Taipei, Taiwan – During a five-hour grilling of the chief executive of TikTok last week, United States lawmakers railed against the possibility of China using the wildly popular, partly Chinese-owned app to spy on Americans.

They did not mention how the US government itself uses US tech companies that effectively control the global internet to spy on everyone else.

As the US considers banning the short video app used by more than 150 million Americans, lawmakers are also weighing the renewal of powers that force firms like Google, Meta and Apple to facilitate untrammelled spying on non-US citizens located overseas.

Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), which the US Congress must vote to reauthorise by December to prevent it from lapsing under a sunset clause, allows US intelligence agencies to carry out warrantless spying on foreigners’ email, phone and other online communications.

While US citizens have some protections against warrantless searches under the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution, the US government has maintained that these rights do not extend to foreigners overseas, giving agencies such as the National Security Agency (NSA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) practically free rein to snoop on their communications.

Information may also be turned over to US allies like the United Kingdom and Australia.

Though it is common for governments to spy abroad, Washington enjoys an advantage not shared by other countries: jurisdiction over the handful of companies that effectively run the modern internet, including Google, Meta, Amazon and Microsoft.

For billions of internet users outside the US, the lack of privacy mirrors the alleged threat that US officials say TikTok, owned by Chinese company ByteDance, poses to Americans.

“It is a case of ‘rules for thee but not for me,'” Asher Wolf, a tech researcher and privacy advocate based in Melbourne, Australia, told Al Jazeera.

“So the noise the Americans are making about TikTok must be seen less as a sincere desire to protect citizens from surveillance and influence operations, and more as an attempt to ring-fence and consolidate national control over social media,” Wolf added.

US President Joe Biden’s administration is pushing for both the power to ban TikTok and the renewal of Section 702, which it has described as an “invaluable tool that continues to protect Americans every day”.

Despite Tiktok’s efforts to assuage national security and privacy fears, including working with US tech giant Oracle to store American data on US soil in a $1.5bn initiative known as “Project Texas”, a ban or forced sale of ByteDance’s stake appears increasingly likely amid growing bipartisan antipathy toward the app in Congress.

In an appearance before Congress on Thursday, TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew failed to satisfy both Republicans and Democrats with his answers to a barrage of questions about data privacy and national security concerns stemming from a Chinese law that requires local companies to “support, assist and cooperate with the state intelligence work”.

Over the weekend, US House of Representatives Speaker Kevin McCarthy, a Republican, said his colleagues “will begin moving forward with legislation to protect Americans from the technological tentacles of the Chinese Communist Party.”

The app has already been banned on US government devices, as well as official devices in countries including Canada, Belgium, Denmark, and New Zealand, although an outright ban is seen as more legally fraught due to possible conflict with the First Amendment of the constitution that safeguards free speech.

Amid the growing chorus of voices casting TikTok as a threat, the privacy rights of non-Americans have received little mention.

In a recent article about the reauthorisation of Section 702, The New York Times described non-US citizens’ privacy as having “played little meaningful role” in the debate.

In 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, the US targeted 232,432 “non-US persons” for surveillance, according to government data.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) estimates that the US government has collected more than one billion communications per year since 2011, based on how the number of targets has grown since that year.

“They’re making a big stink about TikTok and the Chinese collecting data when the US is collecting a great deal of data itself,” Jonathan Hafetz, an expert on US constitutional law and national security at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, told Al Jazeera.

“It is a little bit ironic for the US to sort of trumpet citizens’ privacy concerns or worries about surveillance. It’s OK for them to collect the data, but they don’t want China to collect it.”

China, which itself has often been accused of spying on a mass scale, has said it would “firmly oppose” a forced sale of TikTok and that basing such an action on “foreign ownership, rather than its products and services” would damage investor confidence in the US.

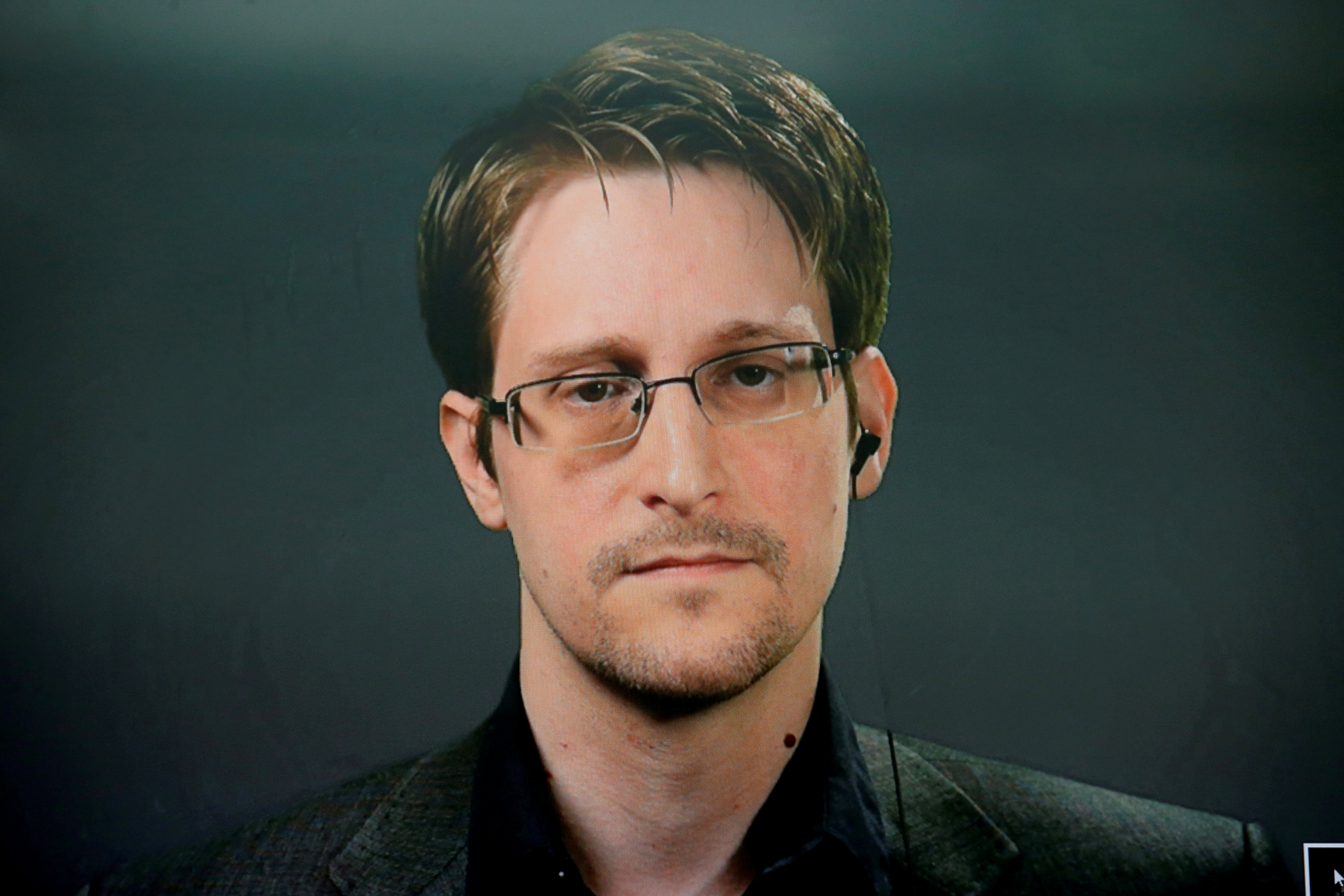

China has also in the past accused the US of hypocrisy on the issue of cybersecurity, pointing to spying programmes like PRISM, which was first revealed in 2013 by former NSA analyst and whistle-blower Edward Snowden.

There have been some indications that US officials see China, not TikTok itself, as the ultimate concern.

When cybersecurity officials in the US state of Connecticut last year reached out to the FBI for advice on whether to ban the app on government devices, an agent reported back that inquiries with HQ indicated that bans introduced in other states appeared to be based “on news reports and other open-source information about China in general, not specific to Tik Tok.”

“The big concern there that people seem to have is that the Chinese government can access data on [TikTok’s Chinese] servers like it has in the past, or that that data may be misused,” Cooper Quintin, a senior staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told Al Jazeera.

“All of that is true and all of that is bad, but all of that is also true of most of the other major social media apps and US-based social media companies.”

While Section 702 has been renewed twice since its original passage in 2008 with large votes, in 2012 and 2018, its prospects for reauthorisation this time around appear less certain amid waning support for the law – although criticism of its provisions has focused squarely on the rights of US citizens.

Some Republicans have signalled their opposition to renewing Section 702, unless this is done with significant changes, amid growing scepticism of US intel agencies among conservatives following the FBI’s illegal spying on Carter Page, a former campaign aide to former President Donald Trump.

Some Democrats, such as Oregon Senator Ron Wyden, have also long raised concerns about the sweeping nature of the law. Last week, Representative Pramila Jayapal, a Democrat from Washington, said the law should be reformed to “overhaul privacy protections for Americans”.

Meta, Apple and Google parent company Alphabet have also been lobbying for changes to Section 702 behind the scenes, Bloomberg News reported last week, including the requirement for a warrant for searches involving US citizens and the ability to publicly disclose how often they are asked to hand over data and what kind of information they must provide.

Although intended to target communications between foreigners, Section 702 in practice also captures the communications of US citizens who interact with foreigners.

The NSA and CIA are allowed to carry what critics describe as “backdoor” warrantless searches of US citizens’ communications that are collected incidentally if they believe it will yield information about foreign intelligence.

The FBI can also search through these communications, but is required to obtain a warrant for criminal investigations not related to national security.

US officials have repeatedly claimed that the law has been instrumental in safeguarding national security, citing its use in thwarting cyberattacks by adversaries such as China and Iran and the assassination of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri.

While US officials insist that their focus is on national security threats, civil liberties advocates say “foreign intelligence” could include effectively any communications, including those of journalists, human rights advocates and ordinary citizens, deemed of interest to the US government.

“The problem is that fundamentally the standard is extremely low, it’s a very broad authority,” said Ashley Gorski, a lawyer at the ACLU’s National Security Project, adding that “targets” do not have to be suspected of any crime.

“They don’t have to have any connection to terrorism. They can be journalists. They can be human rights workers abroad.”

Some critics argue that TikTok’s collection of data is little different from other platforms and that the push for a ban is a distraction from a far bigger problem which Washington has shown little appetite to address: a glaring lack of legal protections for personal data.

A US ban on TikTok would do nothing to stem the rampant sale of personal information and metadata that is collected by all social media companies, including those based in the US. US tech companies’ relatively lax privacy norms remain a sticking point in Europe, which has much stronger data protections.

“When somebody puts the TikTok app on their devices, it’s known to collect certain information about the user just as any other app made by a company based in the United States,” Mike German, a former FBI special agent and fellow at the Brennan Centre for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program, told Al Jazeera.

“To the extent that a hostile foreign power could get access to that information, I’m sure there’s some use they could make of that information,” German said. “But why wouldn’t they just buy it on the open market like the American government does?”

Vedran Sekara, an assistant professor at the IT University of Copenhagen, said the moves to restrict TikTok appeared to be “more political than good policy”.

“If politicians and lawmakers really were interested in protecting people from ‘evil’ or ‘nefarious’ tech companies, they should instead focus on regulating the entire tech and social media industries rather than just focusing on one company,” Sekara told Al Jazeera.

US social media platforms like Facebook, Google, and Instagram have themselves landed in hot water over their handling of their customers’ data, from hacking-related leaks to improper access by employees.

Some platforms have also faced scrutiny over their human rights records, much like TikTok, which has been known to censor content deemed sensitive to the Chinese government, including information related to LGBTQ issues.

Both Twitter and YouTube recently censored a BBC documentary that was critical of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the request of New Delhi. Facebook also faced blowback for allowing its platform to be used to promote violence and ethnic cleansing in Myanmar.

Also troubling to some observers is the precedent a US ban on TikTok would set for other countries.

“Essentially, the US is creating a template for other despotic authoritarian or even protectionist governments to use national security as a guide to prevent competition in the market and to lay claims over proprietary technologies,” Jyoti Panday, an India-based researcher at the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Internet Governance Project, told Al Jazeera.

Washington giving US tech companies a “free card” while restricting foreign companies would be “basically signalling to other countries or nations that sovereignty is the ultimate game in regulating cyberspace”, Panday said.