"It's the Ku Klux Klan!", say some tourists unfamiliar with Spanish Holy Week when they see the penitents accompanying processions in the streets.

The elder brother of the Archconfraternity of Jesús de Medinaceli in Madrid, Miguel Ángel Izquierdo, explains to Euronews that this is a common comment every year: "You have to explain to them that it has nothing to do with anything.

However, although the supremacist movement adopted a costume similar to that of the Nazarenes, the capirote, a conical form of a Christian pointed hat, predates even the founding of the United States. In Spain, the first pointed hats, which are the origin of today's capuchons, appeared in the 16th century with the Inquisition.

Shame and humiliation

When the Catholic Monarchs established the Holy Tribunal, an era of Catholic orthodoxy began in Castile, punishing crimes ranging from blasphemy to heresy. "During the autos de fe, the Inquisition imposed on heretics and condemned them to wear the 'sambenito', a special habit, similar to a poncho, which was a form of humiliation, a visual punishment and a public scorn. In some cases, especially with serious convictions, it was topped with a pointed capirote," historian David Botello tells Euronews.

The origin of the capirote

"The origin of the capirote can be traced back to two sources: medieval spirituality and the Inquisition, because penitents covered themselves out of humility, so that they would not be recognised", adds Botello, author of "Don't touch my Bourbons" (No me toques los Borbones), among many other books in which he delves into the history of Spain.

Some were condemned to death and presented themselves in these clothes for execution, which could be death by drowning if they repented of their sins, or they could be burned alive in a public square. Since they were people who were serving a capital sentence, they were called penitents.

Paintings such as 'Auto de fe de la Inquisición' by Francisco de Goya, painted between 1812 and 1819, illustrate such clothing. The question is how the different confraternities adopted the same symbolism in their processions. "The confraternities took this attire and redefined it: what was a humiliation, they turned into a voluntary penance," says Botello.

"The capirote became a symbol of spiritual elevation: the higher the capirote, the closer you got to God," explains the historian. Originally, in the processions, the Nazarenes were dressed more simply, but "over the centuries, the confraternities improved the design: the hood went from being a simple hood to having a structure and colours or insignia were incorporated". Despite all these changes Botello stresses that "the essence of the dress remains the same: anonymity, recollection and penitence".

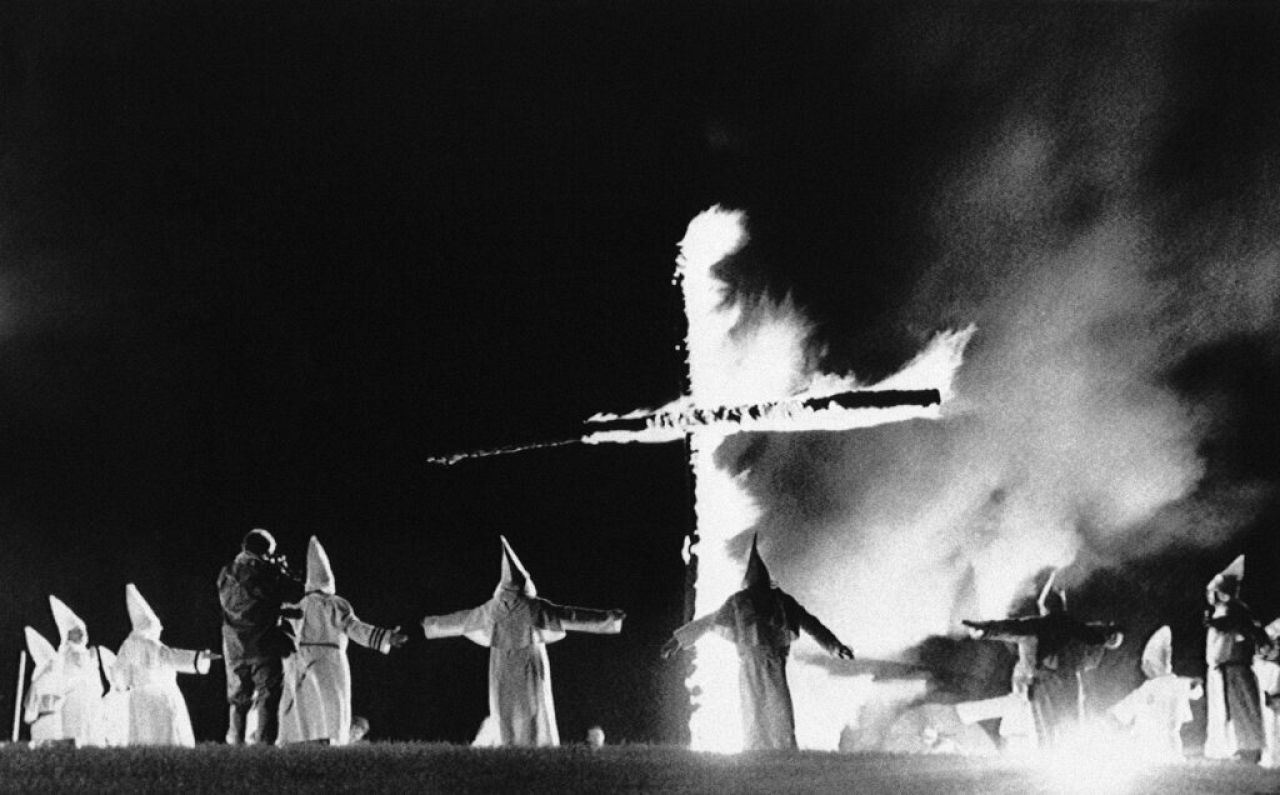

Why did the Ku Klux Klan adopt the penitents costume?

Whatever its origin and evolution, the similarity of the uniforms chosen by the Ku Klux Klan at the end of the 19th century is evident. There are several theories on the matter, "some point to an indirect visual inspiration, maybe a KKK designer saw an illustration, a lithograph or a scene from Holy Week in Spain and thought: 'this imposes'," says Botello.

That possibility coincides with a clipping from 'Opportunity' magazine, published in New York in 1927, which said: "One need only glance at it to see the similarity to the white robes and hoods worn by the Ku Klux Klan in our country. To all appearances, the American organisation copied the dress of those Christian believers," the text says.

However, Botello insists that there is no conclusive proof of the origin of the supremacists' clothing. "It could also be pure coincidence: many cultures have used hoods to hide their identity, from medieval executioners to members of some sects," he says.

Whether or not it is cultural appropriation is another debate. What David Botello is clear about, however, is that it is "an aesthetic deformation with radically opposite ends, as Holy Week is a living manifestation of faith, history and tradition that has been reinvented over the centuries".

"To confuse a penitent with a supremacist is a disastrous mistake, which erases centuries of spirituality and collective memory", says the historian, who firmly believes that "the hood can be imposing and scary, but ignorance is much scarier".