Now is not the right time for the BBC to cancel Top Gear. I don’t know exactly when that was. In 2019, when a presenting reshuffle saw Friends star Matt LeBlanc leave the show? Maybe. In 2015, when Jeremy Clarkson assaulted a producer, resulting in the departure of the Clarkson-James May-Richard Hammond hosting triumvirate that had fronted the show since its 2002 revival? Probably. But no – it should have been earlier still. When Clarkson, in 2014, was filmed muttering “n*****” while reciting a racist nursery rhyme in a Top Gear outtake? Or earlier that same year, when he used the term “slope” on camera in an oblique reference to an Asian person? Or one of the other countless offensive moments from the show’s chequered past? There’s no “three strikes and you’re out” here. Top Gear has had more strikes than a pro bowler.

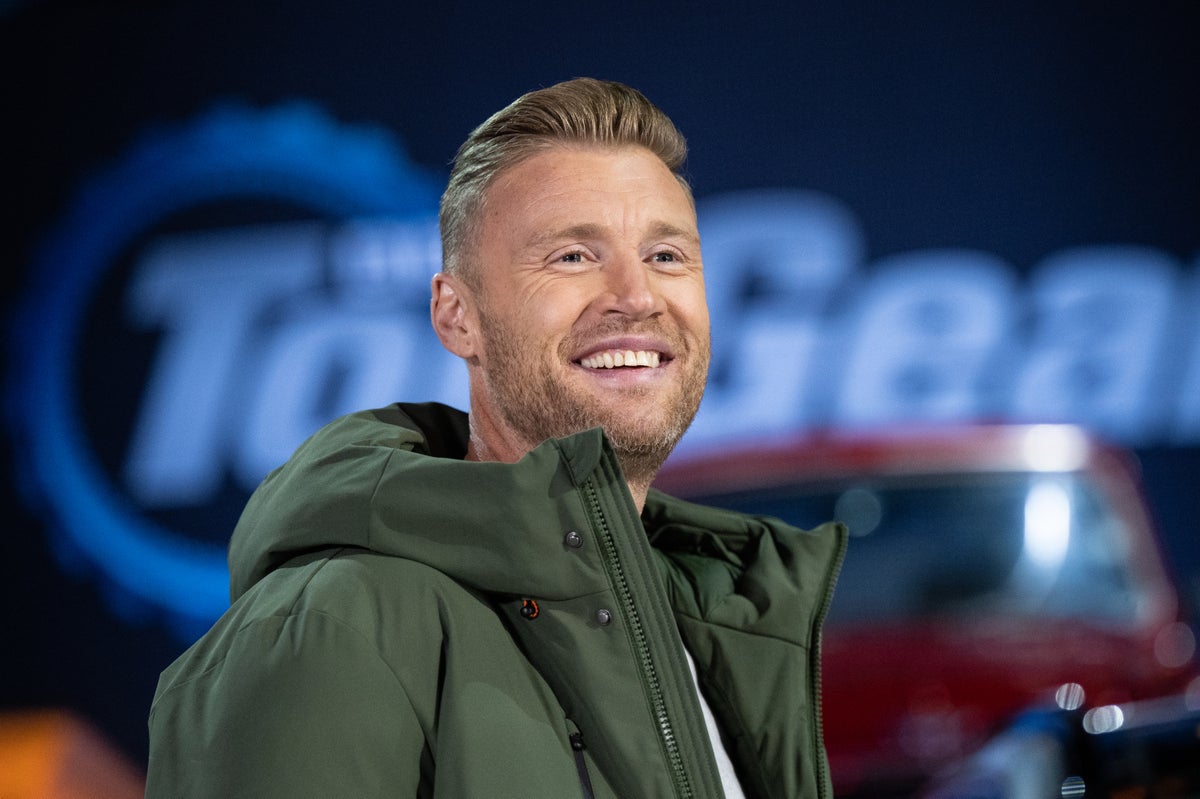

And yet, none of these are the reason that Top Gear’s survival has now been thrown into doubt. Instead, the show has been rocked by concerns over health and safety, following the near-fatal car accident involving presenter Freddie Flintoff last October. The ex-cricketer, who joined the show in 2019, was pictured this week for the first time in public following the accident – his injuries, nine months on, still brutally visible. Flintoff’s accident wasn’t the first to have occurred in the making of Top Gear. It’s not even the first to involve Flintoff, who is said to have narrowly escaped serious harm in a vehicular accident in 2019. Hammond was left in a coma in 2006 after a grievous crash; Clarkson and current host Paddy McGuinness have also both been in accidents.

The show’s safety protocols shouldn’t be fodder for uninformed speculation: the BBC commissioned an investigation to assess the facts of the case. But, for a series so simperingly enamoured with the joy of automobiles, Top Gear presents a pretty compelling case for the perils of driving. The broadcaster has yet to make a decision on when – and, seemingly, if – Top Gear will resume filming, but there must surely first be a reckoning over the risks and the ethics of persevering after multiple accidents.

The truth is, Flintoff’s accident may have provided the perfect pretext to cut loose a programme that has long passed the point of redundancy in our televisual lineup. Including its original run (1977 to 2001), some variation of Top Gear has been on the channel for nearly half a century. Even if you leave aside the transgressions of Clarkson and co, the series has been struggling to justify its own existence for a while. The rotation in presenters since 2015 – LeBlanc, Chris Evans, Sabine Schmitz, Eddie Jordan, and Rory Reid have all joined and left the show within the past seven years, with Flintoff, McGuiness and Chris Harris being the current frontmen – testifies less to the series’ creative effervescence than a failure of any host to make a real mark. The banter is insipid, the format tired.

Former presenter Richard Hammond was left in a coma for two weeks after a crash in 2006 while filming for the show— (BBC)

It could be said, too, that the very premise of the series is antiquated in our modern era, when the devastating climate crisis has made cars seem less like a swishy convenience and more like an insidious factor in our own collective demise. True, McGuiness et al have never shared Clarkson’s obnoxious contempt for the environmental lobby, but there is still no shortage of love for our four-wheeled friends. I understand Top Gear can’t suddenly start recommending that everyone park their Toyota and take a nice stroll to work instead… but shouldn’t it? It speaks to a cavalierness about pollution and climate change that is outdated in 2023. It’s hard to imagine most modern teenagers watching an episode of Top Gear and thinking anything other than, “Who are these car-adulating freaks?”

Of course, I realise that there are still plenty of motoring fanatics out there who rely on Top Gear for their sweet petrol-y buzz. They can’t all have followed Clarkson to Amazon’s Grand Tour. After a severe years-long dip starting in 2016 – when the viewership more or less halved – Top Gear has recovered to a place of good health in terms of audience figures. (The 33rd series premiere drew 4.86 million.) There’s no reason to stop now on account of its metrics. Popularity, however, has rarely been Top Gear’s problem.

If Top Gear were to call it quits now, it’d be an unceremonious end for what is, objectively speaking, a British TV institution. But what’s the alternative? The best case scenario, at this point, would be that it coasts along for another five or 10 years, avoiding both vehicular disaster and racist controversy. Is that really worth the human risk? Now might not be the right time to cancel Top Gear. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t do it anyway.