In a recent column about Oasis' Wonderwall, I pointed out that “really huge hits tend to be conventional in their broad strokes but weird and a little annoying in their details.” I started thinking a little deeper about this phenomenon, and decided that it warranted further investigation.

So here is my proposition: There are pop hits, and then there are songs that transcend genres and eras and persist for generations. I’m talking about the songs you hear at bar mitzvahs, in roller rinks, coming out of random car windows. These are the songs that my kids know, that my students know, that my aunts and uncles know, songs that you never need to seek out because they’re just there, like features of the landscape.

I believe that these songs have one thing in common: to really stand the test of time, a song has to be at least a little weird, and its weirdness has to be at least a little annoying. I will demonstrate this idea using songs from three different eras: the 1960s, the 1980s, and the early 2000s.

Before you skim the headers and start composing an angry email, I want to be clear that I love all five of these songs, very deeply. I have sung them, played them on guitar, transcribed them and studied them. These songs deserve to be popular, because they are appealing, original, and well-crafted. They bring people together by inspiring us to sing along and to dance. But they are also all eccentric.

You might see these eccentricities as regrettable flaws, or as charming idiosyncrasies. They are aspects of the songs that bother me. They don’t so much get stuck in my head as stuck in my teeth. There’s something perversely satisfying about metaphorically poking them with my tongue over and over and not being able to dislodge them. I find it inspiring that such immense crowd-pleasers are also so peculiar.

1. The Beatles - Hey Jude

I could do this whole list just about Beatles songs, because all of them are peculiar in some way, overtly or subtly. But Hey Jude stands out for the contrast between its overall welcoming accessibility and its few glaring flaws.

The first flaw is the line “the movement you need is on your shoulder”. It was meant to be a placeholder, a duplicate of “don’t carry the world upon your shoulder” from earlier in the song. Paul McCartney intended to replace it, but then he couldn’t think of anything else, so he just left it in. As I kid, I adored this song, and I drove myself nuts trying to figure out what that line meant. There was no internet back then, so there was no way for me to find out that it doesn’t mean anything at all.

The second flaw is the climactic “better, better, better, better, better, better, better, yeahhh!” at the end of the last verse. This sounds great and is exciting to listen to, but it ruins the song as a singalong, because no normal person can possibly hit that note. I sang it to my kids as a lullaby for several years, and always had to awkwardly fudge this line.

The final flaw is Paul’s fake Little Richard screams over the “na na na” part. I know some Beatles fans find them endearing. In his Number Ones entry about the song, Tom Breihan calls them stiff, forced and wince-inducing. I agree with Breihan, but it’s a testament to how powerful the “na na na” chant is that its uplifting vibe is impervious to Paul’s goofing around.

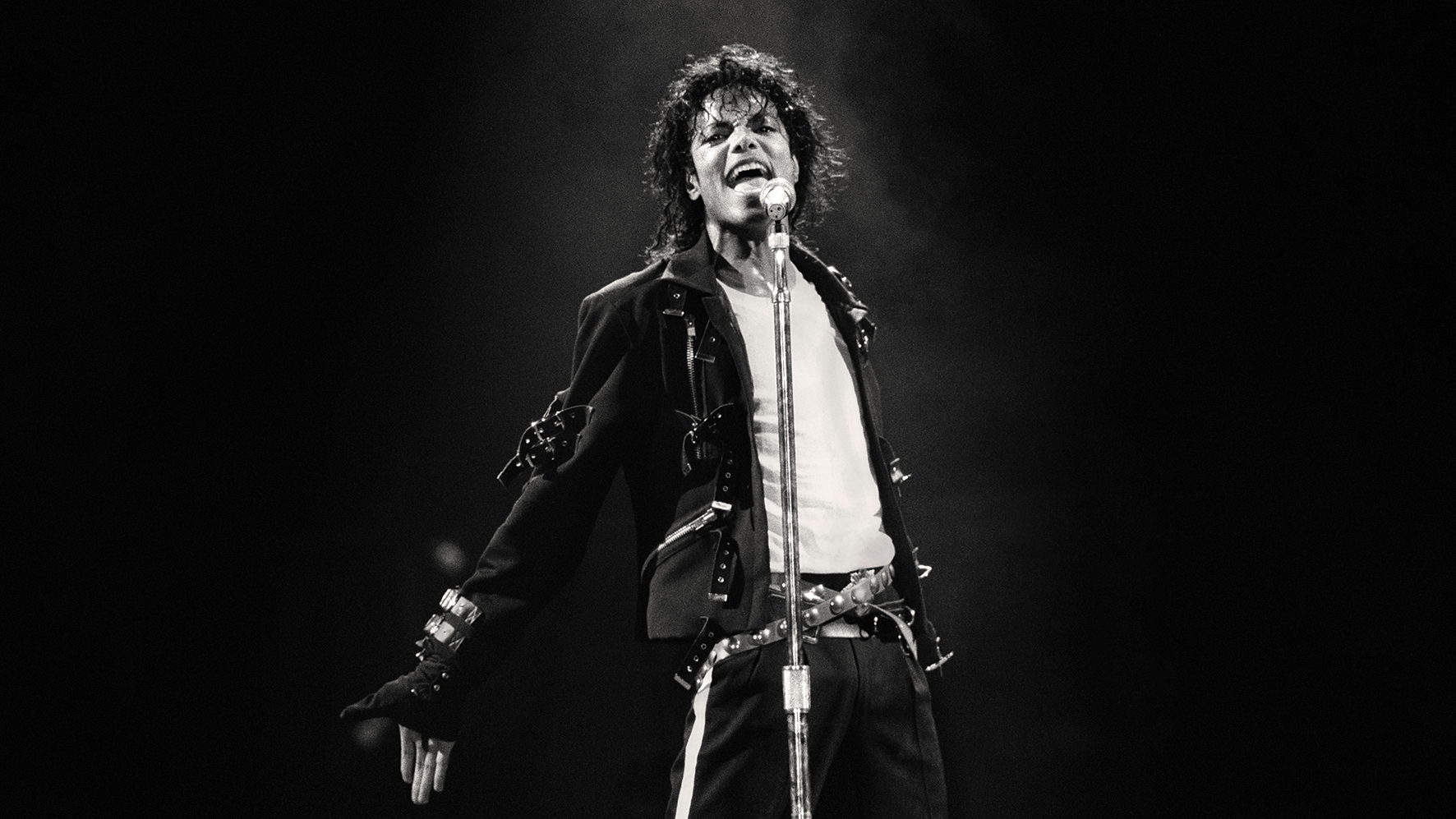

2. Michael Jackson - Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'

This song didn’t do the kind of numbers as a single that Beat It or Billie Jean did, but it’s the song that DJs play at the peak of the night, the one that gets everyone out on the floor. Michael Jackson always has a barely-contained anger seething under his most joyful grooves, and in Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ it’s right on the surface. The song is an eccentric one from its very first moments. The beat and bassline avoid the downbeat, which violates the most basic convention of Anglo-American popular music. The missing downbeat gives the entire groove an off-kilter, falling forward feeling. I love the effect, but it is definitely unsettling.

Because Michael doesn’t enunciate the lyrics very clearly, most people don’t even really know what they are. If you look them up, you may find them as baffling as I did at first: “You really can't make him hate her, so your tongue became a razor.” Okay. “You're a vegetable, you're a vegetable.” Sure. “Still, they hate you, you're a vegetable, you're just a buffet, you're a vegetable.” Right. I now know that Michael wrote the song to be sung by his sister Latoya, and that it was directed at their brothers’ gold-digging girlfriends. With that context, the lyrics make much more sense, but back in the 80s, who had that context? I certainly didn’t.

Even if you know the song’s back story, the chant at the end is still mysterious. We all assumed that it meant something in some African language, but again, in the dark pre-internet days, there was no good way to find out. The chant was adapted from Soul Makossa by Manu Dibango, but it turns out not to mean anything in its original context either. Makossa is a Cameroonian dance style, and Manu Dibango begins his song by playfully scatting around the word. It’s the equivalent of singing “boogie-oogie-oogie.” The chant’s opacity chant isn’t a flaw, necessarily, but it is a challenge for lovers of the song that its most memorable and uplifting part is a nonsensical imitation of a nonsensical phrase.

3. Hey Ya! - Outkast

This song is the weirdest one on my list, by a wide margin. The oddness begins with André 3000’s count-in: “One, two, three, uh!” The first beat of the song hits on the “uh”. That is not where it is supposed to be; the “uh” is beat four, not beat one. As in Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’, we are off-center from the very first downbeat.

The second oddity is Andre’s singing. He is one of the best hip-hop MCs of all time, with an effortlessly virtuosic flow to match his effortlessly brilliant lyrics. As a singer, however, he is… well, I don’t know how to describe him. He isn’t conventionally “good”, but he is strangely compelling to listen to. Is this song so much fun in spite of the taunting nasal tone or because of it? I genuinely do not know.

In Hey Ya!, the phrases are five and a half bars long. I can’t think of any other pop songs with that phrase length - much less any huge hits

The third oddity (and we are still only five seconds into the song so far) is the measure of 2/4 in the line “because she loves me so and this I know for sure” - it’s under the words “know for”. Normal pop songs stay in 4/4 time all the way through. The Beatles sometimes used bars of 2/4 and other metrical asymmetry, but they did it at the ends of phrases, not in the middle of them. This is certainly not the kind of thing that pop and hip-hop artists often do. Also, a normal pop song’s verse consists of phrases that are four bars long. In Hey Ya!, the phrases are five and a half bars long. I can’t think of any other pop songs with that phrase length, much less any huge hits.

Compared to the meter and phrasing, the chords are practically pedestrian, but they are plenty strange too: a loop of G, C, D and E. There is no key that all of these chords belong to, and your guess is as good as mine whether G or E is the tonic. They are all easy to play on the guitar, and I assume this is how André discovered them. They don’t sound bad at all, but they defy easy analysis.

I won’t go through every unconventional choice in the rest of the song; that would be a book, not a column. I know a lot of OutKast fans are dismayed that the group’s biggest hit by far isn’t even a rap song, and that it doesn’t include Big Boi. But what can you do? The song is undeniable. After you read this, you will probably be walking around mumbling “shake it, shake it like a Polaroid picture” uncontrollably to yourself; I know I have been as I wrote this. The peculiarity and the power are inseparable.

4. Beyoncé - Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It)

In no way am I suggesting that this song is imperfect. It’s completely perfect! Beyoncé does not make mistakes. She does, however, sometimes make counterintuitive choices, and this song includes a few of them.

Listen to the first line of the song, “All the single ladies”. Is the downbeat on “single” or “ladies”? I suspect that Tricky Stewart and The-Dream intended it to be “ladies”, but Beyoncé heard it as “single”, and who would have the nerve to tell her that she is hearing something wrong? If that’s where she hears it, then it’s the right beat. But this means that the song starts with a bar of three, which wrong-foots me every time. The same thing happens coming out of the bridge, after the line “like a ghost, I’ll be gone.” With the downbeat on “single” rather than “ladies”, the bridge is eleven-and-three-quarters bars long rather than the immensely more conventional twelve.

Also, which part of this song is the chorus? Is it “All the single ladies”? Is it “If you like it then you should have put a ring on it”? Is it “Woah-oh-oh”? I always pose that question to my students when we are talking about form and structure, and there is never any consensus. Maybe the song has three choruses! Maybe it has one very long chorus with multiple different sections! Maybe I’m overthinking all this and it doesn’t matter! It does affect your listening experience, though; the signposts that you unconsciously use to keep track of where you are in the song aren't where you expect them to be.

The last unconventional feature of Single Ladies is its harmony. The song is in E major, and for its first 50 seconds, every note you hear comes from the E major scale. But then the synth and the backing vocals start hitting the note C, the flat sixth. This is not from E major at all; it implies E minor instead. It’s not that unusual for a major song to borrow chords from the parallel minor key, but that isn’t what’s happening here. Instead, Single Ladies uses that minor sixth from E minor and the first through fifth from E major at the same time. This implies an exotic jazz scale called Mixolydian flat sixth, and it’s very far from typical for a pop banger.

5. Taylor Swift - Shake It Off

This is the least weird of any of the songs on my list, but it’s exactly because it’s so by-the-book that its one weird part jumps out. I’m referring to the end of the spoken word bridge, which is a bar too long. This would not, in and of itself, such a big deal, but up until the bridge, every section of the song has been four or eight bars long, as predictable as clockwork.

The first half of the bridge (“Hey hey hey, just think…) is four bars long, as usual. And then the second half (“My ex-man brought his new girlfriend…”) is five bars long. The extra bar comes after “shake shake shake” and before the “Yeah-eah, ooh” leading into the last chorus. To further destabilize your sense of what is going on, Taylor slows down a little in the extra bar, so musical time seems to completely grind to a halt.

I have seen a lot of people try to dance to Shake It Off, and the extra bar throws them out of whack every time

I have seen a lot of people try to dance to Shake It Off, and the extra bar throws them out of whack every time. I have to assume that the effect was deliberate; like Beyoncé, Taylor Swift is not the kind of artist who leaves a decision unexamined. Is this song such a reliable standby for bar mitzvah DJs in spite of the odd bar, or maybe in part because of it? Is that the awkward corner that gives the rest of the tune a shape?

Here’s what I take away from all this. Songs are like people. You might naively think that if you want people to like you, then you should try to be as likeable as possible. Usually, that is true. But the most popular, famous and charismatic people are not necessarily likeable. They tend to be a little full of themselves, a little quirky, a little difficult. So it is with the biggest songs.