaspora. According to exit polls, eight in 10 black Americans voted for Democratic candidates in the 2022 midterm election, although Republicans are making some inroads. Many are recent immigrants from Africa who continue to maintain close family and cultural ties to their countries of origin.

African scholars and diplomats could learn important lessons from their diaspora’s hopes and fears about America’s version of democracy and federal system.

Mutual learning

All African governments are collectively committed to basic democratic principles under the Constitutive Act of the African Union and the African Charter for Democracy, Elections, and Governance.

The United States, the world’s oldest democratic experiment, remains vulnerable to a populist demagogue, determined to defy the first principle of sustainable democracy: the peaceful transition of power. This alone should give African scholars incentives to learn more about the internal workings of American politics and why and how this principle showed resilience in the 2022 midterm poll.

This could inform their debates about which version of democracy is best for their nation, and might even yield fresh insights of value to American democrats as they strive to fulfil their constitution’s promise to “form a more perfect union”.

John J Stremlau does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.