As an epic oil crash threatened more havoc on a pandemic-stricken global economy in April 2020, the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia and other G20 countries met to thrash out a solution. The co-operation helped end an Opec+ price war and restored stability to the market. Prices recovered.

Two-and-a-half years later, and nine months into Russia’s war in Ukraine, such collaboration on energy between global powers seems a distant memory.

Moscow has weaponised its natural gas supplies to Europe for months and is now actively trying to disable Ukraine’s electricity network. Consumer countries have become competitors as they race to secure scarce energy supplies. Fractures are visible in the decades-old Saudi-US oil relationship. Even in clean energy, leaders such as Joe Biden talk of a new battle to dominate supply chains.

The potential unraveling of the old order in the global oil market will reach a defining moment over the next week when Europe starts to block Russian seaborne crude from the continent — one of the strongest responses yet to Vladimir Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine.

The new sanctions will also stop European companies from insuring vessels carrying Russian oil to third countries — unless those countries accept a price for the oil dictated by western powers. In other words, western countries will attempt to impose a cap on the price of oil sold by Russia.

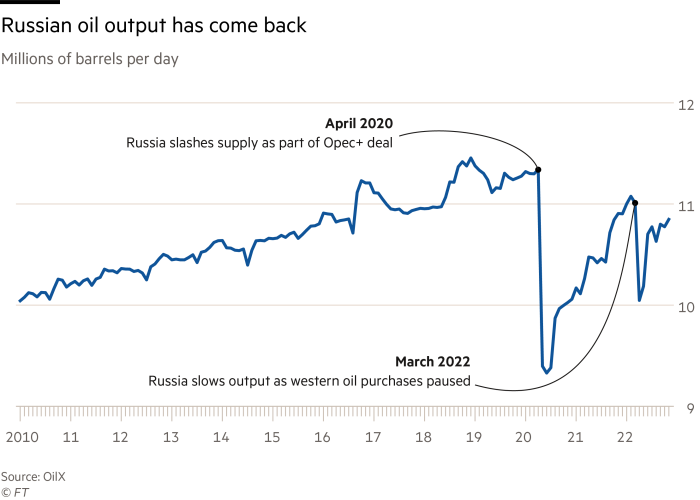

No one can say how disruptive these measures will be. Sanctions imposed on Russia since Putin ordered troops across Ukraine’s border on February 24 have barely dented the country’s oil exports or the Kremlin’s oil income.

But the very principle that Moscow’s geopolitical foes will set the price at which Russia sells its crude is a humiliation for a petrostate that produces more than 10 per cent of the world’s oil and sits alongside Saudi Arabia at the top of the Opec+ cartel. A price-setter would become the ultimate price-taker.

Alexander Novak, Russia’s deputy prime minister, will have a chance to discuss Moscow’s response when he sits down with Saudi energy minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, at another Opec+ meeting in Vienna on Sunday, a day before the European embargo and price cap plan come into effect.

For energy industry veterans, the coming days mark a moment of deep peril for the oil market — and a global economy that still depends heavily on the commodity. Established geopolitical norms have been eroded in the past year, they say, and supply chains that have existed for decades are now being upended.

Russia’s willingness to torch its gas customer base in Europe and Saudi Arabia’s decision last month to slash oil supply — despite fierce opposition from the White House, who accused its Middle Eastern ally of aligning with Moscow — were just two examples. But consumer countries have acted too, from the US’s willingness to drain its emergency oil stockpile to drive down petrol prices, to western attempts to purge Russian energy from their economies.

“These are tectonic shifts. Global markets were built on these trunk lines, of [natural gas] supply going between Russia and Europe, and both oil and gas between the Middle East and Asia,” says Roger Diwan, a veteran oil analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights in Washington.

“We don’t know how this market is going to function after a certain date. The adjustment will be dramatic . . . it’s going to be confrontational and it’s going to be volatile.”

The politics of the cap

If a historic breach in the global energy order is indeed imminent, there have been few apparent signs of this in the crude market. Brent, the international benchmark, has fallen from $120 a barrel in June to $85 today as traders zero in on signs of recession.

China’s commitment to a “zero-Covid” policy has also crimped demand and provided a release valve of sorts for wider pressures in the market.

But clear strains in energy markets remain. Crude prices remain higher than at any point between 2015 and 2021, while diesel — which Russia exports a lot of — is still extremely elevated.

European natural gas prices may have fallen from peaks close to $500 a barrel equivalent this summer, after Russia moved to almost completely sever supplies. But gas is still trading at about five times the historical norm, wreaking havoc on economies and stoking inflation globally.

If China were to ease Covid restrictions next year, its demand for oil and imported liquefied natural gas, which Europe is now heavily reliant on, could soar.

“We’re clearly still in a very precarious market,” says Doug King, chief executive of RCMA Capital, which runs the Merchant Commodity Fund.

“The relationships between the great powers of the oil industry has become very fragmented. Everyone in the industry is feeling a bit battered as oil has been hit from all angles this year. ”

The White House has worked for months to hold back prices, releasing unprecedented volumes of oil from its own emergency stockpile, while maintaining constant — if so far fruitless — pressure on Saudi Arabia and other producers to keep increasing supply.

The price cap idea, first promoted by the US Treasury department, is the most important and controversial initiative. For the Biden administration, it is a method to curb the Kremlin’s revenue while preserving the flow of Russian oil to the market in order to keep more oil price inflation at bay.

The plan is actually partly designed to offset much tougher restrictions put in place under EU sanctions on Russia.

Given that the EU and UK dominate the insurance market for oil tankers, the US feared the European sanctions would lead to a collapse of Russian supply as vessels avoided its cargo. Under the price cap plan, vessels would be allowed to access European and UK insurance provided the Russian oil they carry was bought at the price set in western capitals.

The G7 endorsed the Treasury’s plan and the EU incorporated it into a new set of sanctions announced in October after Russia illegally annexed more Ukrainian territory. But these sanctions included yet another onerous clause, widening the ban on shipping insurance to any vessel that had ever carried “uncapped” Russian oil. The US lobbied the EU to water down this provision too, say people familiar with the effort.

“Extending the insurance and services ban to all oil tankers — both EU and non-EU — carrying uncapped Russian oil dismayed US officials, as it would have caused a much bigger supply disruption,” says Bob McNally, a former adviser to US President George W Bush and head of Rapidan Energy Group. People familiar with the discussions now expect the EU to impose a limit on the duration of any ban.

“Walking the Europeans back from an indefinite vessel ban chewed up a lot of time but was worth it from Washington’s perspective, because it threatened to make a bad problem much worse,” says McNally.

The actual price of the cap is still a matter of debate. Some European countries want a truly punitive price near $20 a barrel, while others call for a range of about $60 or $65, say people familiar with the discussions. The latter price is similar to what Russia is already receiving for its oil.

“With the current pricing being discussed, this seems to be much more of an inflation reduction effort than a Russian revenue reduction one,” says Helima Croft, head of global commodity strategy at RBC Capital Markets.

Could prices rise?

How will the market react to the attempts by politicians to rig supply and price?

While there have been few signs of a price spike, some analysts believe the market has become complacent about the potential supply risks stemming from the new EU sanctions and price cap.

“Confusion around the price cap has left the market thinking the EU can buy Russian oil,” says Amrita Sen, head of research at consultancy Energy Aspects. “This is entirely mistaken, as the embargo supersedes the price cap.” Oil markets could tighten “significantly” in the spring, Sen says.

Some traders point to earlier dire warnings of shortages, which never materialised, such as concerns in 2019 that rules on shipping fuels due to come into force at the start of 2020 would disrupt diesel supplies.

Last spring, the International Energy Agency said sanctions on Russia’s oil could see its production plunge by almost a third within months — an alarming prediction that helped push up global prices and contributed to a decision by western nations to release emergency oil stocks.

Wary of believing the latest predictions, traders may be left exposed, argues Martijn Rats, chief commodity strategist at Morgan Stanley.

“Russia has managed to export [its oil] pretty much at a constant rate,” Rats says. “If it [the embargo] turns out to have teeth, and a lot of oil needs to be rerouted — and some will be lost in the process — then it will be positive for oil prices.”

Others argue that the price cap itself could trigger price increases. The frictions now being built into Russia’s oil trade will be immense, with “significant impact” on oil markets next year, say analysts at Bernstein.

About 2.4mn barrels a day of Russian oil will need to find a new home outside EU and G7 countries. India, China and other buyers are expected to take up some of this slack. But they have indicated they will not participate in the price cap scheme, wary of threatening relations with Moscow or being seen to bow to the west.

Bernstein estimates Russia could require as many as 100 additional vessels willing to operate without western insurance to keep its oil flowing outside the cap. This is a level they think Russia will struggle to secure even if it can tap the so-called “dark fleet” of tankers used by sanctioned countries such as Iran. As a result, they think supply will fall, pushing prices to $120 a barrel next year, even with a recession.

Vitol, the world’s largest independent oil trader, estimates Russian exports could drop by as much as a 1mn b/d, around 20 per cent of the volume it ships by sea.

The impact could be even more dramatic. The Kremlin has already said it will withhold supplies to countries co-operating with the price cap. The US Treasury argues Moscow will not go further and will still seek to sell its oil to other countries as curtailing production would risk long-term damage to its oilfields.

“We have no reason to expect that they would do that,” says a senior Treasury official. “Because ultimately, it’s not in their interest. Any action they take to drive up prices would have an impact on their new customers.”

But recent history has made others less sanguine. Long-term economic self-interest hardly motivated Moscow as it demolished its reputation as a reliable natural gas supplier to Europe, they argue.

“They said they would shut off gas supplies to anyone who doesn’t pay in roubles — and that happened,” says Rats. “You have to take into account the possibility that [cuts to oil exports] might actually happen.”

Others in the industry also point to Russia’s capacity to make trouble elsewhere. The 1mn b/d pipeline carrying Kazakh oil through Russia to the Black Sea, already shut by Moscow briefly in recent months for unusual weather reasons, could be a target. Russian proxy forces maintain a presence in Libya’s volatile oil sector too.

“I think the Russians likely have every intention to make this winter as miserable as possible for the west to make us reconsider our support for Ukraine,” says Croft at RBC. “We have made it very clear our pain point is energy, so I think Putin will seek to make this energy detox debilitating through a range of his hybrid techniques.”

It leaves much to be discussed as Moscow officials join other Opec+ members in Vienna on Sunday. The meeting will be only two months after their supply cut caused such anger in the US — and just hours before western countries make their own audacious attempt to try to reassert control of prices.

The Opec Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE insist they are not siding with Russia and merely attempting to manage a turbulent market that remains the lifeblood of the global economy. But privately they chafe against the price cap believing it could one day be turned against them.

They also point to what they see as the hypocrisy of the west: demanding higher production while also seeking lower prices, which the industry argues has stymied investment and left the market ill-prepared for this crisis and what might come next.

The desire of western countries to accelerate the shift away from oil and gas is also a long-burning fuse under the relationship, posing an existential threat to the power of Opec’s leaders even if their citizens are among those most exposed to climate change.

Suhail al-Mazrouei, UAE energy minister, poked at some of the west’s apparent contradictions on energy policy after the last Opec+ meeting, arguing that their efforts to boost prices should be welcomed in western capitals.

“It’s about what’s good for the market and ensuring we have enough resources for you guys [in the west] in the future,” he told the Financial Times.

Sunday’s Opec+ meeting could be another milestone as a global energy order based on decades of deepening connections between producers and consumers unravels in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“They openly used their energy, their gas, as a weapon — and it basically told the EU that it could use energy as a weapon against them,” says Diwan of S&P. Now comes the undoing of an established order.

“It’s the price cap. It’s the sanctions. It’s Russia’s action on gas markets. It’s Opec’s reaction to it. It’s Saudi Arabia’s policy . . . The potential dislocation in the near term is not controlled.”