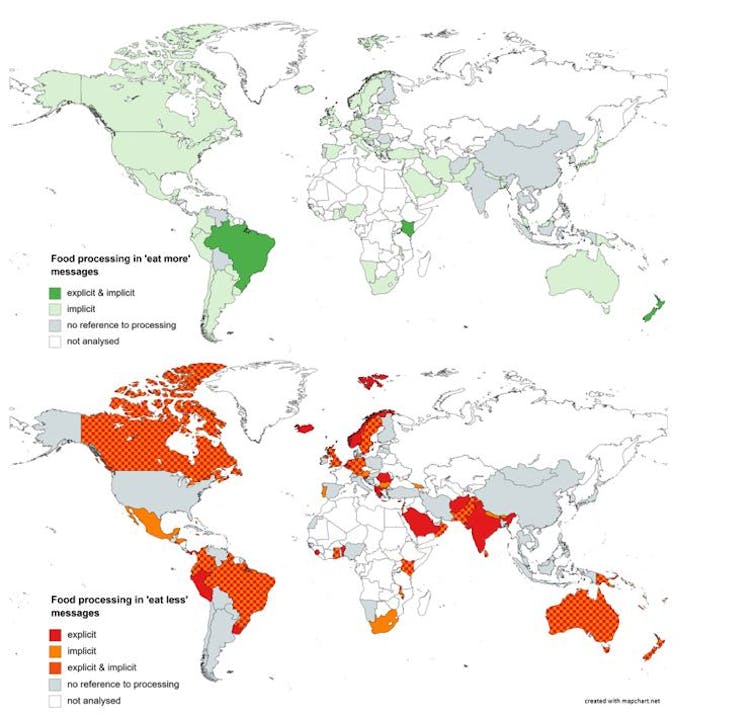

Straightforward guidance about ultra-processed foods is rare in national dietary guidelines. Only seven countries refer to “ultra-processed foods” explicitly. They are Belgium, Brazil, Ecuador, Israel, Maldives, Peru and Uruguay.

The term “ultra-processed food” is clearly defined in the NOVA framework as “formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, that result from a series of industrial processes”. The framework puts foods into four categories according to their degree of processing. Ultra-processed food products include many soft drinks, biscuits, processed meats, instant noodles, frozen meals, flavoured yoghurts and bread products. Consumption of ultra-processed food has been linked to health and environmental harms.

To better understand how national dietary guidelines communicate advice about ultra-processing, we conducted an analysis of 106 guidelines around the world to explore if – and how – they talked about ultra-processed foods. Dietary guidelines are a key component of nutrition policies and are important in transforming nutrition research into policy actions. An example would be informing school meal standards.

We found dietary guidelines used a range of euphemisms to refer to the presence or absence of processing. These ranged from canned, to frozen, packaged, ready food and instant.

Many guidelines also used the term “processed”. But this captures a vast range of technologies, ranging from basic cooking (such as chopping and boiling), to beneficial processing (such as fermenting for preservation), through to sophisticated forms of industrial processing (such as hydrogenation, a chemical process often used to modify fats, and extrusion, a physical process to shape foods). These do not have the same health or environmental impacts, and conflating them in dietary advice is unproductive.

The absence of clear and actionable guidance is a risk for public health and the environment. Strong guidance around the harms of ultra-processing can help catalyse the development of other food and nutrition policies, such as taxes or restrictions on marketing to children. Collectively, these policies can foster healthier and more sustainable food environments.

Figuring out healthy from unhealthy

When trying to evaluate how healthy or sustainable a processed food is, two key considerations are the nature and purpose of processing. Freezing and canning are often used to preserve foods, and this can be beneficial from a food safety and food security perspective. But the use of artificial colours or thickeners can be used to imitate the taste and texture of whole foods, or to mask unpleasant attributes caused by processing.

Dietary guidelines can do a better job communicating these nuances to clarify the differences between beneficial and harmful forms of processing.

While seven countries used the term processed or ultra-processed, most referred to food processing euphemistically. Examples include, from South Africa, the phrase:

eat more…unrefined ready-to-eat cereals, oats, mealie meal, maltabela, muesli

or from Nepal:

eat more wholegrain cereal products and less refined cereals.

We found that advice to reduce consumption of “processed”, “highly processed” or “ultra-processed” foods was more common in low- and middle-income countries. In high-income countries, this was often limited to advice about processed meat.

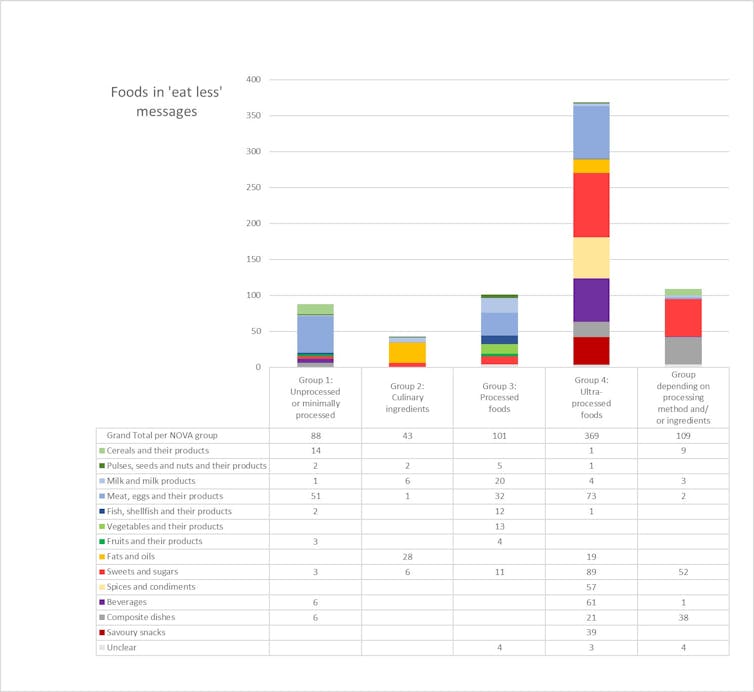

Most guidelines followed the advice of the Food and Agricultural Organisation and offered food-based advice. More than half of the examples of discouraged foods were ultra-processed. But some examples were minimally processed foods or minimally processed ingredients. Examples include meat, butter.

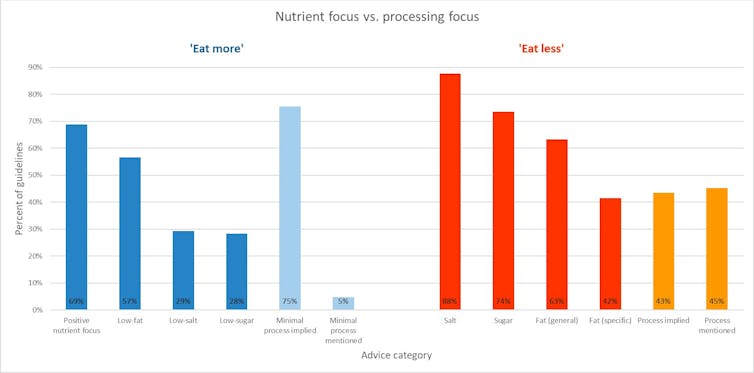

These food examples highlight contradictions between processing-focused and nutrient-focused advice. Meat, butter and natural yoghurt, for example, are high in fats, but minimally processed. Whereas diet soft drinks or low-fat flavoured yoghurt are low in “harmful nutrients” but ultra-processed.

We found that the term “processing” was more common than we expected. Nevertheless, we found that dietary guidelines often provoked confusion about ultra-processed foods, discouraging consumption of some minimally processed foods and potentially even encouraging consumption of ultra-processed ones.

Clear advice about processing was rare. Yet all but one of the 106 guidelines we analysed provided nutrient-focused advice. Take this example from South Africa:

Use salt and food high in salt sparingly.

These contradictions in dietary advice risk confusing citizens.

Changing the ultra-processed food system

To avoid consumer confusion, and to facilitate the uptake of evidence about ultra-processed food policies such as school meal guidelines and front-of-pack labelling, we recommend three actions.

First, dietary guidelines can provide examples of less obvious ultra-processed foods. While soft drinks and fast foods are common examples, others include processed breads, flavoured yoghurts, sauces, breakfast cereals and ready meals.

Second, dietary guidelines can provide more explanation about how to identify ultra-processed foods based on the nature and purpose of processing. Beyond a focus on the composition of foods (in other words, their ingredients), ultra-processed foods are often heavily marketed with health claims or colourful cartoon packaging appealing to children.

Powerful food companies, which are often headquartered in high-income countries, are driving the global expansion of ultra-processed foods into industrialising countries such as South Africa and China. Greater scrutiny of the practices used to promote them is an important step towards reducing their consumption.

Finally, policy makers can use dietary guidelines to inform the development of other food policies to support citizens to reduce consumption of ultra-processed foods. This could include restrictions on advertising (especially to children), taxes or front-of-pack labels that discourage consumption.

It is also important to enable consumption of minimally processed foods, such as through subsidies or other initiatives, to make them more affordable and accessible. This could include support for living wages paid to workers in the food system, such as Australia’s recent initiative to pay farm workers the minimum wage.

These initiatives are essential to ensure that everyone has an equitable opportunity to access healthy and sustainable foods.

Daniela Koios, an author on the academic paper, contributed to this article.

Jennifer Lacy-Nichols has received funding from The George Institute of Global Health. She is a member of the People's Health Movement and the Healthy Food Systems Australia advocacy group. The findings of the research reported in this article, and the views expressed, are hers alone and not necessarily those of the above organisations.

Priscila Machado receives funding from an Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellowship provided by Deakin University, and has received funding from the Australian Research Council and Sao Paulo Research Foundation. She is a member of the Nutrition Society of Australia, the World Public Health Nutrition Association and the Healthy Food Systems Australia advocacy group. The findings of the research reported in this article, and the views expressed, are hers alone and not necessarily those of the above organisations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.