In 2012, HSBC was fined $1.9bn and entered into a Deferred Prosecution Agreement for facilitating the laundering of money by the Mexican drugs cartel headed by Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. The US Justice Department had been all set to bring criminal charges against HSBC executives and seek jail terms but was persuaded to strike a deal instead.

One of those who had been at the Justice Department and had paid close attention to what was unfolding was Richard Elias.

“Rich” Elias went to Missouri Law and won a clutch of honours. He started out defending companies, but, “after seeing first-hand how corporations often use their money, power, and influence to intimidate and thwart smaller plaintiffs”, he switched to pursuing corporate misconduct.

Said Elias: “I was in the Department of Justice when the HSBC DPA was entered. It was a very unpopular agreement within the department. I was not working on it but I was aware of it. I was outraged by HSBC’s conduct and how that was symptomatic of larger problems with the banks. It had always stuck with me.”

Elias moved into private practice, “with the mission to bring cases of important public interest.” HSBC fitted the bill.

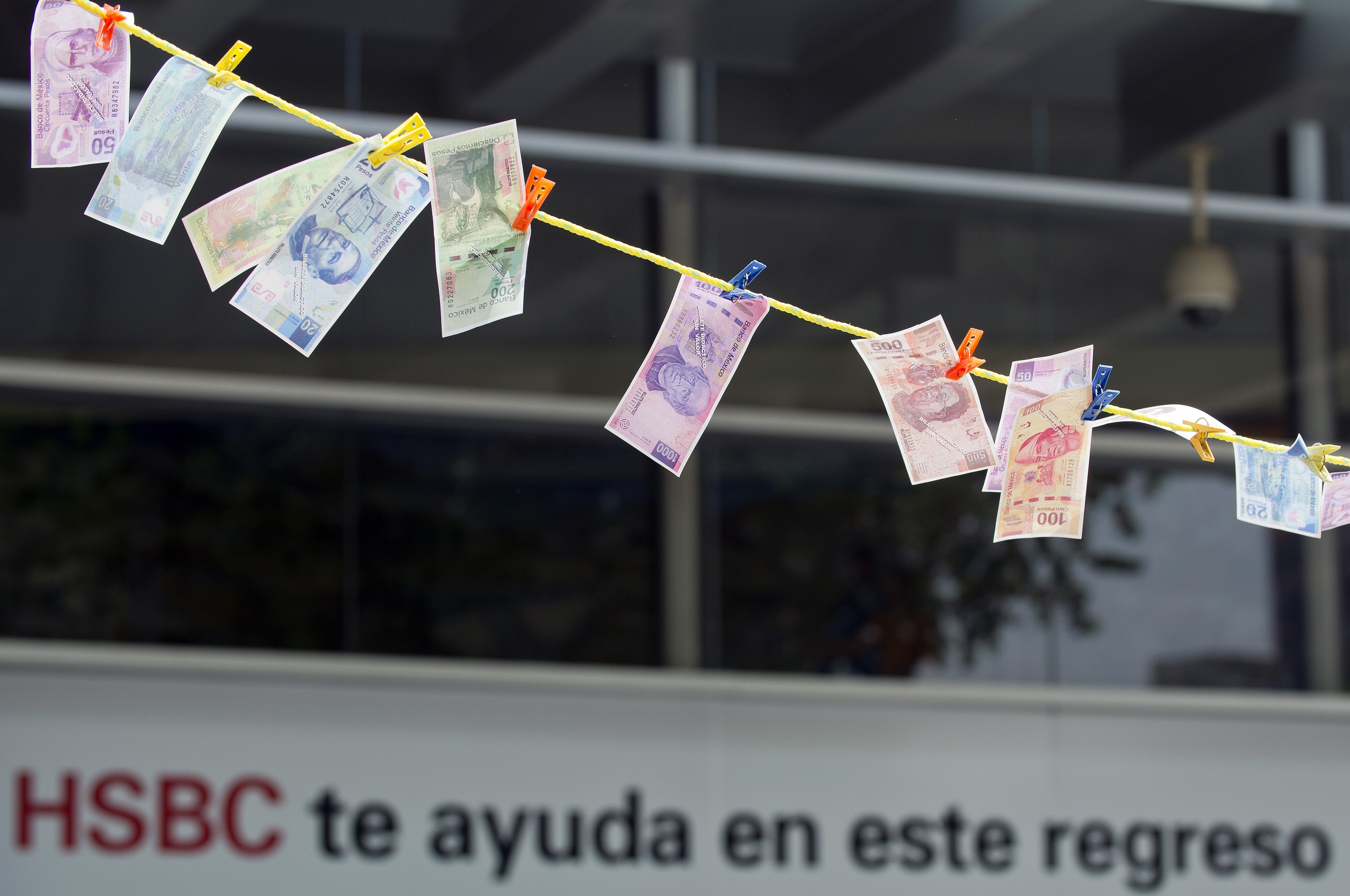

What he saw, he said, was the committing of “very gruesome acts of violence” by the drug traffickers, and HSBC, the bank that had laundered their money, receiving only “a relatively light penalty – that’s what made it so unpopular in the Department of Justice.” Said Elias: “It was beyond dispute that HSBC constantly allowed billions of dollars to be laundered through its branches. It was egregious what they’d done – accepting large amounts of US dollars in cash, $200,000 a time, receiving specially packaged boxes filled with cash that were the same size as the cashiers’ windows. It was unmistakable what was happening.”

The US Anti-Terrorism Act, “imposes liability on those who commit a terrorist act and those who provide support knowingly or recklessly to those who commit the terrorist act.” The more Elias looked at it, the more it was his belief that, “by laundering their money, HSBC materially supported the cartel and gruesome acts of terror.” Where a bank and a drugs cartel were concerned it was though, largely untested law. Nevertheless, Elias decided to give it a go. He would sue HSBC under the Anti-Terrorism Act.

Elias and his colleagues went back to the records. They were looking for US victims of Sinaloa violence (they had to be US citizens for the statute to apply).

They were murdered by wrapping their heads round and round in duct tape. Their cause of death was asphyxiation. The bodies were found discarded in the back of a truck

One Elias alighted on was Rafael Morales, Jr In 2010, Morales Jr and his family were celebrating his wedding ceremony at El Señor de la Misericordia Catholic Church in Ciudad Juárez, the city where his new bride had been raised. As the congregation exited the church, assassins from the Sinaloa, all bearing assault rifles, were waiting for them in the church courtyard. In the distance, barricading the road to the church, were Mexican federal police officers who were corrupt and working for the cartel.

Chapo’s assassins were there under orders to kidnap Guadalupe Morales. People at the wedding tried to dissuade the orchestrator of the attack, Irvin Enriquez, saying they were innocent people. Enriquez ignored their pleas.

They ordered everyone, including small children, to lie face down in the dirt. In a panic, one man attempted to flee but was shot in the back and killed. They began beating Guadalupe in front of the congregation. Rafael Jr’s brother and best man, Jaime, screamed for the men to stop, at which point they grabbed him, his brother, and his uncle, forced them into two separate vehicles, and left. The corrupt Mexican police then closed the courtyard gate and locked it, trapping the horrified wedding guests inside. The Morales men were then transported to two separate “safe houses” where they were tortured.

Later that evening, Enriquez was in a meeting in Sunland Park, New Mexico when he received a radio call from one of the Sinaloa cartel killers by two-way radio. Enriquez was excited and bragging about the wedding abductions. The assassin had the three Morales men identify themselves over the radio. People in the meeting again encouraged Enriquez to release the men, stating that they were innocent. Enriquez nevertheless ordered them to be killed.

They were murdered by wrapping their heads round and round in duct tape. Their cause of death was asphyxiation. The bodies were found discarded in the back of a truck in a residential neighbourhood in Juárez – they’d been tortured and tied, and their heads were still bound in the tape.

Various Sinaloa members were indicted for the murder of Morales Jr in the US District Court for the Western District of Texas, including Enriquez, José Antonio Torres Marrufo, a senior enforcer for the cartel, and Chapo himself.

Enriquez and an associate subsequently pleaded guilty to conspiring in the US – in Texas and New Mexico – to murdering Morales Jr, Jaime Morales and Guadalupe Morales in a foreign country.

At the time of his death, Morales Jr was a US citizen who lived in La Mesa, New Mexico with his parents, sister, and nephews. Elias persuaded his parents, who loved their son very much, to join an action.

The Morales family was just one grieving set. In all, Elias had five lots of plaintiffs for five murdered US citizens. “We sat down with them and talked to them – it wasn’t easy because they’d been through so much,” he said.

“We were proposing holding HSBC accountable in a way it had not been held accountable before. It was easy for the unengaged to say that was a hefty fine. But they’d still reported $17bn worth of profits and $22bn the year before. The fines were not deterring conduct. There were ways for us to play our part – the Anti-Terrorism Act opened the doors of the US courts to victims of international terrorism and those providing material support to terrorists. It also contained a punitive element of triple damages.” After 9/11, the 1996 Anti-Terrorist Act was amended to allow victims to receive compensation from organisations that provide material support to groups that commit terror acts.

Added Elias: “The evidence is very compelling that there were individuals in the bank who were more than just negligent. There were members of the bank who knew full well the amounts of illicit dollars that were being laundered and, in several instances, there were employees of the bank who were complicit and were working on the money-laundering schemes, none of whom have been held accountable.”

Following the fine and DPA, he said, “The only tool we have left is damages for the victims. I would like to see criminal prosecutions; individuals need to be held accountable – there is a culture within the Justice Department of not holding individuals accountable in financial institutions who commit significant crimes.”

What the complaint does allege, however, is that money laundering is the lifeblood of the cartels, through which they pay for their extensive infrastructure

He said: “If you sell a gram of cocaine on the street you’re going to jail. If you’re complicit in laundering billions of dollars, your organisation pays a fine, and you, the executive who oversaw, and was potentially complicit, you’re not individually investigated and you don’t even have to give back the bonuses you received during the years it was going on.”

In 2016, Elias brought the civil claim in the Southern Texas Federal District Court in Brownsville, close to the border. “It’s a border town and they have a better understanding there of what the cartels are, rather in a more removed place like New York.”

Although other violent drug-trafficking organisations, such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), have been designated terrorists by the State Department, a drugs cartel so far had not been. “It was unprecedented,” said Elias. “But the definition is ‘anyone who commits acts that are dangerous to human life that are intended to coerce, intimidate the civilian population and the government.’”

The suit, Zapata v HSBC Holdings Inc, maintained that as a result of the bank’s “material support” for the drug traffickers, “numerous lives, including those of the plaintiffs, have been destroyed … Without the ability to place, layer and integrate their illicit proceeds into the global financial markets, the cartel’s ability to corrupt law enforcement officials, and acquire personnel, weapons and ammunition, vehicles, planes, communications devices, raw materials for drug production and all other instrumentalities essential to their operations would be substantially impeded. Thus, by facilitating the laundering of billions of dollars of drug cartel proceeds through its banks, HSBC materially supported … terrorist acts.”

HSBC vowed to fight the action every inch of the way. Elias lost first-time round in New York and in 2020, went to appeal.

At the Second Circuit Appeal Court in the Courthouse, in Foley Square in Lower Manhattan, Elias and his colleagues argued the lower court was wrong to dismiss the case because they had failed to show “terroristic intent” and “proximate causation”. They claimed that the fact HSBC provided “billions of dollars of money-laundering services “created a plausible inference” the bank acted with intent. The money laundering helped the Sinaloa carry out their terrorist activities and that showed sufficient support for what they were doing, enough for proximate cause.

They maintained that Congress intended the Anti-Terrorism Act to catch not just the actual killers and perpetrators of violence but those in the “casual chain of terrorism” so as to “interrupt or at least, imperil the flow of money”. Collecting damages against a terrorist organisation was recognised as “well-nigh impossible” but, they said, successful suits “against financiers of terrorism can cut the terrorists’ lifeline.”

Much could be made, they said, of HSBC “not intending” to help the drug traffickers or terrorists but the “plaintiffs do not allege that HSBC discreetly provided routine banking services. Rather, that [the Sinaloa] routinely walked into the local community HSBC branches with bundles of their blood money (sometimes in the millions of dollars) and HSBC openly accepted their deposits without question. In numerous instances, HSBC managers conspired with narco-terrorists to launder money.”

It wasn’t just that the bank supplied money-laundering services but that they knew that the Sinaloa were committing atrocities. The plaintiffs’ lawyers quoted a HSBC senior compliance official warning about what was going on and saying he did not want his sources fired or killed and him making the comparison with Afghanistan and Iraq. Said Elias: “It was not merely foreseeable that a substantial portion of the laundered proceeds would be used to execute their acts of terrorism – it was certain.”

They made it plain they did not allege they could trace the laundered money to each brutal murder. “What the complaint does allege, however, is that money laundering is the lifeblood of the cartels, through which they pay for their extensive infrastructure – including equipment, vehicles, personnel, and weaponry – corrupt public officials, and amass sufficient wealth and power to transcend from mere criminal organisations to the paramilitary forces they have become.”

They cited the US President’s Commission on Organized Crime and its report, The Cash Connection: Organized Crime, Financial Institutions and Money Laundering. The “existence of modern, sophisticated, often international services of financial institutions has contributed to the frightening financial successes of organized crime in recent years, particularly in the narcotics trade.” Said the report, without “the means to launder money, thereby making cash generated by a criminal enterprise appear from a legitimate source, organized crime could not flourish as it does now.”

HSBC’s lawyers struck back. They’d failed to show that HSBC had itself committed an act of “international terrorism” that caused the plaintiffs’ injuries. They’d alleged only that the defendants provided “arm’s length commercial banking services” to the drug traffickers. “Those acts are neither violent nor dangerous to human life, as the District Court held. And they do not objectively manifest the intent by the defendants to achieve a terroristic end.”

The plaintiffs alleged that on the one hand, HSBC facilitated the laundering of billions of dollars of drug trafficking proceeds. And on the other, they contend that the Sinaloa carried out the violence. Missing, said the HSBC team, was any direct connection between the two, between HSBC and the actual acts of murder.

On 16 October 2020, the appeal court ruled on Zapata v HSBC Holdings Inc. Elias and the Morales family and the other plaintiff families were slapped down. They agreed with HSBC. Yet again, HSBC was in the clear.

Extracted from Too Big to Jail – Inside HSBC, the Mexican drug cartels and the greatest banking scandal of the century, published by Macmillan out now