We've heard some strange stories in our time, but this one sounds like a tale so long it must surely be made up. Only it's not. Back in 1982, the Musicians Union in the UK, while claiming to be working in the interests of its members, tried to ban the synthesizer and other tech music gear.

That's right: a union working for musicians banned a musical instrument. Well, things were a lot different back then…

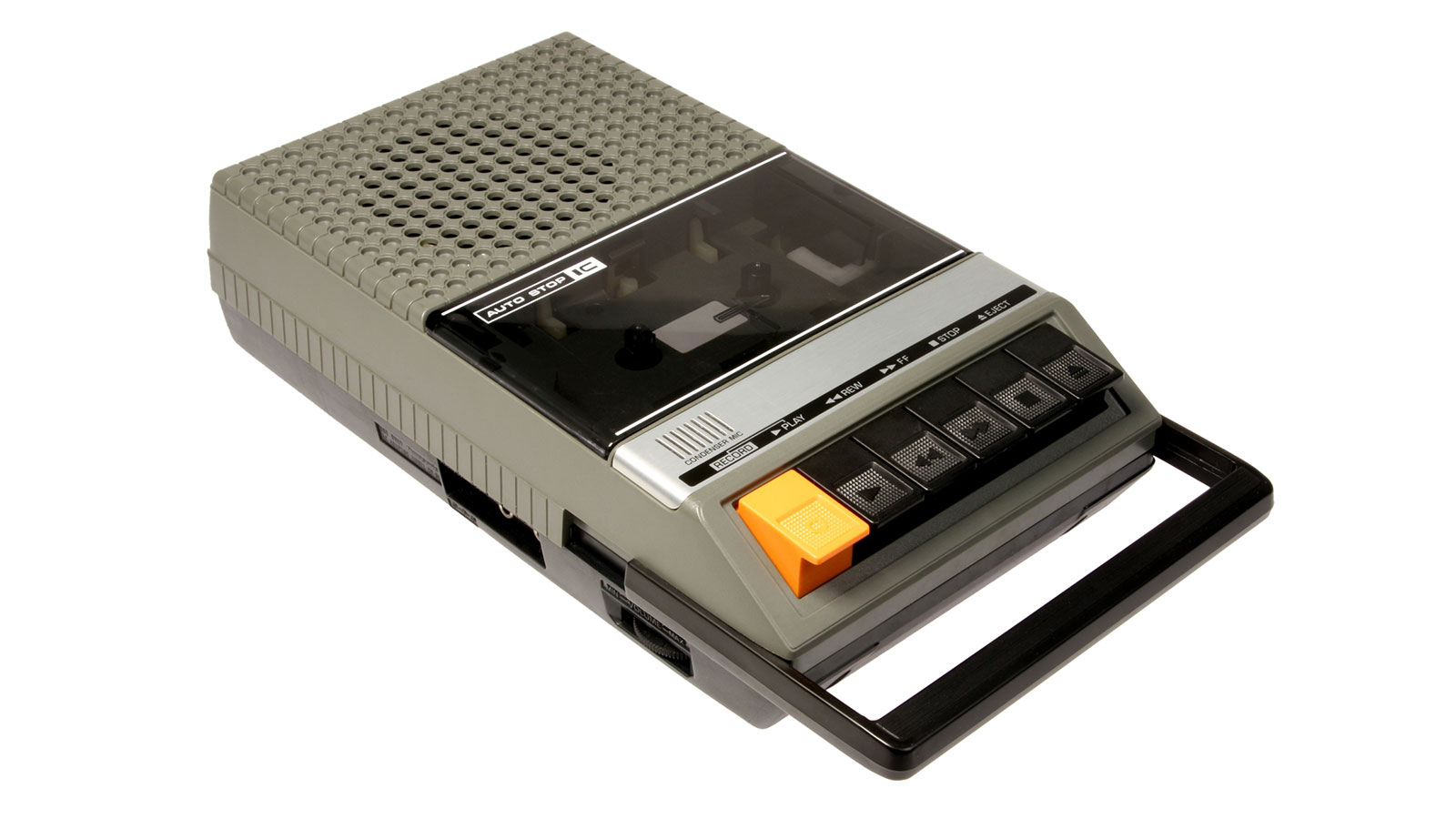

In the early 1980s in the UK, the Musician's Union was often in the headlines. In 1981, for example, this most vocal of unions, along with the British Phonographic Industry and Music Publishers’ Association, took an advert out in The Guardian and The Times claiming that “Home Taping is Wiping Out Music”.

If anything, home taping was spreading the word and promoting music.

These ads were meant to wage war on evil pirates who were using cassettes to record vinyl records, threatening the livelihoods of the music business (which, from memory, seemed to be doing very well for itself at the time).

The problem was that the vast majority of the home taping was done by people like us who were recording vinyl we'd already bought, or making compilation tapes – remember those – for mates who, more often than not, would go onto buy the albums. If anything, home taping was spreading the word and promoting music.

The campaign was, then, essentially a waste of time, and greeted with dismay. Indeed, we also recall another ad aimed at evil home recordists titled 'Home Taping is Killing Music', presumably put out by the same team. But then some clever wag changed it to 'Home Taping is Skill in music'. That was the kids sticking one to the grownups in the '80s.

Some clever wag changed it to 'Home Taping is Skill in music'. That was the kids sticking one to the grownups in the 80s.

But in 1982, the MU went even further, again apparently in the interests of its members. The union decided to try and ban synthesizers and drum machines, which it feared were literally taking food out of the mouths of real players.

So how did this ridiculous state of affairs come about? Believe it or not - and we really do believe this - it was all down to crooner extraordinaire Barry Manilow.

Manilow had replaced several orchestral players with synthesisers for a tour – putting synth players in work while taking string players out of work. The MU was furious.

Maybe the union even wanted to make it an offence to own a synth, driving the likes of Howard Jones, The Human League and Gary Numan into a seedy criminal underworld.

On the 23rd May 1982, Bob Moog’s birthday no less, the organisation passed a motion for an outright ban on synthesisers. In his excellent book, From Club Culture to Style Culture, the Story of the New Romantics, author Dylan Jones summed up what happened.

“By 1982, the synth had become so pervasive. When Barry Manilow toured the UK in January, he used synths to simulate the orchestral sounds of a big band, after which the union passed a motion to ban the use of synths, drum machines and any electronic devices ‘capable of recreating the sounds of conventional musical instruments’.

"They were particularly concerned about the possible effect on West End theatrical productions, imagining orchestra pits full of ‘technicians’ instead of musicians.”

According to MUHistory.com it was never actual MU policy, but an 'executive committee' did pass a resolution to ban synths later that year.

We're not quite sure how the committee intended to police the ban; whether it would merely ban synth players from being in the union or even try and ban the actual selling of synths.

Maybe the union even wanted to make it an offence to own a synth, driving the likes of Howard Jones, The Human League and Gary Numan into a seedy criminal underworld, only able to play in secret speak-easy venues, with audiences only discovering the gigs through whispered conversations with an underground network of Korg, Yamaha and Roland 'dealers'.

OK, we have overactive imaginations – but that would make a great film, wouldn't it?

Whatever they meant it to be, that ban actually being passed now seems like one of the most ridiculous acts in the history of music and technology. While that's easy to say in hindsight, it also riled actual synth players a lot at the time – many of whom were MU members – and they decided to set up an organisation called the Union of Sound Synthesists.

We're not even sure that many orchestra players agreed with the ban, mostly because orchestra players tend to have very good hearing.

To be fair to the MU – and we're trying to be balanced here – we can see why synths that were trying so hard to imitate 'real' sounds (brass strings and so on) in the early '80s might annoy a musician's body fearing for the livelihood of its members.

But the NME called the MU 'Loonies', and we're not even sure that many orchestra players would have agreed with the ban, mostly because orchestra players tend to have very good hearing.

While the synths in question were trying to copy real instruments, they were absolutely rubbish at it – and orchestra players could probably spot that. Synths were much better at making their own sounds, which thankfully they did, for tracks like this classic from the year in question.

Nor was this the first time the MU had been involved in trying to ban something. The union had tried to stop the use of the Mellotron in the 1960s because of its string playing abilities. And, according to The Guardian the MU even once tried to insist that bands appearing on UK TV show Top Of The Pops would record their backing tracks the afternoon before appearing on the show – to provide proof they could actually play it!

Amazingly, the synth ban apparently stayed in place, although it was hardly enforced. We certainly can't find any reports of synthesizers actually being banned, nor Rick Wakeman and Nick Rhodes being given lengthy prison terms for owning them. Although, again, either of these scenarios would make for a great TV show.

Thankfully, the MU has become a much more welcoming and sensible organisation. In 1997, the body relaxed its anti-technology stance somewhat when it allowed DJs to join – we'll leave you with your own thoughts on that one. In the same year, the pretty ineffectual ban on synthesizers was lifted.

Luckily, the MU seemed to have missed the rise of the computer in music making otherwise that would have been for the chopping block too.

The irony is that this was pretty much the same year that software instruments first started being developed commercially. And if you look at how much they have advanced – orchestral libraries these days are amazing – they could have been seen as more of a threat to musicians than the synthesizer ever was.

Luckily, the MU seemed to miss the rise of the computer in music making - otherwise that could have been for the chopping block, too.

Since the MU's spat with technology, there have been several other run -ns between musicians and studio tech. In 2013, the Guardian ran a story about two high profile film composers complaining that 'synthesized orchestras' were taking over.

Carl Davis (who scored the World at War documentary series) apparently said that synthesised soundtracks lacked "the heart" of symphonic music. He'd clearly not seen Blade Runner, some three decades before.

Christopher Gunning (who wrote the Bafta-winning score for La Vie en Rose) was also quoted in the piece as saying, "A lot of television music has got to the stage where I have to turn it off. I find the music so blooming irritating. Part of that is, I am afraid, the poor quality of the musical composition."

Carl Davis said that synthesised soundtracks lacked "the heart" of symphonic music. He'd clearly not seen Blade Runner.

Ten years on from that, we're at the stage where software is perfectly able to recreate a lot of orchestral content, so where is the MU now? The truth is that hiring a 70-odd piece orchestra was always a costly exercise and only the biggest budget films and TV shows have ever had the cash to do that, whether that was in the 1980s or now.

Orchestras are also hired – somewhat ironically – to produce the very orchestral libraries that are currently big business in the music technology world. We witnessed one such orchestra recording at Teldex Studios in Berlin for an Orchestral Tools library a few years back, and not one member of that orchestra was complaining about technology putting them out of work.

Of course, you could argue that the MU was right: technology has gone on to replace real musicians in certain areas of the music business. But another way of looking at it is that technology has increase the actual size of that business.

It has levelled the playing field so much that many more people can get involved and actually make music – it's not now just about those who can move a bow in the right way and at the right time; instead, all of us can have a go.

Music making is not now just about those who can move a bow in the right way and at the right time.

And on the other side of the playing dice, there will always be an audience eager to watch an 80-piece orchestra in full flow, and films with big enough budgets to record them.

Looking back, then, that MU decision seems – to put it politely – a little rash. But whatever you think, please don't tell any Musician's Union that we're just on the brink of another technological explosion in music production. You can just see the NME headlines now: "Loony Tunes! MU bans AI".

The UK Musician's Union is thankfully now a much more welcoming organisation with lots of benefits for musicians and gear of all shapes, sizes and electrical persuasions. You can find out more about the excellent work they do at the organisation's website.