At the tender age of 14, Greg LeMond started cycling in Nevada just to “get in shape for skiing”. After only a fortnight he won his first race, but his choice of outfit attracted some dirty looks. “I showed up to my first race [in 1976] riding a yellow Cinelli bike and in a yellow jersey,” the American tells me by phone. “In my second race, my friend looked at me with such disgust, and I was wondering why. Ten days later I beat him, it broke the ice, and he said: ‘I gotta tell you: you don’t wear the yellow jersey’. When he explained why, I responded, ‘What’s the Tour de France?’”

A decade later, LeMond not only knew the Tour de France intimately but justified that early yellow jersey. As the first American and non-European to win the yellow jersey, LeMond would win two more maillots jaunes, including one in 1989 by a margin of eight seconds.

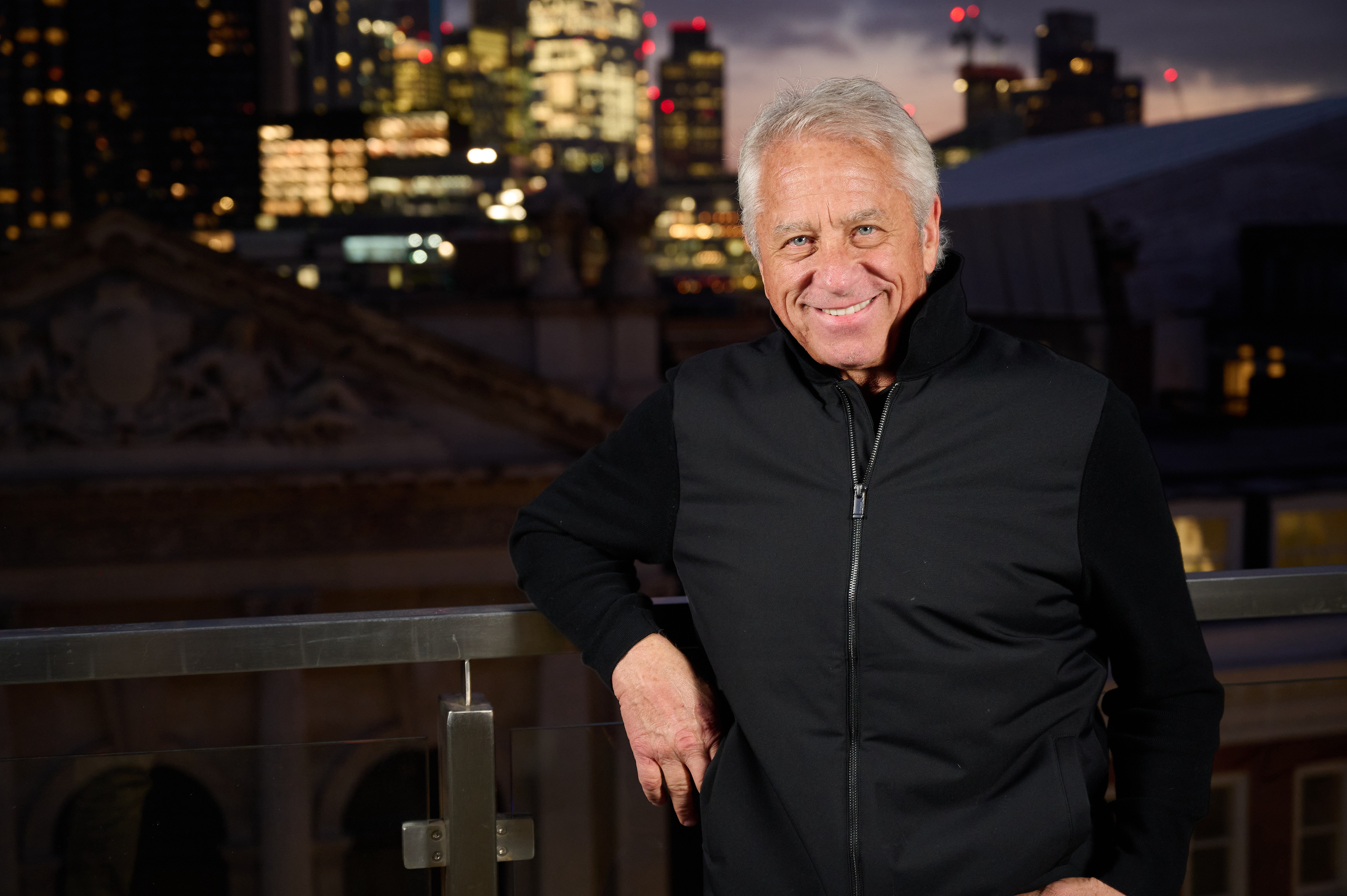

He is deserving of Cycling Weekly’s 2024 Lifetime Achievement Award for a multitude of reasons. He has set many records through his career – and not only in cycling; in 1991 he found himself in the world record books for catching a four-pound smallmouth bass during a fly fishing trip. He is also famed for astonishing comebacks, radical modifications and innovations that have shaped bike design, and regular outspoken tirades against what he believes was a doping culture that denied him even more Tours.

Tour dreams

“Three or four times a year, I still dream about riding the Tour. I wake up and say to myself, ‘What am I thinking? I’m 63 and double the weight of the pros’,” he laughs. “I can’t imagine any other sport that has the same speed, intensity and competitiveness of cycling. I have a love-hate relationship with it because of the drugs and the closed-minded culture, but what’s more exciting than racing the Tour de France? I’m so glad I found cycling.”

LeMond’s first forays into cycling were a breeze. “I won pretty much every race I entered as a junior, 11 in a row,” he says. He was moved up an age category, but still things were too easy. The USA’s national team coach, Eddie Boryseicz, found himself working with “a diamond, a clear diamond” who was brimming with a youthful naivety that supercharged his ambitions. “I didn’t know anything about the sport,” says LeMond. “I was discovering so much, including the Tour de France which was apparently this mythical race. People were telling me that Eddy Merckx was the God, but they all had this idea that Americans weren’t good enough.” In 1979, aged 18, LeMond became junior world champion, and with characteristic optimism asked his teammates: “Why can’t I win the Tour?”

Renault-Elf-Gitane, the team of two-time Tour winner Bernaud Hinault, gave a 19-year-old LeMond his first professional contract in 1981, and within six months he finished third at the Critérium du Dauphiné. A year on, he finished second in the World Championships and won the Tour de l’Avenir by 10 minutes. He was the complete package: he could climb, time trial, sprint, and he recovered fast. Europe was getting excited about the young man they’d later coin LeMonster. In 1983, he upgraded silver to gold in the Worlds, becoming the first American male to wear the rainbow bands on the road. He was only 22.

Though his aspirations soared, it was his teammates Hinault and Laurent Fignon who won the next four Tours. Tensions rose – LeMond was hungry for Tour success, as he had demonstrated by finishing third and winning the young rider classification in his debut in 1984. “We had multiple leaders at Renault and it meant sacrificing my own personal goals and ambitions to support the team,” he says. “Before I turned pro, I wanted to win every race, so when I couldn’t do that and was working for another guy, it was normal to look for another way.”

LeMond was convinced to join La Vie Claire in 1985, the team that wore one of cycling’s most iconic jersey designs and which was the home of his former teammate Hinault. The ambitious rising star would get his own chance to win the Tour, but first he had to help Hinault win his fifth. The sweetener? LeMond became the first cyclist to sign a million dollar contract. He helped The Badger win his cinquième Tour, while feeling confident he could have won the race himself. “I was way too loyal as a teammate in that 1985 Tour,” he recalls. “I should have been more selfish and less naïve,” – a reference to how his team prevented him from attacking an injured and weakened Hinault in the final week.

Hinault promised to repay LeMond and help him win his maiden Tour in 1986, but by the 12th stage the Frenchman’s lead over the American stood at 5:25. Remarkably, and despite bitter infighting, LeMond overturned the deficit to beat Hinault by more than three minutes. History was made. France, in love with L’Americain, courted and chased the forthcoming American attention and dollar. With one win, he had changed cycling forever. “Physically, I was at my top in ‘85 and ‘86,” he says. The sport was entering the LeMond era. Until it wasn’t.

Overcoming adversity

In the spring of 1987, LeMond was accidentally shot by his brother-in-law with around 60 pellets while they were turkey hunting in California. The Tour champion lost 70% of his blood, was 20 minutes away from bleeding to death, and suffered lead poisoning that “left me basically anaemic” and which he later blamed for his non-life-threatening leukaemia diagnosis in 2022.

He made a stuttering return to cycling at the end of 1987, convincing no one, not even himself, that he could return to Tour-winning form. “I went from the very best to one of the very worst,” he says. He departed Dutch team PDM after only one year, having become aware of teammates doping.

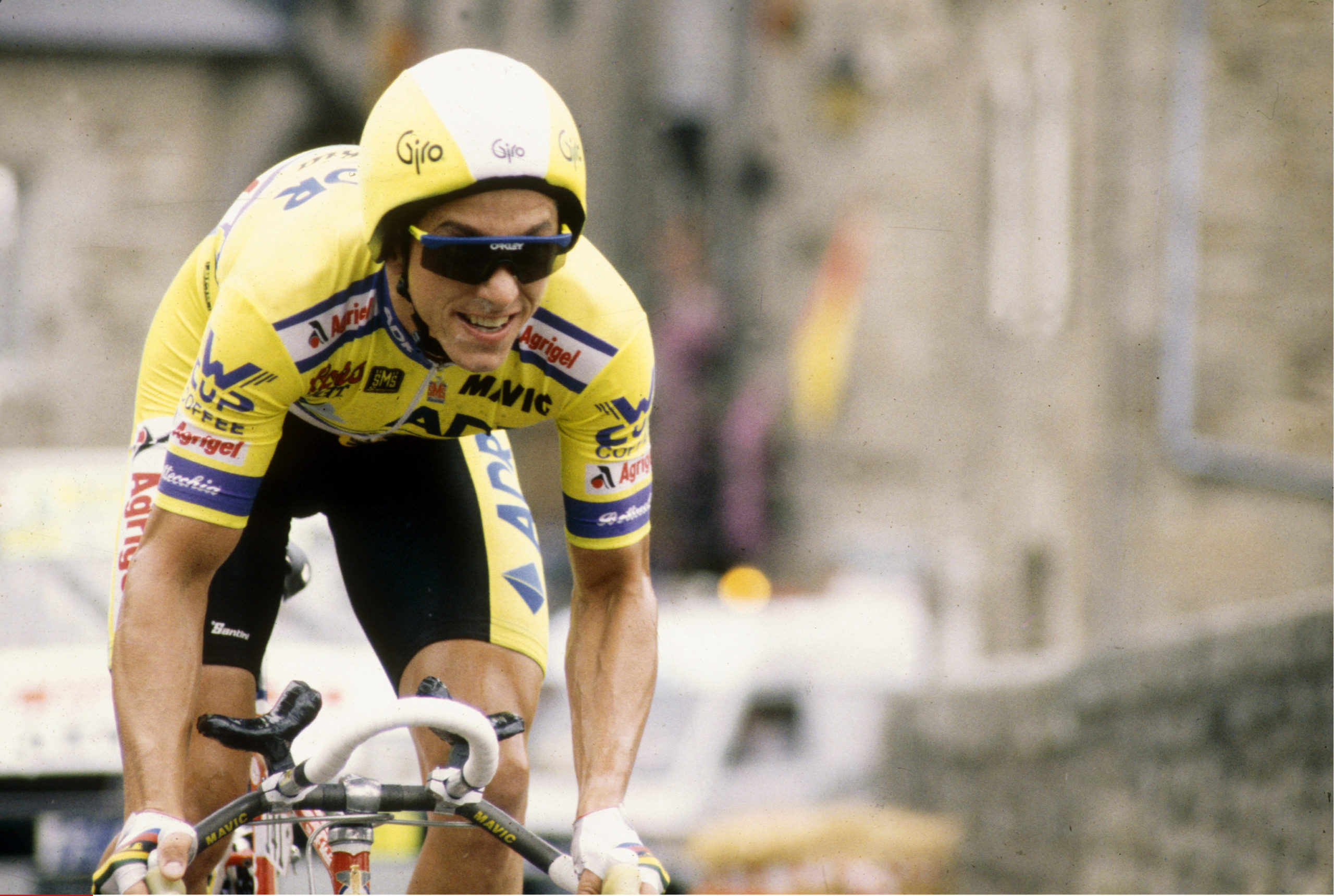

“It’s never really been written what my wife Kathy and I went through after I got shot,” LeMond says. “The suffering, the lack of hope, the dark days, every race saying I’m going to come back but then cracking, two PDM riders testing positive. It was our worst nightmare.” The only team offering to salvage his career was ADR, who he describes as “a great team, but the lowest budget ever seen in cycling – no one got paid”. But that wouldn’t matter, as what he did in 1989 is the stuff of legend.

A month after disappointing at the Giro d’Italia – “I had massive allergies and didn’t think I’d ever get back to where I was in ‘86,” he says – he arrived at the Tour with no expectation of riding for the GC. Yet he shocked the world with a captivating, nail-biting and flip-flopping battle with former teammate Fignon.

Ultimately LeMond erased the Frenchman’s 50-second advantage in a final-day time trial to improbably win by eight seconds. “To go from the lows of the Giro to winning the Tour in six weeks is about as fun as you can get,” LeMond smiles.

His final-stage triumph, which spawned countless books and films, was partly attributed to LeMond’s aero tri-bars, rear disc wheel, aero helmet and aerodynamic position honed in the wind tunnel. The American was ahead of his time, a pioneer, the first man to win the Tour on a carbon fibre frame bike; it was no surprise he founded his own bike brand, LeMond Bicycles.

“Coming from outside the sport, I had a lot of different ideas,” he says. “The way they did things was set in stone, but I questioned everything and was very open-minded. I do believe I played a big role in changing the old, traditional part of cycling and bringing it into the modern era.” He also devoured training literature and was one of the first to use a power meter. “Part of my DNA was understanding training physiologically,” he says, though this is not to suggest he found shortcuts – as he famously quipped, “it never gets easier; you just get faster.”

LeMond followed up that memorable 1989 Tour win with his second rainbow jersey and then his third Tour the year after. His reign at the top was coming to an end, however. In 1991, the Spaniard Miguel Induráin won his first Tour, and would dominate the race for the next four years. LeMond retired in 1994, but is convinced he could have won more had it not been for infiltration of blood doping into the sport. “Part of my heart aches that I didn’t get to have a career that wasn’t less hampered by injuries and the beginning of the EPO era,” he says.

The American insists he never doped, and he has consistently railed against the use of performance enhancing drugs, including a lengthy public spat with Lance Armstrong. Why did he position himself as cycling’s Mr Anti-Doping? “I just had to get into that position,” he says. “It really blew my mind that the Armstrong era was even worse than the late-Nineties.” His sadness about the dark reality of the sport played on his mind while working as a commentator on Eurosport. “I loved it, but it was hard to be enthusiastic for certain people who I had inside info on. It was painful.”

Reflecting on his own racing achievements, LeMond says he has “mixed emotions” over a nagging sense he could have achieved more. “I was the first American to win the Tour but I had an accident that took me out of my prime,” he says. “I also dreamt of winning five Tours, which logically I should have. I truly believe without EPO I would have won in 1991 and 1992.”

Imponderables aside, the LeMond of today, a man who fundamentally altered so much in cycling, has not lost his passion for pro racing. “It’s a magical sport and I’ll never get out of it because it’s in my blood.”