From working 20 to 30 hours of unpaid overtime each week in one of Australia’s fanciest restaurants to picking fruit while being exposed to dangerous chemicals for less than $10 an hour, the underpayment of migrant workers is rife.

The Grattan Institute’s new report, Short-changed: How to stop the exploitation of migrant workers in Australia, show a broad pattern.

We’ve used two nationally representative Australian Bureau of Statistics surveys of employees and employers – Characteristics of Employment and Employee Earnings and Hours – to find out whether employees are paid below the national minimum hourly wage in Australia, currently $21.38 an hour or $26.73 an hour for casuals.

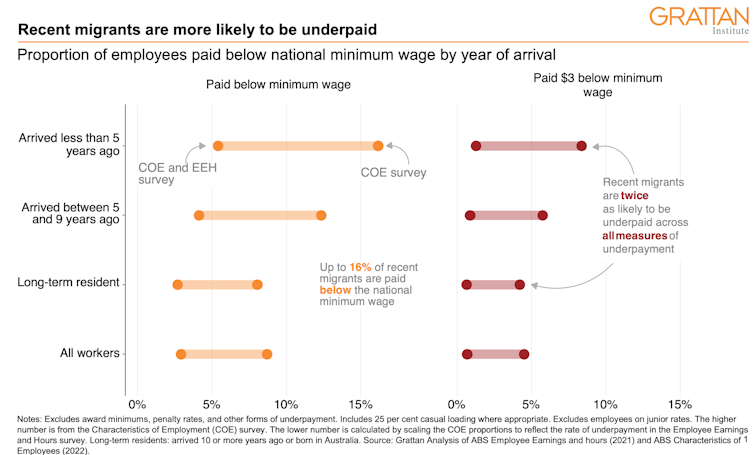

We estimate that recent migrants – those who arrived in Australia within the past five years – are twice as likely to be underpaid as migrants who have been in Australia for at least 10 years, and those born here.

Underpayment is widespread

In 2022, 5% to 16% of employed recent migrants were paid less than the national minimum wage. Between 1% and 8.5% of recent migrants were paid at least $3 less than the hourly minimum.

This compares with 3% to 9% of all employees in Australia being paid below the national minimum wage; with 0.5% to 4.5% paid at least $3 an hour less.

These numbers are likely to under-represent the extent of underpayment because our analysis only counts those being paid less than the national minimum wage.

It does not count cases where workers are underpaid against appropriate award rates, which typically pay more than the national minimum wage, penalty rates, or are not paid their superannuation.

Factors contributing to exploitation

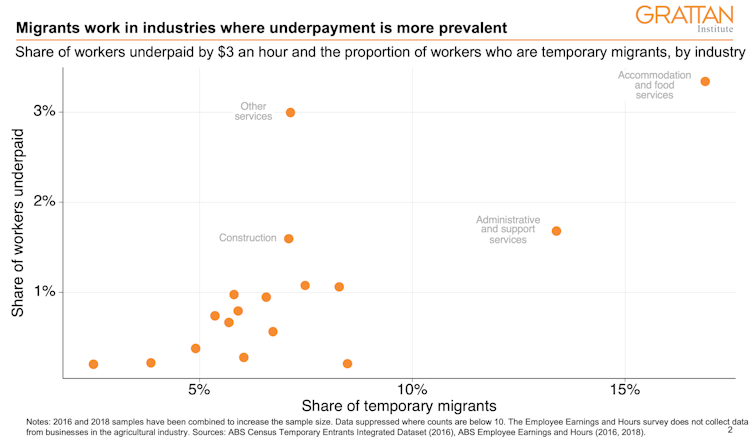

Part of reason recent migrants are more likely to be underpaid is because they tend to work in industries where underpayment is more prevalent, such as hospitality and agriculture.

For example, temporary visa holders account for nearly 20% of workers in hospitality, the industry with the highest reported rate of underpayment.

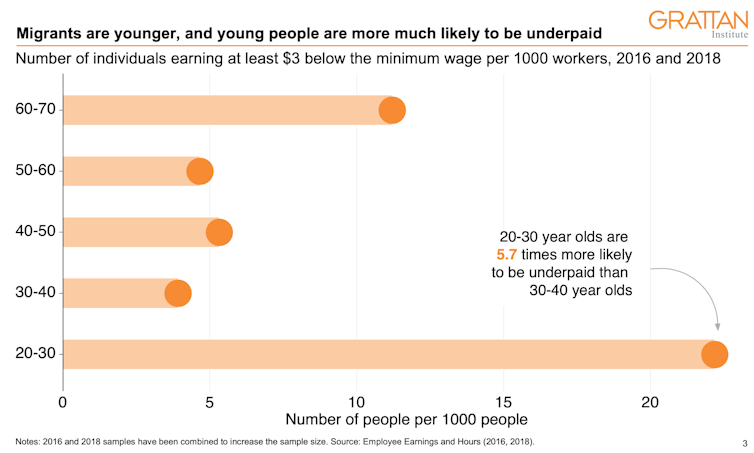

Migrants also tend to be younger workers. Employees aged 20 to 29 are nearly six times more likely to be paid less than the national minimum wage than workers aged 30 to 39.

But even after accounting for age, industry and other demographic characteristics, migrants are still more likely to be underpaid.

Migrants who arrived in the past five years are 40% more likely to be underpaid than long-term residents with similar skills working in the same job with the same characteristics. Migrants who arrived five to nine years ago are 20% more likely to be underpaid.

Several things explain this.

First are visa rules, which make temporary visa holders more vulnerable to exploitation. For example, many international students put up with mistreatment for fear their visa may be cancelled for working more hours than permitted by their visa rules. Two-thirds of recent migrants are on a temporary visa.

Migrants have less bargaining power than local workers, partly because they have small social networks to help them find a job. They may not know what workplace rights they are entitled to and face discrimination in the labour market.

Read more: What's in a name? How recruitment discriminates against 'foreign' applicants

Our analysis shows the likelihood of underpayment is also higher among those working less-skilled jobs with fewer qualifications.

Without change, underpayment will rise again

Rates of underpayment for migrant workers and locals alike have fallen since the pandemic began

In 2018, 8% to 22% of recent migrants were paid less than the minimum hourly wage (compared with 5% to 16% in 2022).

This probably reflects the decline in the number of temporary visa holders living in Australia, especially students and working holiday makers, and labour shortages boosting worker’s bargaining power.

But with borders open again and temporary visa holders coming back in big numbers, the rate of underpayment seems sure to rise again without action from government to stamp out exploitation.

The federal government needs to reform the visa rules that make migrants vulnerable, boost resources to enforce workplace and migration laws and make it easier for migrants to claim money owed.

Underpayment has been widespread for too long. Now is the time to put a stop to it.

Read more: How to improve the migration system for the good of temporary migrants – and Australia

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments, $4 million from BHP Billiton, and $1 million from NAB. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute's board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and contribute to funding Grattan Institute's activities. Grattan Institute also receives funding from corporates, foundations, and individuals to support its general activities, as disclosed on its website. We would also like to thank the Scanlon Foundation for its generous support of this project.

Trent Wiltshire and Tyler Reysenbach do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.