Since Iron Man hit the big screen in 2008, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) has made more than US$30 billion, from films to series, to merchandise and comics. As scholars and the press have noted, key to its success is the use of a highly gripping and elaborate “shared universe”.

A number of shared universes have popped up since the MCU, including Legendary Pictures’ MonsterVerse (featuring Godzilla and King Kong), James Wan’s Conjuring universe, the Star Wars universe and the rebooted DC Universe.

You might be surprised to hear they’ve actually been around for a very long time – but most of them fail to really get off the ground.

What is a shared universe?

The definition of a “shared universe” is a bit tricky to pin down, as it overlaps heavily with related concepts such as spin-offs, crossovers and franchises.

At its simplest, you can think of a shared universe as a narrative world made up of at least two texts (such as film, television, video games or books) that are distinct, but with overlapping narrative elements.

The texts may have different main characters, different stories, or even different settings – but there will be, at the minimum, some evidence they take place within the same broader world.

Early shared universes

Shared universes have been a staple in storytelling since the dawn of mass media – and not just in cinema.

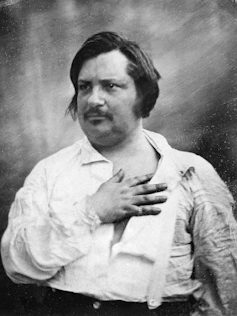

One of the first shared universes was The Human Comedy (La Comédie humaine) series (1829–48) by French novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac.

Set against the French Restoration, following the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte, Balzac’s sprawling world spans more than 90 novels and charts the complexity of post-revolution life.

Another early example from literature is L. Frank Baum’s Oz universe. After Baum grew tired of the Oz books, he wrote The Sea Faeries (1911) as the start of a new series. Its lack of critical reception forced him to return to Oz, but not before bringing some Sea Faerie characters along to the Oz universe with him.

The shared universe trend continued in the early 1900s with writers such as Isaac Asimov, Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft, and would become a mainstay in sci-fi and fantasy.

However, it was arguably television that made shared universes mainstream. This started as early as the 1960s with The Danny Thomas Show and its spin-off The Andy Griffith Show. Other notable examples include the Cheers spin-offs, the Law & Order franchise and the Vampire Diaries universe.

Television’s episodic form – perpetually stuck in the second act – lends itself to spin-offs. Why risk time and money on something new when a fan-favourite character can get their own show, with the prestablished audience (hopefully) migrating over?

Before Marvel came thundering along

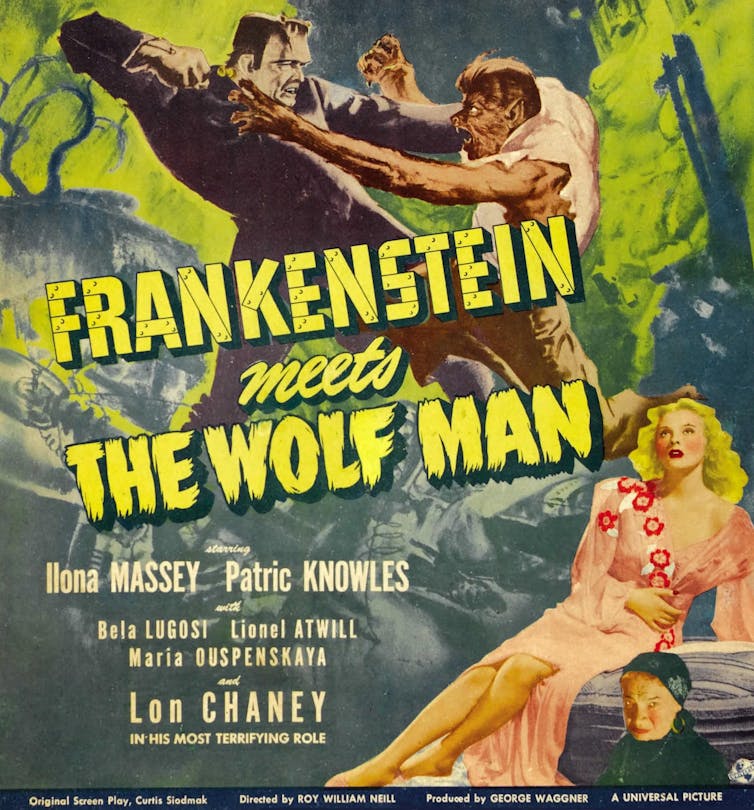

One of the earliest cinematic universes was Universal’s original Monsters franchise, beginning in 1931 with the films Dracula and Frankenstein.

This universe was made up of horror characters including Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster and the Wolf Man. Crossover offerings included Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) and House of Frankenstein (1944).

But this attempt at a coherent world was haphazard. Continuity was often ignored or contradicted, with post-editing decisions cutting out crucial story connectivity.

For example, in The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Ygor’s brain transplant is what allows the monster to speak, yet this element is omitted from later films.

Difficult beginnings

Only a handful of cinematic universes have been truly successful. Following the MCU’s triumph, Warner Bros. attempted a King Arthur universe with King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017), but it flopped.

Sony then tried (and failed) to begin a franchise with Robin Hood (2018) that would spin off to his many merry men.

And it would be remiss to not mention Univeral’s attempt at recapturing its original Monster universe with Tom Cruise’s The Mummy (2017). This film was supposed to be the beginning of the so-called “Dark Universe” which – you guessed it – never happened.

The trifecta you need for success

One cultural character with great success in cinematic universes is Godzilla. The radioactive reptile has been a hit in two separate shared universes: first in Toho Studios’ Japanese live action films, and more recently in Legendary Pictures’ MonsterVerse.

The latter has grossed more than US$2 billion worldwide, and given us five major films including Godzilla (2014) and Kong: Skull Island (2017), as well as two spin-off shows that have begun production on their second seasons.

An experienced screenwriter explained what makes a successful franchise to media scholar Henry Jenkins:

When I first started, you would pitch a story because without a good story, you didn’t really have a film. Later, once sequels started to take off, you pitched a character because a good character could support multiple stories. And now, you pitch a world because a world can support multiple characters and multiple stories across multiple media.

It is the trifecta of story, characters and world that gives rise to a successful shared universe. And the MCU and MonsterVerse both provide captivating worlds in which more characters and stories can always be added.

Marvel films are by no means groundbreaking, as they follow the typical heroes journey of good versus evil. But they leverage comic book characters that had already captivated fans through a different medium.

Also, the MCU was meticulously planned from the beginning: one universe populated with several heroes was always the endgame. As a result, Marvel has managed to transform C- and D-list superheroes into household names.

Meanwhile, the MonsterVerse draws audiences in with the sheer spectacle of massive titans – who were also already well-known – engaging in action-packed battles.

In both cases, there are always more heroes to appear, and more titans to fight.

So, can we expect major studios to continue to try and capture lighting in a bottle, like Disney has with the MCU? Unequivocally, yes. But what might change is the approach.

Failed cinematic universe attempts from the past had many reasons for failing – whether it was media constraints, or trying to capitalise on the hype instead of actually delivering a compelling fictional world. Creators of the future have a higher bar to meet.

Vincent Tran does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.