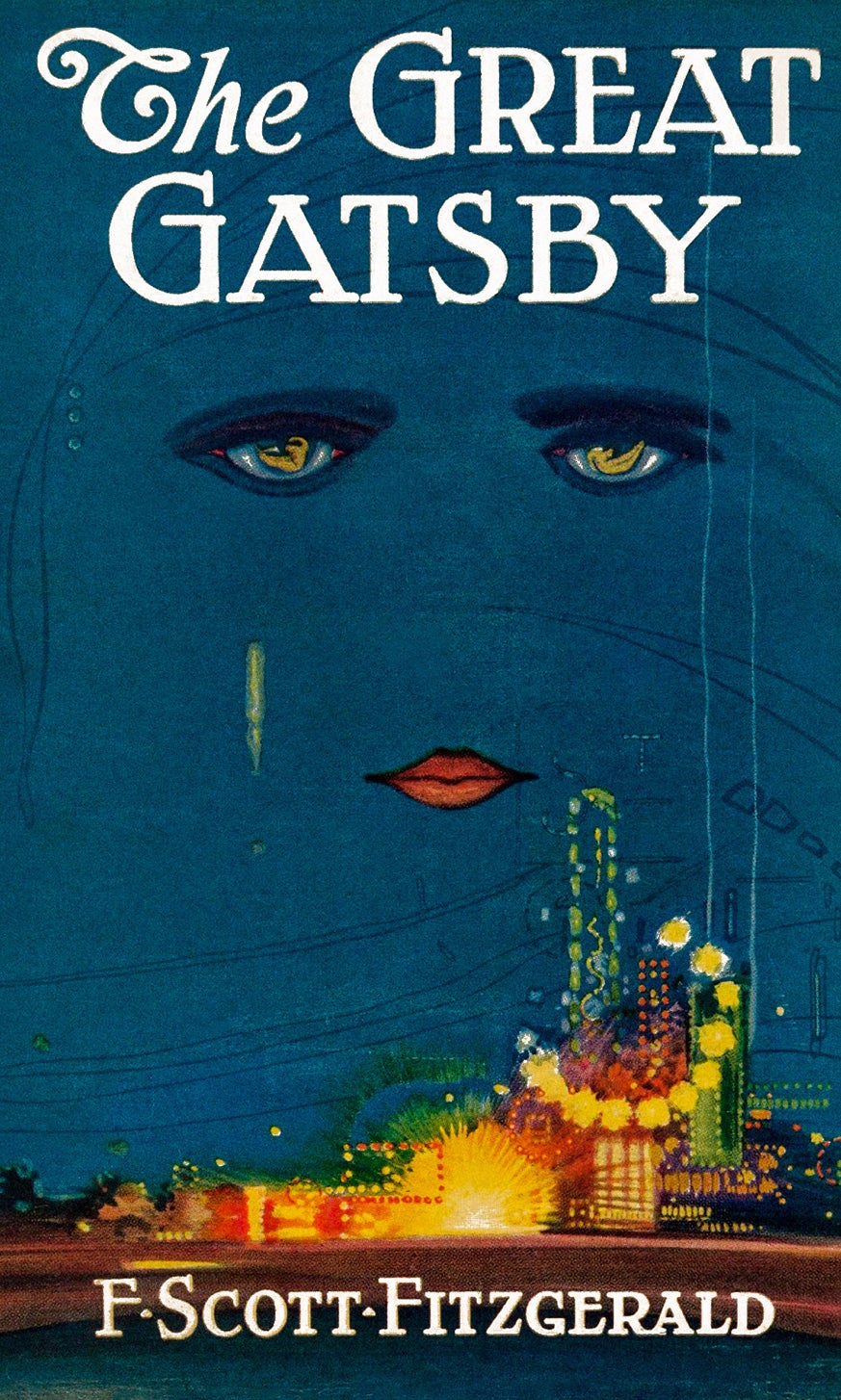

In my house, there are two copies of F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, which turns 100 this week. The first is my schoolboy edition, rendered almost illegible by the quantity of doodles in the margins: old-fashioned motorcars, champagne flutes, looming pairs of eyes. On the second, a gormless stock photo flapper girl – feathers in her hair, lace gloves covering her hands – stares back at me, insisting, seemingly, on a glamorous vision of interwar America. On the inside of the jacket, a glued-on advert tells me this edition was distributed as part of a scheme to promote laser eye surgery.

The Great Gatsby is a slippery text. It means different things to different people. To some it is a monolith of American literature – a key contender in the Great American Novel sweepstakes – whereas, to others, it has become a cartoonish portrait of a bygone era. Some read it as an excoriation of materialism, others as a vindication of excess. For some it is sibylline, for others, passé.

At its essence is a simple, almost parabolic, story. The narrator, Nick Carraway, has moved into a cottage in the grounds of a vast Long Island mansion. Over the summer, decadent parties explode through his neighbour’s grounds, and Nick watches on until an invite arrives. “I believe that on the first night I went to Gatsby’s house,” he tells us, “I was one of the few guests who had actually been invited.” His neighbour is Jay Gatsby – a shady bootlegger who has amassed a vast wealth to try, perhaps, to win back his first love, Daisy, from her boorish old money husband Tom Buchanan. The Buchanans live in a mirror estate, across the sound, and Nick finds himself employed as an emissary between the two camps, as the novel builds to its tragic conclusion. Upon release, the book was heralded by critics, and by the 1970s it started to assume that Great American Novel crown, a title that has preoccupied novelists from Herman Melville to Jonathan Franzen.

Like many great books, something of its power has been lost in the fog of its own mystique. It is packed with fabulous lines that have entered the popular lexicon. “In my younger and more vulnerable days,” the novel begins, an opening that stands alongside Pride & Prejudice’s first line for sheer public cut through. It’s matched by its equally famous (and brilliant) final line: “And so we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” For a novel written in the 1920s – when the literary establishment was on the brink of modernism, a movement that would strip language right back – The Great Gatsby’s prose is as opulent as the wardrobe of its central characters.

It is precision engineered. I think all the time of the “owl-eyed” man in Gatsby’s library, delivering to Nick his verdict on their host’s artifice. “What realism! Knew when to stop too – didn’t cut the pages.” And perhaps because Fitzgerald’s writing is psychologically virtuosic in a way that some of his great peers avoided (“Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself” would be an easy line to write but an impossible one to replicate), Gatsby has often, in its first century on earth, been sidelined. It is better remembered, by some, for its film versions: Robert Redford and Mia Farrow swooning in a 1974 adaptation written by Francis Ford Coppola, or Leonardo DiCaprio seducing Carey Mulligan in Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 version, which was released to popcorn-munching audiences in full 3D. In 3D, it seemed, so this allegory for the frailty of American capitalism would really slap you in the face.

Right now, in London, you can visit an immersive Gatsby experience (a “world of red-hot rhythms, bootleg liquor, and pure jazz age self-indulgence”) or watch an all-singing, all-dancing adaptation of the novel at the London Coliseum. There are Great Gatsby-themed escape rooms, Great Gatsby-infused cocktail menus, a Great Gatsby-inspired suite at New York’s Plaza Hotel. You can buy Gatsby candles, a Gatsby board game, a Gatsby range from Tiffany’s, complete with a Savoy headband inlaid with diamonds and “freshwater cultured pearls” (price on application). Taylor Swift – Miss Americana herself – has referenced Fitzgerald’s work in several songs, from “Happiness” (“I hope she’ll be a beautiful fool”) to “This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things”. “Bass beat rattling the chandelier,” the Pennsylvania-born singer-songwriter warbles. “Feelin’ so Gatsby for that whole year.”

Have we lost sight of the real Great Gatsby? Fitzgerald wrote the novel in Europe in the middle of the 1920s, a time of profound political upheaval. He completed the novel in Rome, a city mired by right-wing “squadristi” violence perpetrated in support of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini. Fitzgerald’s cultured émigré perch was not a naïve one: the broiling inequalities witnessed in countries like Italy and Germany, which would ultimately lead to the rise of fascism, are rendered starkly in his portrait of a divided America. Think of the paternal advice that opens the novel: “Whenever you feel like criticising anyone… remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages you’ve had.”

Wealth and moral decency are “parcelled out unequally at birth”, or so our narrator, who slyly gawps at the novel’s spectacles, tells us. On the latter, the book is equivocal; on the former it is emphatic. It was a period of historic excess for the United States, as the post-war economy roared, and America became the dominant world player. It was also a time of prohibition, a ban on the sale of alcohol, which created a two-tier dynamic where the rich partied with abandon, while the poor were imposed a dogmatic temperance. In this era, a gangster class emerged – of which Gatsby is an example – to fulfil the illegal demands of American boozers. It all corresponded to a peak, in the late 1920s, in American income inequality – a peak that wasn’t surpassed until 2007.

“They were careless people, Tom and Daisy,” comes the novel’s final judgment. “[T]hey smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness.” This final line was recently deployed as the epigraph – and title – of a tell-all memoir written by former Facebook exec, Sarah Wynn-Williams, to depict the grotesque culture to emerge at the Big Tech firm. In Wynn-Williams’ vision, a man like Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s founder and CEO, is a modern-day Buchanan: a symbol of the vast chasm of inequality and the reckless pursuit of excess. “[W]e’re living in the world that has been shaped by these people,” she concludes, “and their lethal carelessness.”

The iconography has changed. The tuxedos and flapper dresses have been replaced with a uniform of skin-tight T-shirts. Champagne (“served in glasses bigger than finger-bowls”) has been ditched in favour of life-extending protein shakes. Ostentatious bright yellow cars (the type that’s easy to pick out after a crime) have been replaced with anonymous black coupes connoting little more than the salary of their driver. But make no mistake: the 2020s are just as violently unequal as the 1920s that Fitzgerald was sketching in The Great Gatsby.

It’s clear that Gatsby was prescient. It was published in 1925, and the party continued, in America at least, until the Wall Street crash of 1929. There is little in the novel that predicts either that stock market collapse nor the decade-long depression that followed, and yet the novel’s feverish climate feels like a storm is about to break. The atmosphere is oppressive – “relentless beating heat” – set in a world hemmed in by smouldering ashes. Beyond the McMansions is a “fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills” and “grotesque gardens where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke”. It is a portrait of desolation to stand alongside post-apocalyptic visions like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Nevil Shute’s On the Beach.

And yet, Gatsby is resolutely pre-Apocalypse. That was Fitzgerald’s gift: to capture a moment pregnant with destructive forces, in real time. Fifteen years later, John Steinbeck would publish The Grapes of Wrath, another landmark novel about the American economy, written on the other side of the Great Depression. The miracle of The Great Gatsby, then, is that it’s a novel about an event that had yet to happen.

All the clues are there, a hundred years later, to suggest that The Great Gatsby has lost nothing of its ferocious currency. It is there when we affix our 3D glasses so that a jazz trumpet protrudes into our vision like a carnyx. It is there when we hand over £100 to attend a themed speakeasy populated by dead-eyed actors on minimum wage. And certainly, it’s there in our choice deployment of “carelessness” to describe our current billionaire oligarchy. All this time after Fitzgerald unleashed his vision on the world, it still strikes a note of warning. Famine must follow feast, shortage must follow glut, the Great Depression must follow the Roaring Twenties. But, like all prophetic tales, The Great Gatsby is doomed to be ignored.

What to read this April, from a very candid Doctor Who biography to five-star fiction

The sad decline of Gore Vidal, America’s most acerbic writer and fearsome feuder

Beatles biographer Ian Leslie on John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s ‘erotic’ bromance

Vanity Fair’s lavish Nineties era is enough to make any journalist today depressed

This book brings the grim horrors of London’s rental market to life

Decolonising Shakespeare makes no sense for this simple reason