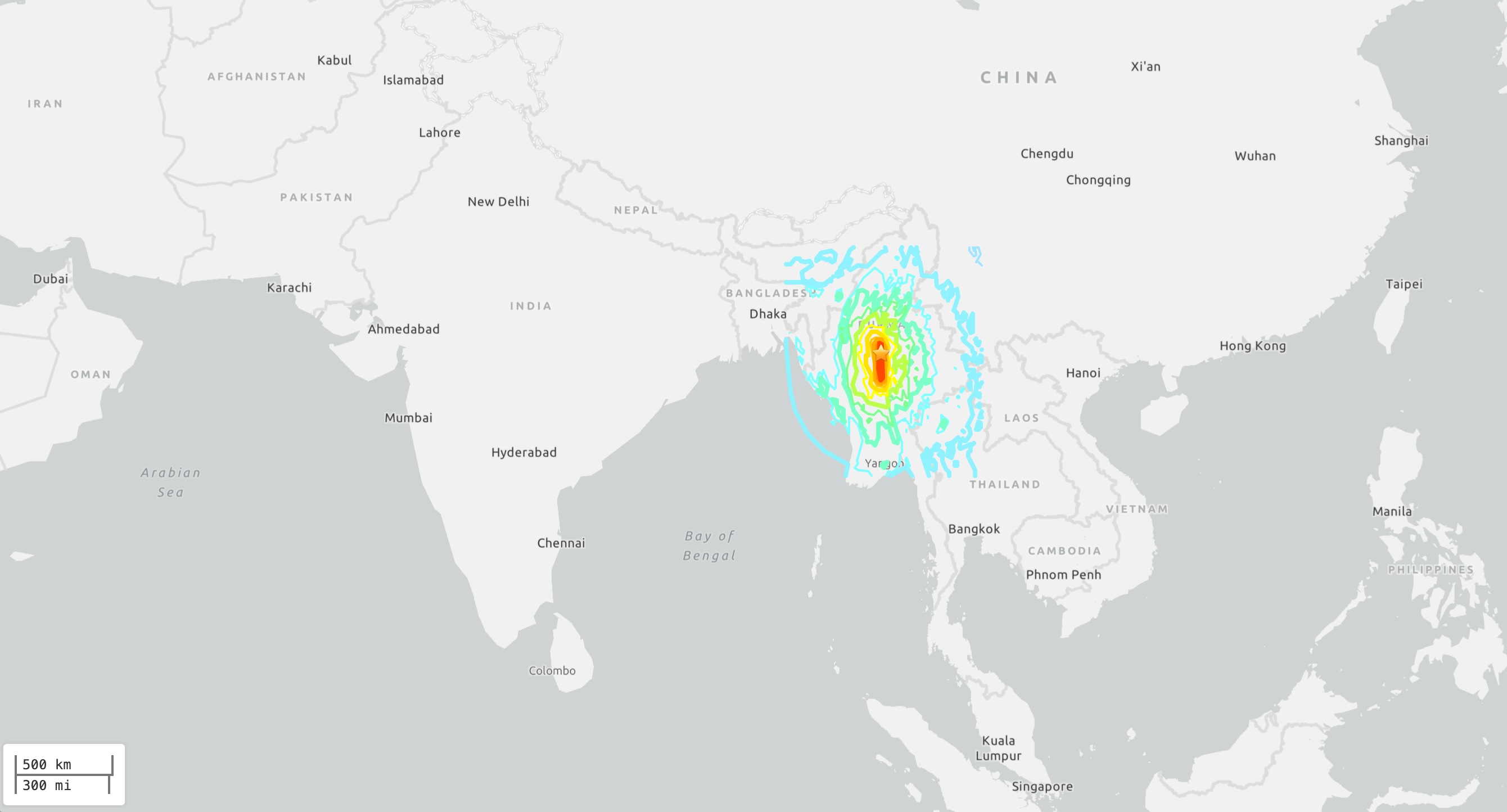

A powerful magnitude 7.7 earthquake hit central Myanmar (formerly Burma) Friday (March 28), shaking Mandalay, the country's second-largest city, as well as nearby countries, including China and Thailand, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reported.

The shallow earthquake struck at 12:50 p.m. local time (2:20 a.m. EDT) at a depth of about 6.2 miles (10 kilometers), the USGS reported. Just 12 minutes later, a magnitude 6.7 earthquake at the same depth shook south of the first one, and later that day, nine smaller earthquakes, ranging from magnitude 4.4 to 4.9, also hit the region.

At least 144 people were killed in the earthquakes, and 732 were injured, Myanmar's military junta said, according to The Washington Post. A monastery and multiple buildings also collapsed in Myanmar. In Bangkok, at least 10 people died when a 33-story high-rise under construction fell down; Thai authorities also said 16 people were injured and 101 were missing, the Associated Press reported.

Although Bangkok was "well removed from where the faulting was" in Myanmar, "it's a very big earthquake and it's not really surprising it would have been felt for that amount of distance," Gregory Beroza, a professor of geophysics at Stanford University, told Live Science.

The earthquakes struck at the Sagaing Fault, which runs north-south and spans nearly 1,000 miles (1,600 km) through Myanmar toward the Andaman Sea. Earthquakes that occur on this fault are known strike-slip quakes, in which one block of land moves horizontally past a block of land on the other side of the fault, according to the USGS. This is a similar setup as the San Andreas Fault in California, which is also a strike-slip fault.

Related: Scientists find hidden mechanism that could explain how earthquakes 'ignite'

Myanmar, which is just south of the Himalayas, is a seismically active region and known for its big earthquakes, Ben van der Pluijm, a professor emeritus of geology at the University of Michigan, told Live Science.

"The reason for that is that the continent of India sits on the Indian Plate. And the Indian Plate has been moving northward for around 100 million years," van der Pluijm said. "But around 40 million years ago or so, India connected with the Eurasian Plate and kept on traveling northwards into the Eurasian Plate." Over millions of years, that collision helped create the Himalayas.

Even today, the Indian Plate is still moving northward, into the Eurasian plate. That motion "is what accumulated the energy that gets released in earthquakes like today's earthquakes in Southeastern Asia," van der Pluijm said.

Today's magnitude 7.7 earthquake was so big that it wouldn't be surprising if the ground were displaced several meters horizontally, van der Pluijm added.

"This is a very big earthquake," he said. "We don't have many of these."

Because these earthquakes were so shallow, they could be compared to the magnitude 7.8 and 7.5 earthquakes that struck Turkey in 2023 and caused widespread death and damage, said Jeffrey Park, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences who specializes in earthquakes and Earth structure at Yale University.

"We should expect the same kind of damage report and also loss of life from this earthquake because it's a shallow earthquake that's in a heavily populated area of Burma," Park told Live Science.

Since 1900, the region has had six other magnitude 7 or greater big strike-slip earthquakes within about 155 miles (250 km) of today's earthquake, according to the USGS. The most recent one, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake in January 1990, caused 32 buildings to collapse. An even bigger one — a magnitude 7.9 — shook south of today's earthquake epicenter in February 1912.