Photographs by Brenda Ann Kenneally

“Boy crazy” was what people called it. “She was so boy crazy,” I would hear about my girlfriends. I never heard the reverse, that a boy was “girl crazy.” Girls having crushes, sneaking out at night to have fun: It seems innocent enough. But in my small, conservative town, a “wrong” choice at a young age could cut girls off from their future dreams, leaving them mired in despair.

Growing up in the ’90s in Clinton, Arkansas, all that my best friend, Darci Brawner, and I dreamed about was getting out. “I want to see new people and new places,” I wrote in my journal when I was 12. I wanted to move to California but would take “any state besides Oklahoma or Mississippi.” We wanted careers; we wanted to be rich and famous; we wanted to be far away. Boys and sex would only stop us, catch us, or so my mother had warned.

Clinton is the county seat of Van Buren County, Arkansas, and, with slightly more than 2,500 people, the biggest town in the area. It’s on the southern edge of the Ozarks, the hills we generously called mountains, situated in a valley where two big creeks come together in a Y. The county’s median household income in 2021 was $40,763. Almost everyone goes to an evangelical church, and in the halls of the town’s only high school, everyone knows everything about everyone else, or seems to: whom you dated, where you bought your clothes, how you acted on weekends, and even your destiny, inherited from the generations that came before you.

I moved away for college when I was 18. While I was gone, I heard updates: who was getting married, having children, getting divorced. I heard worse stories, about who was on drugs, who’d been arrested and sent to prison, who was in rehab, who was in rehab again. Who had died. By the time I was a journalist writing about rural poverty in my mid-30s, I’d seen studies and data that helped me put the stories from home in context. One of the most alarming trends emerged about a decade ago.

In 2012, a team of population-health experts at the University of Illinois at Chicago found that white women who did not graduate from high school were dying about five years younger than such women had a generation before—at about 73 years instead of 78. Their white male counterparts were dying three years younger. From 2014 to 2017, the decline in life expectancy in the U.S., driven largely by the drop among the least-educated Americans, was the longest and most sustained in 100 years.

They weren’t just dying from so-called deaths of despair—from drugs or suicide. Many of them were also dying from cancer, heart disease, or respiratory diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer, a 2022 study found—even as these conditions became less deadly for the rest of the population.

Women in Clinton and places like it, women I’d grown up with, women I knew, were losing years of their life. What was going on?

I returned to Arkansas more and more, trying to reconnect to my hometown, looking for answers. In 2015, on a visit home, Darci contacted me out of the blue. We’d once been as close as sisters, but that spring was only the second time I’d heard from her in the nearly two decades since high school. We visited, and as we caught up and reminisced, I began to realize that I could pinpoint the time when our lives had first begun to diverge. It started during those boy-crazy middle-school years, when we were at the cusp of growing up, when our futures had not yet been written.

Some of us—because our parents were strict or wealthier and more educated, or because we were “good girls” too nervous to break the rules, or because we were just plain lucky—got out. Others got pregnant.

When we were in sixth grade, one of Darci’s good friends, a 14-year-old, had a surprise baby. She’d been feeling sick, and her mom took her to the doctor, who said she was due in a month. A few days after that, the girl went into labor. I heard her parents—the shocked and befuddled grandparents of a little boy just a few days old—relay this story in Darci’s living room.

I knew that what had happened was both wrong and not unusual. Arkansas had, and continues to have, one of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the United States. Girls became pregnant in our middle and high schools, at least one a year. They dropped out or graduated as mothers and sometimes as wives, bearing a new name on their diploma.

In seventh grade, when we were 12 and 13, one of our friends had a pregnancy scare. She was dating a boy from another town who was at least 16. After a day spent sick and upset in the girls’ bathroom, she turned out not to be pregnant. But none of us thought to tell an adult, even though I knew of some who would have helped. We were not even quite teenagers but we were already navigating the full consequences of adult behavior alone.

In Clinton, sex—and the question of whether we were allowed to have it or talk about it—was related to how people viewed girls’ futures. The idea that we might become fully realized adults, experiencing sexual freedom and fulfillment, was not fathomable. We could become helpmeets for our future husbands, or we could be ruined.

The girls who got pregnant were stigmatized—until their babies were born. Then they were revered as mothers. Our school was full of young moms who were still students, and those newly graduated would come back for ball games and other events, babies on their hips. It was an endless churn, baby after baby, raised in families that spanned five or six generations because so few years separated grandmothers and mothers and daughters—and because the girls couldn’t take care of their newborns without help.

In response to the high rate of teen births, people turned to the church. In 1993 the Southern Baptists founded True Love Waits, an organization that promoted abstinence until marriage. My friends began to wear “promise rings” in middle school. Because some already had serious boyfriends, they dedicated their rings to them as sort of a pre-engagement promise.

Outside the church, the information we got was mostly misinformation. One day in seventh-grade health class, our teacher drew a big circle on the board, and a tiny dot within it. “This circle is the microscopic holes in a condom,” he said. “They’re microscopic, and that means they’re tiny. But guess what’s even tinier?” He pointed his chalk at the white dot on the board. “AIDS.”

The message at church was that we had to keep ourselves pure for our husbands, and the message at school was that sex would either kill us or leave us pregnant, and there was nothing we could do to prevent either scenario except abstain.

Despite the sermons, my friends were still having sex at about the same rates as teenagers elsewhere in the country. They were keenly aware that it was frowned on, and if a crisis resulted, they hesitated to seek help from an adult. In some cases, it kept them from breaking up with their boyfriend and made them vulnerable to exploitation and assault, though I didn’t know to use those words back then. As if they were living in the Victorian era, they assumed that because they’d gone all the way with someone, they would have to marry him.

My momma spent her life guarding me and my sisters against this fate, lecturing us, warning us, and making sure we came home on time each night. But when Darci started to go boy crazy, there was no one at home to stop her.

In her den—where we’d spent so many hours playing Twister and having sleepovers on the floor—she took to hanging out with her older brother and his friends. At 12, she started sneaking out at night, tagging along with them to house parties. When I interviewed her after we reconnected as adults, she remembered this time as a turning point in her life.

I sneaked out with Darci one night soon after my 13th birthday. I was sleeping over, but instead of going to sleep, we went into the bathroom and put on makeup. My lipstick was mocha-colored, and Darci’s was tinted orange. She fixed her hair so that it was wavy, gelled it to tame it, then tied it in a knot on top of her head. I put on a denim shirt and jeans.

First we picked up a friend of her brother’s whose parents were away. He was in his bedroom getting ready, and I kept giggling.

“Monica, you’re like, ‘Oh my God, I’m in a boy’s house,’” Darci said, laughing.

Then the three of us crossed the high-school campus and the football field to a ramshackle old A-frame well past its tear-down date. Half a dozen kids were already there, mostly high-school boys, drinking. More boys drifted in and out of the house, grabbing bottles of beer. It was my first party where people drank and smoked openly. I was nervous and bored, while Darci made everyone laugh effortlessly, and abandoned me on the porch while she went off with a guy to hook up.

But I can see, looking back, that she was a vulnerable child. Both of us kept diaries for years, and after I came back she let me read through hers. They were full of descriptions of the boys she liked. In one entry, she described sneaking out to meet a boy she had a crush on. Her crush was drunk. “It was actually kind of funny, but it didn’t seem so funny when he started getting on top of me,” she wrote. “But on the other hand he was so drunk that he wasn’t strong enough to stay there.”

Later, the same boy would see her riding around with another older boy and chase her in his car. He followed her to the house where she was spending the night, banged on the door, and tried to pull her outside. The casual violence of it shocked me when I read it as an adult.

At that first party, I saw a glimmer of this other life Darci had begun to live. When we got back to her den late that night, I told her that her new friends were sleazy. “That’s not very nice, and not very Christian” was her response. “I thought we were trying to see the good in people.”

Parties like that one were uncomfortable for me, largely because of my dad. Starting when I was as young as 4 or 5, I understood that he had a drinking problem. We lived in a trailer and he didn’t make much money. Momma, who had quit work to raise me and my sisters, was often frustrated and, I realize now, lonely.

Daddy came home for dinner one night talking funny and acting weird, and Momma was mad in a different way than usual, and sad. Daddy was apparently angry that supper was spaghetti, and yelled.

“Daddy, what’s wrong with you?” I asked, yelling too.

“You want to know what’s wrong with me, Monica? I’m drunk, that’s what’s wrong!”

When I was little, I thought that when people were drunk they were drunk forever. Later, I learned that this is not true. Even later, I learned that sometimes it is.

When it came to liquor, there were two modes in Clinton: alcoholism or abstinence. This paralleled the bifurcated morality I saw everywhere: girls were either virgins or whores; students were either geniuses or failures; you could go to church or you could be a sinner. The town seemed to operate in two modes—the buttoned-up propriety of the churchgoers, who held power in the county, versus the rowdy hillbillies in families like my dad’s. The rigid divide allowed no room for subtleties or missteps.

Even children were sorted into the binary: the upstanding citizens and the ne’er-do-wells. Darci was getting a reputation as the latter. At her 14th-birthday slumber party, half the girls sneaked out and half didn’t. After that, the “good” girls stopped going to Darci’s house.

I felt trapped by this system. I didn’t want to be judged by those around me, but I didn’t have the power to ignore their judgments. I never really fit in with either the “good” kids or the partiers, but I decided to align with the “good” kids. Today it’s sometimes painful, or laughable, to look back at how severe I was. I didn’t believe in the religious prohibitions on sex before marriage, but I did see the social consequences that those who failed to follow them in Clinton suffered.

Our friend Vanessa Allen, who was maybe the most boy crazy of us all, suffered the most. Vanessa had long, curly black hair and was the oldest of four kids. Her mom, Susie, had gotten married as a teenager and had Vanessa at 18. Vanessa wore a promise ring in middle school, but she liked attention from boys and had a reputation for being a flirt. I remember her wearing a tight-fitting bodysuit at a football game. When she walked past a group of grown men, they whistled at her, and one of them said admiringly, “Someone’s been eating her beans and cornbread!” She was 14.

Adults had taught us girls to keep boys from touching us before marriage, but no one ever told us what to do if we wanted to touch them. In that space between Vanessa’s desire and her shame, other girls smelled blood.

The first time Vanessa had sex, she asked her boyfriend to stop, and he didn’t. Later, with other boys, Vanessa sometimes felt like she couldn’t say no to their advances, because she’d already lost her virginity. Only many years later did Vanessa recognize some of these incidents as sexual assaults, she told me when I visited her in 2017. She didn’t blame the boys, necessarily; they were just doing what everyone expected them to do, she felt. But her reputation suffered.

At Christmastime during ninth grade, she wore a Santa shirt that said ho ho ho across the front, and one of our friends pointed at her and said, “Hey, that’s right! Ho, ho, ho.” Everyone laughed. Vanessa went to the office, sobbing, and called her mom for a new shirt.

The following summer, Vanessa and her parents went to Colorado to visit family. At the church, they met the preacher’s son, who Vanessa and Susie thought was about 19. He and Vanessa hit it off, and after she returned to Arkansas, they kept in touch. That fall, he traveled to Arkansas and stopped to visit. He asked Vanessa to marry him, and she said yes. She found out then that he was 24.

He was a good Christian, however, and she liked him. Sitting in her living room so many years later, she told me she knew that people in town called her a whore. They wouldn’t be able to do that if she moved to Colorado and became a wife.

Vanessa had to be married across the border in Missouri, because in 1996 not even Arkansas allowed 15-year-old girls to wed, not even with parental permission. Vanessa’s parents not only gave their permission, but her dad, a minister, performed the ceremony.

Susie later told me that allowing Vanessa to get married was the worst mistake she ever made. But she felt like she had to, that Vanessa had no future in Clinton. I asked similar questions of Darci’s mother, Virginia: Could she have set more boundaries, protected her better, in those years when her home became a teenage clubhouse, complete with alcohol and, eventually, drugs? No, Virginia said. She could never make Darci do anything she didn’t want to do. “Darci made her own choices,” she insisted. It troubled me that she so casually referred to teenage behavior as “choices,” when we had been only children, still learning and growing.

In 1994, the summer after we finished middle school, Darci broke my heart. We were out at Greers Ferry Lake with a few others on an August day so hot, we struggled to move fast or take full breaths. The warm green water was barely an escape. We walked a good distance out, kicking up slimy mud from the bottom, negotiating the minnows that nibbled at our feet, then swam out to the floating orange buoys that marked the edge of the swimming area.

The lake fills a part of the valley formerly known as the Big Bottoms, which had once comprised five fertile farming communities. Darci and I had read that when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the dam that made the lake, it hadn’t exhumed the bodies from the cemeteries but just let the lake fill in above them. We would plunge down as far as we could and then open our eyes, terrifying ourselves with thoughts of what we might see.

That day we sat along the line of buoys, dangling our legs in the water, chatting mostly with the person next to us. I was sitting next to our friend Erica when she casually dropped the news that Darci had lost her virginity to one of her brother’s 18-year-old friends. Darci was only 14.

I must have looked shocked. “Didn’t you know?” Erica asked.

I hadn’t known. Darci, I felt, had given up on our dream of getting out. It was the first real fracture in our friendship, and it would grow wider over the years, as I stayed focused on leaving Clinton and she became lost in it.

In January of our senior year, Darci had a miscarriage, something she shared with me only years later in an interview. At the time, she told no one about it. But she had a doctor’s note saying she needed to rest. She kept using Wite-Out to extend the date on it in order to get out of school. She did this so many times that she missed too many days to graduate. Her teachers and the principal, perhaps having already written her off as a lost cause, never bothered to warn her that there was a hard-and-fast rule and that she was about to break it. I was the class valedictorian; when I gave my speech, she wasn’t there.

Darci drifted, she used drugs—pot, a range of pills, occasionally crystal meth—and at 22, she became a mother for the first time. She got in legal trouble for embezzling from her employer, for which she was convicted in 2008; she was sentenced to probation and lost custody of her children, who moved in with their grandmother. In the years that followed our reconnection, she swung between periods of stability and destructiveness, bouncing in and out of contact; lately she’s been doing better.

It wasn’t just Darci. I returned home to find my whole town in a long, slow decline, on the verge of dying itself. Drug epidemics take root in places that are already sick, already suffering. Momma had been right, it seems, to focus on getting us out, guarding us from boys and early pregnancy and keeping us distant from the people she thought would trap us here. I asked a second cousin of mine about this once, the man who would become the father of Darci’s children. I told him that I wished I’d known his part of my family better, but that my parents had kept me from getting close. “There’s probably a good reason for that!” he said. “This town didn’t suck you down the way it did some of us.”

When I started to investigate why women like those I’d grown up with were dying younger, I thought I was looking for reasons: What was different about their lives, and why? I realize now that I was looking for one person: my friend Darci.

This article is adapted from the forthcoming The Forgotten Girls: A Memoir of Friendship and Lost Promise in Rural America.

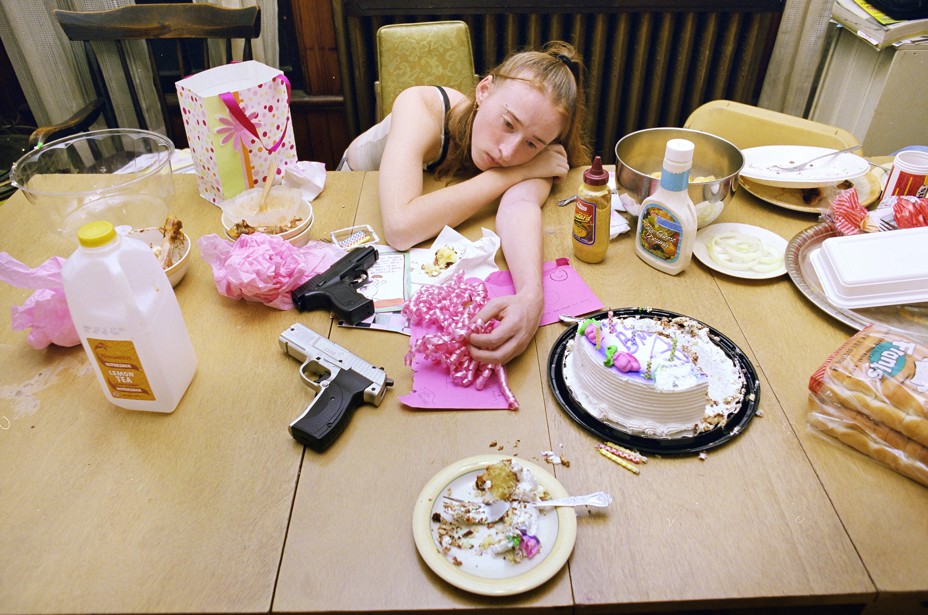

The images are from the book Upstate Girls: What Became of Collar City, published by Regan Arts 2018.