Amplifying underreported perspectives, fostering a sense of belonging, nurturing talent and resisting the status quo. These are the critical functions of the Black press in Britain.

While trends may wane and things change with the passage of time, the need for media platforms that highlight Black experiences has been ever-constant.

The Black press in Britain is at least a century old, always standing apart from the mainstream hub and typically positioned adjacent to Fleet Street while running alongside the movement for racial equality.

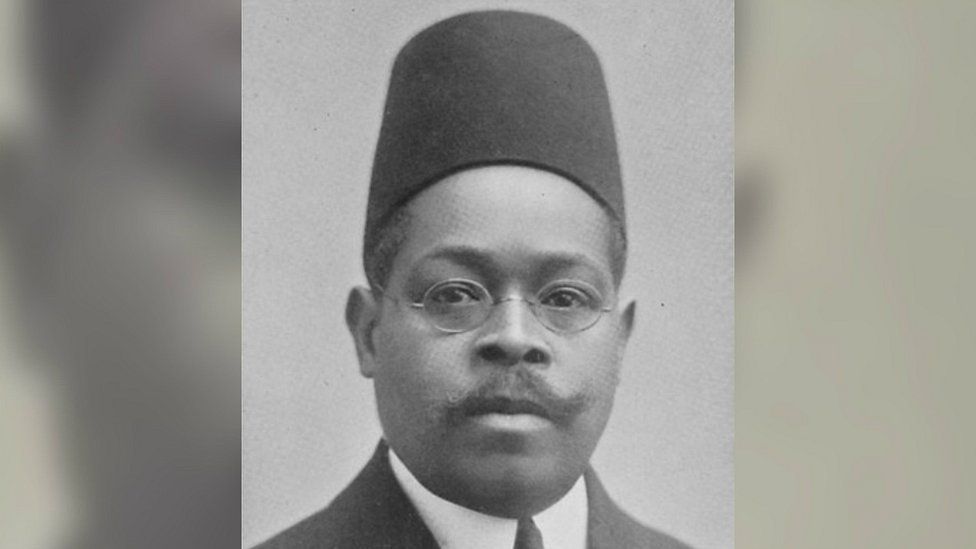

Britain’s first Black “campaigning” journal is thought to be The African Times and Orient Review of 1912.

Founded and edited by Dusé Mohamed Ali, a Sudanese-Egyptian Muslim activist, it published essays by writers such as activist Marcus Garvey and political dispatches focusing on events within British colonies. It attracted readers from Britain, the US, Asia, and the Caribbean.

It also ran a regular ‘man of the month’ fixture and in April 1920, featured Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali polymath, after returning his knighthood to Buckingham Palace on principle, according to the British Newspaper Archive, after British soldiers murdered hundreds of peaceful protestors in the Amritsar Massacre in 1919.

The Review demonstrated the need to follow key issues, namely the struggle for equitable opportunities and laudable achievements among minoritised communities, at the seat of the British Empire and give the wider public insight into this.

It was anti-colonial and radical.

Similarly, its contemporary outlet which circulated around 1915 for four years, the African Telegraph and Gold Coast Mirror, edited by Sierra Leonean journalist John Eldred Taylor, examined issues around the empire, maintaining a focus on West Africa.

The Voice newspaper, Britain’s longest-running Black publication, was founded by Val McCalla in 1982. It celebrated its 40th anniversary this year through a collaboration with the British monarchy, with King Charles III - who was then the Prince of Wales - becoming guest editor of the September 2022 issue.

“The need for strong independent Black newspapers has never been more evident. A single newspaper clearly isn’t enough,” Michael Eboda, former editor at the New Nation newspaper, once The Voice’s competitor, writes in the recently released book, The Voice: 40 Years of Black British Lives.

“But as The Voice soldiers on, perhaps we should be grateful for small mercies,” Mr Eboda added.

Mr Eboda now oversees the annual Powerlist and Future Leaders publications which, like the New Nation, exclusively focuses on Black achievement. Launched in 1996, the New Nation was a weekly title founded by Tetteh Kofi.

Academic and author Nicola Rollock, added: “In a society in which we are otherwise rendered invisible - or only made visible when deemed a problem - the Black British press has been essential to determining and reflecting who we are on our terms.

“Our cultures, identities, norms and desires - infused with tales of ‘back home’ - are captured not just in articles, interviews and advertisements but in the names of the journalists and editors who have graced their pages.

“This is the news - our news - documented for the present and, crucially, as an enduring legacy for generations to come. Therein lies the importance of the Black press.”

The Weekly Gleaner newspaper is an all-too-often overlooked media entity in Britain, particularly in the context of national media discourse.

Launched in London amid the Windrush migration in 1951, it sits under the Gleaner Company banner and caters for the now ‘older’ generation of Caribbean migrants who settled and set up life in Britain.

It quickly became a staple source of news of goings-on ‘back home’ and across the diaspora. It has endured ever since, marginally broadening its focus to UK-based news and punching, despite waning circulation.

The Caribbean News, published by the London branch of the Caribbean Labour Congress, was launched in 1952 to meet similar needs but folded in 1956.

Its closure came after race riots and the imposition of colour bars - a racist policy that prevented Black people from getting jobs - within various British workplaces.

“In a society with a growing diverse population with different ethnic backgrounds, the British press remains stubbornly white,” George Ruddock, of the Weekly Gleaner, said, adding that independent media platforms are vital in ensuring press freedom remains an important pillar of democracy.

According to research by City University, just 0.4 per cent of British journalists are Muslim, compared with almost 5 per cent of the UK population, and only 0.2 per cent are Black, compared with 3 per cent overall.

By contrast, some 94 per cent of journalists are white, compared with 86 per cent of the population, the National Council for the Training of Journalists has found.

Over the course of a week in mid-July, at the height of the global resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, research showed that not a single story by a Black reporter appeared on the front page of a UK newspaper.

This was despite the UK media industry’s ongoing promises to become more inclusive.

In the aftermath of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s famous Oprah 2021 interview, where the royal couple took issue with what they saw as racist treatment of the Duchess of Sussex by UK newspapers, the Society of Editors issued a statement denying that the media industry had a racism problem, yielding immense backlash.

Even if the mainstream media does diversify, the need for Black press will always be required.

“It’s great that newsrooms want to tell more diverse stories but often they are still delivered with a white gaze,” Afua Hagan, veteran journalist, told The Independent.

“How many Black news editors or people higher up in news organisations do we have? Not enough - that’s for sure. That is why it’s so important that we maintain and support Black media outlets.”

Ms Hagan, who has edited a number of Black titles in the UK including Black Hair magazine, Pride Magazine and Glam Africa Magazine, also said finances and capital are huge obstacles when it comes to sustaining Black publications.

“It can be so hard to get ‘mainstream’ advertisers to realise the value of advertising with the Black press and often they are the ones with the biggest budgets.”

Public Relations companies also have a lot to answer for, Ms Hagan added.

“It’s also difficult when working with PRs to get them to take Black press seriously as well. Getting interviews with prominent Black celebrities and notable people can be like The Hunger Games.

“Often, it’s the PRs who act as gatekeepers and [it’s] not the celebrities themselves who don’t want to speak to the Black press.”

With that said, people aren’t waiting around for representation nowadays - any more than they were previously.

Serlina Boyd – a London mother of two – launched two magazines Cocoa Boy and Cocoa Girl in 2020 to inspire Black children after ignoring advice that “no one would be interested”.

“You cannot allow someone to tell you ‘no’ when you want to realise your dreams,” Mrs Boyd told The Independent in July. “Just go for it – step out and pursue whatever you want to do.”

The media entrepreneur recently announced the launch of Cocoa magazine, the adult title to her children’s magazines, Britain’s newest glossy Black title.

Media platforms such as Gal-Dem, founded by Liv Little, and Black Ballad have become household staples across Britain, particularly among millennial and generation X Black women, who have long felt let down by parts of the UK mainstream media.

Black Ballad founder Tobi Oredein launched her lifestyle brand from a “place of frustration” after struggling to get a permanent job in white-dominated mainstream media.

”For far too long society has and still does ignore the challenges, trials and triumphs of Black Britons. Black media not only acknowledges these moments but understands and reports with nuance and empathy about Black Britons,” Ms Oredein, who runs the platform with her husband Bola Awoniyi, told The Independent.

“Black media and press report on the issues that are important to our community, and in doing so, document Black history more fairly but also in a way where we have agency and not as passive supporting props to white people.”

Years ago in 1979, Root magazine, co-founded by Neil Kenlock was launched as Britain’s first Black lifestyle publication. It was later followed by Pride Magazine in 1991 which, at its peak, circulated 30,000 copies per month, and is still running.

The Black press is born out of underrepresentation, a desire to address lack of mainstream inclusion and racial tension.

Just as the Review was sparked by the very first Universal Races Conference, anti-racism crisis talks held at the University of London in 1911, The Voice followed the riots in Brixton.

There’s a rich, enduring history of Black titles in Britain from The Caribbean Times, launched in 1981 by Arif Ali, to Black Briton in 1991 launched by Joseph Harker, now The Guardian’s first diversity executive.

There’s also the Weekly Journal launched by The Voice as ‘a spoiler’ to Black Briton and The West Indian Gazette by Claudia Jones, the first Black woman newspaper editor, and activist Abimanya Machanda, in 1958. All of these titles were relatively short-lived and disbanded following financial challenges.

The Black press encompasses much more than just words on a page. For many people, it signifies a sense of belonging.

“Black British journalism matters to me because it’s given me a community,” journalist and author Charlie Brinkurst-Cuff wrote in Black British Lives Matter, a collection of essays edited by Lenny Henry and Marcus Ryder last year. “It matters to the world because we are the only people who can tell our stories. And, man, our stories. They deserve to be told.”

Speaking to The Independent, journalist Michelle Martin described how the Black press gave her the “confidence to feel comfortable in her skin in this country” while shaping her career.

“Growing up, we didn’t see many Black people in the mainstream press so having something that I could call my own and relate to in this country meant to so much to me,” Ms Martin, former editor at The Voice and New Nation said.

“It’s the reason why I became a journalist. I wanted a safe space, to convey perspectives, thoughts and feelings that my family and friends could understand and relate to.

“The Black press often champions causes that are overlooked; that’s what I love about it. Working there was the happiest time in my career and those titles will always have a place in my heart. I think that was the happiest time in my career.”

And the Black press is an institution, Ms Martin points out.

“I hope it continues to give young Black people the springboard that I have. There are loads of people who have come through the Black press who have done extremely well” from Afua Hirsch and Trevor Phillips to Brenda Emmanus and Henry Bonsu.

In recent years, newer media publications that report Black news have emerged online and locally from Jus Jah Magazine, which serves Rastafarian communities in particular, Melan Magazine and GRM Daily to Instagram-based platforms like The Shade Borough and UK Gossip TV.

Joy Sigaud, publisher of the annual Editions Black History Month magazine, is calling for more national Black media publications. After all, there’s plenty of room.

“With some two million people of varying ages, affiliations and backgrounds, it simply not possible for just one or two specialised publications to cover the broad range of needs and interests of these diverse diasporas,” Ms Sigaud, who launched her magazine in 2019, told The Independent.

“I am looking forward to seeing more pragmatic sustainable targeted investment in this significant and traditionally overlooked sector.”

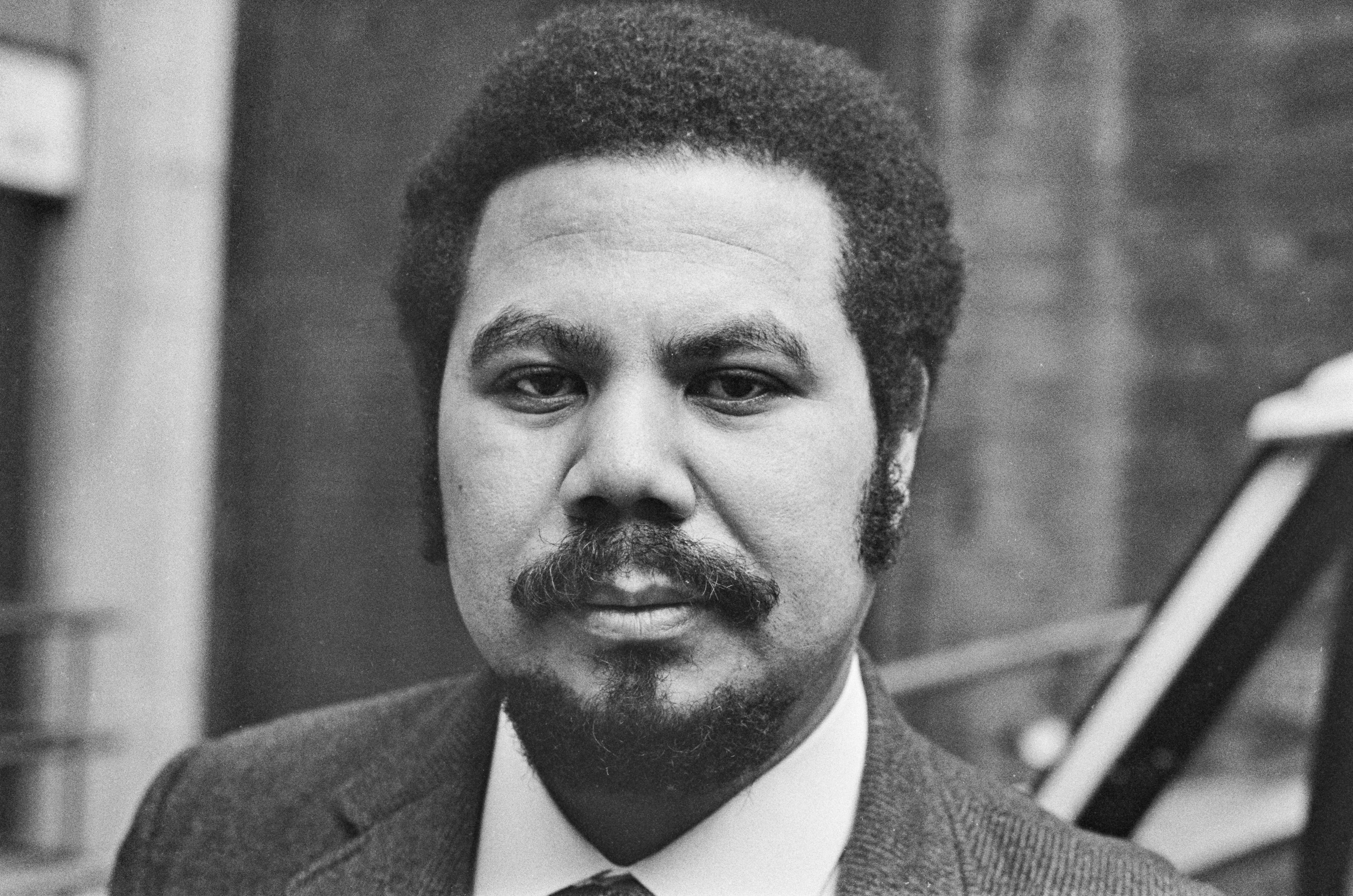

Lionel Morrison, the first Black president of the National Union of Journalists, succinctly broke down the significance of the Black press in his study of the topic, almost 20 years ago.

“Originating both because and in spite of adversity, the Black press has had a rich, varied, volatile history. It gave Blacks and Asians a voice of their own and an opportunity only to answer the attacks printed in the mainstream (white) press but to read articles on Black accomplishments, marriages and deaths that the white press of the day ignored,” Mr Morrison wrote in A Century of Black Journalism in Britain (2003).

“It is the story of the persistent struggle against widespread prejudice, racism and discrimination, mirrored by stereotyping and rejection in the conventional wide media.”