The U.S. citizenship test is being updated, and some immigrants and advocates worry the changes will hurt test-takers with lower levels of English proficiency.

The naturalization test is one of the final steps toward citizenship — a monthslong process that requires legal permanent residency for years before applying.

Many are still shaken after former Republican President Donald Trump’s administration changed the test in 2020, making it longer and more difficult to pass. Within months, Democratic President Joe Biden took office and signed an executive order aimed at eliminating barriers to citizenship. In that spirit, the citizenship test was changed back to its previous version, which was last updated in 2008.

In December, U.S. authorities said the test was due for an update after 15 years. The new version is expected late next year.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services proposes that the new test adds a speaking section to assess English skills. An officer would show photos of ordinary scenarios – like daily activities, weather or food – and ask the applicant to verbally describe the photos.

In the current test, an officer evaluates speaking ability during the naturalization interview by asking personal questions the applicant has already answered in the naturalization paperwork.

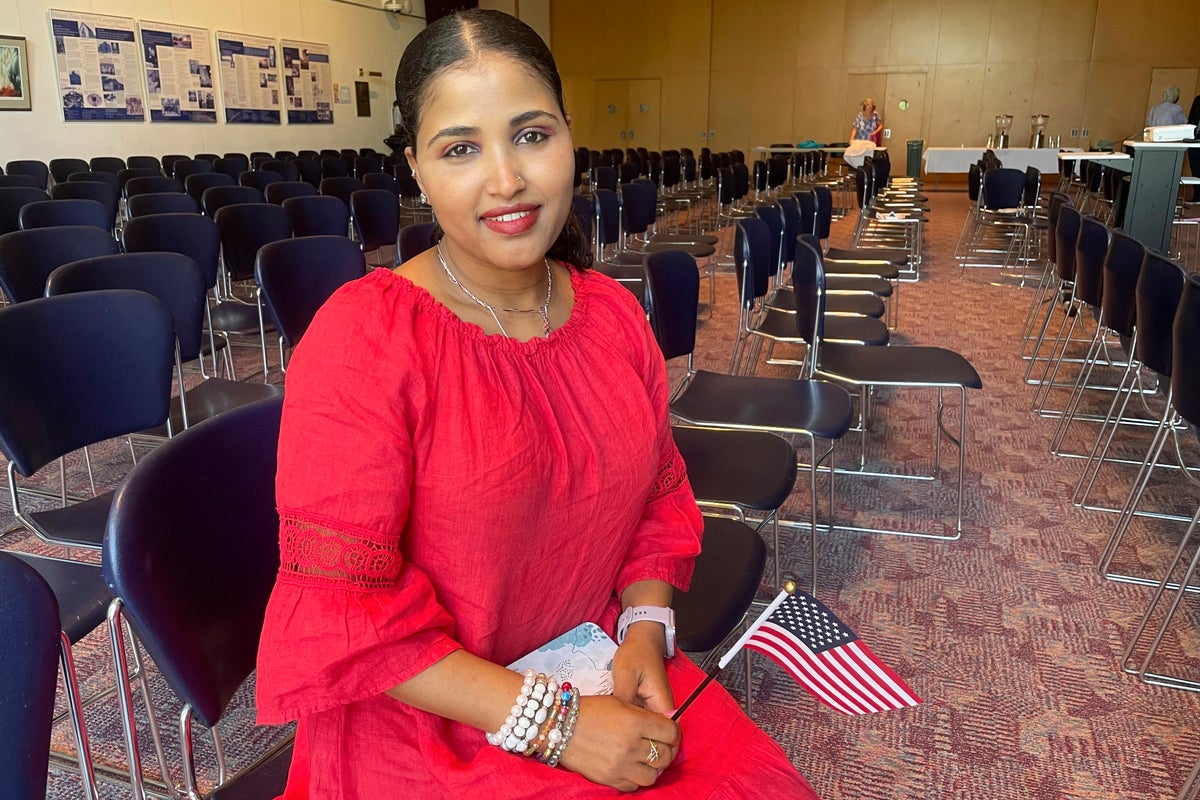

“For me, I think it would be harder to look at pictures and explain them,” said Heaven Mehreta, who immigrated from Ethiopia 10 years ago, passed the naturalization test in May and became a U.S. citizen in Minnesota in June.

Mehreta, 32, said she learned English as an adult after moving to the U.S. and found pronunciation to be very difficult. She worries that adding a new speaking section based on photos, rather than personal questions, will make the test harder for others like her.

Shai Avny, who immigrated from Israel five years ago and became a U.S. citizen last year, said the new speaking section could also increase the stress applicants already feel during the test.

“Sitting next to someone from the federal government, it can be intimidating to talk and speak with them. Some people have this fear anyway. When it’s not your first language, it can be even more difficult. Maybe you will be nervous and you won’t find the words to tell them what you need to describe,” Avny said. “It’s a test that will determine if you are going to be a citizen. So there is a lot to lose.”

Another proposed change would make the civics section on U.S. history and government multiple-choice instead of the current oral short-answer format.

Bill Bliss, a citizenship textbook author in Massachusetts, gave an example in a blog post of how the test would become more difficult because it would require a larger base of knowledge.

A current civics question has an officer asking the applicant to name a war fought by the U.S. in the 1900s. The applicant only needs to say one out of five acceptable answers – World War I, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War or Gulf War – to get the question right.

But in the proposed multiple-choice format, the applicant would read that question and select the correct answer from the following choices:

A. Civil War

B. Mexican-American War

C. Korean War

D. Spanish-American War

The applicant must know all five of the wars fought by the U.S. in the 1900s in order to select the one correct answer, Bliss said, and that requires a “significantly higher level of language proficiency and test-taking skill.”

Currently, the applicant must answer six out of 10 civics questions correctly to pass. Those 10 questions are selected from a bank of 100 civics questions. The applicant is not told which questions will be selected but can see and study the 100 questions before taking the test.

Lynne Weintraub, a citizenship coordinator at Jones Library’s English as a Second Language Center in Massachusetts, said the proposed format for the civics section could make the citizenship test harder for people who struggle with English literacy. That includes refugees, elderly immigrants and people with disabilities that interfere with their test performance.

“We have a lot of students that are refugees, and they’re coming from war-torn countries where maybe they didn’t have a chance to complete school or even go to school,” said Mechelle Perrott, a citizenship coordinator at San Diego Community College District’s College of Continuing Education in California.

“It’s more difficult learning to read and write if you don’t know how to do that in your first language. That’s my main concern about the multiple-choice test; it’s a lot of reading,” Perrott said.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said in a December announcement that the proposed changes “reflect current best practices in test design” and would help standardize the citizenship test.

Under federal law, most applicants seeking citizenship must demonstrate an understanding of the English language – including an ability to speak, read and write words in ordinary usage – and demonstrate knowledge of U.S. history and government.

The agency said it will conduct a nationwide trial of the proposed changes in 2023 with opportunities for public feedback. Then, an external group of experts — in the fields of language acquisition, civics and test development — will review the results of the trial and recommend ways to best implement the proposed changes, which could take effect late next year.

More than 1 million people became U.S. citizens in fiscal year 2022 — one of the highest numbers on record since 1907, the earliest year with available data — and USCIS reduced the huge backlog of naturalization applications by over 60% compared to the year before, according to a USCIS report also released in December.