Some bands carve their names into history. Others go down as cautionary tales. The Stone Roses, who released their landmark debut album 30 years ago this week, did both.

The story of the Roses and of that self-titled record – a dreamy, liminal indie classic that is somehow not as adored as it should be – is one of naivety, ambition, and tragicomedy. It is spattered with hubris, genius and literal paint.

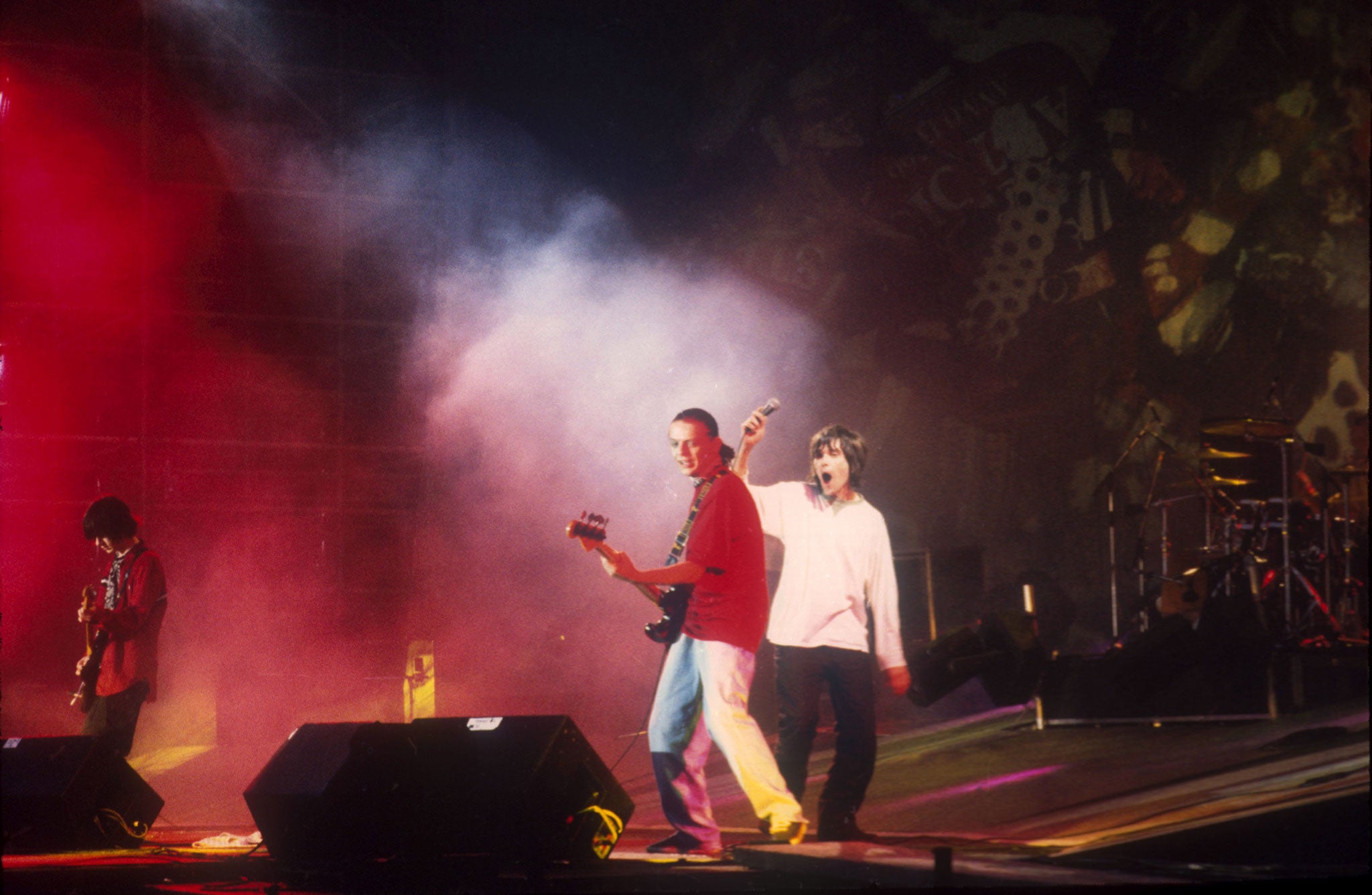

Yet looking back, what’s remarkable is how these four wide-trousered Mancunians could be both unapologetically ambitious and nakedly transgressive. No band today would dare to combine pop and politics as they did (“Hats off to Gerry Adams,” was the first thing they said when playing a comeback concert in Cork in 1995), and the songs – “I Wanna Be Adored”, “Waterfall”, “I Am the Resurrection” – detonated like psychedelic firebombs. That swagger, cocksure with bells on, would become the default for British rock through the Nineties.

Thus – and this would likely have appalled these anti-monarchist awkward outsiders – they helped invent Britpop, too. The blueprint they created of the likely lad as misty-eyed romantic was followed by Oasis and, then, a zillion terrible Oasis clones. We have many reasons to be grateful to the Roses – but a few things to blame them for, too.

Ian Brown, John Squire, Gary “Mani” Mounfield and Alan John “Reni” Wren didn’t simply wear their hearts on their sleeves. They smeared their feelings all over their record covers. That was especially true of The Stone Roses. Arranged on the cover are three lemons and horizontal brush strokes: red, white and blue.

The colours reference the French flag and the anti-royalist philosophy of the First Republic. The lemons came from an anecdote Brown was told by an old Parisian revolutionary he’d met back-packing around Europe. Tear-gas raining down from above, the anarchist revealed, was his sharpest memory of the 1968 street protests. The best way of counteracting the sting, he explained, was to suck a lemon. From his pocket, he produced just such an item. The revolution could begin at any time and place. So he made sure always to have one at hand.

Brown took it all in, and years later made sure this upstart spirit was reflected in the cover of his band’s first LP. The finished artwork was by the group’s guitarist Squire. Influenced by mid-20th century abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, the record sleeve was a cheeky piece of appropriation and decontextualisation that was also original and subversive.

The same could be said of the music within. The Roses had patented an expansive psychedelic pop. Their sound looked back to the Sixties yet existed in its own self-imagined space between bedsit indie and, in spirit if not texture, the acid house movement poised to sweep Britain.

What made it all work were the personalities of the four musicians; a Beatles-esque spatter of contradictions that drove the band to great heights and also, when rancour later set it and it all tumbled apart, set them up as a cautionary fable of British pop.

The Stone Roses was initially a modest seller, slow to receive media attention. Yet, as a new decade dawned, a switch flicked. All of a sudden, the Roses were not merely a band, but a phenomenon that was reshaping youth culture in its image.

One curious London journalist travelling north to Manchester to interview the quartet was brought by Brown to his favourite clothing store. Here, he explained, he would source the “baggy” leg-wear that was becoming, along with Reni’s bucket fisherman hats, a signature of the group.

Surveying the racks of trousers, Brown explained that when he’d started coming to the establishment. they had stocked at most two or three pairs of flares. Now, the upstairs of the premises was wall to wall with them – caught up in a trend the Roses had helped popularise.

Brown and Squire were the yin and the yang of the group. Lower-middle class kids from Timperley in south Manchester, they grew up on the same street and met at the age of four.

They would steadily orbit one another in the decades that followed – never quite fast friends, much less kindred spirits. Rather, they were often wildly incompatible individuals who couldn’t quite get out of the gravitation pull of the other.

They’d played together on and off from their early 20s, their passion stoked by ‘you had to be there’ attendances of gigs by Joy Division and The Clash. Friends recall Brown as the natural born charmer, always jabbering, never sitting still.

Squire was somewhat of a prodigy – a visual artist as well as a guitarist and songwriter – but hard work too. He had an inner circle of precisely zero. Even those ostensibly close to him, such as Brown, often felt they were being kept at arm’s length.

He also was clearly hugely talented. Squire excelled at art, working briefly at Cosgrove Hall, the animation house known for Danger Mouse and stop-motion classics such as The Wind in the Willows. There was something painterly about his guitar playing too, which seemed to fill the mind’s eye with swirls and shimmers.

The Roses formed in 1983 and initially consisted of Brown, who’d spent the previous several years immersed in Manchester’s scooter subculture, guitarist Andy Couzens, bassist Pete Garner and drummer Simon Wolstencroft. It was at Brown’s suggestion they recruit Squire. Just a few months in, Wolstencroft left to play with Terry Hall’s The Colourfield and later The Fall, opening the door for Alan “Reni” Wren to join in 1984.

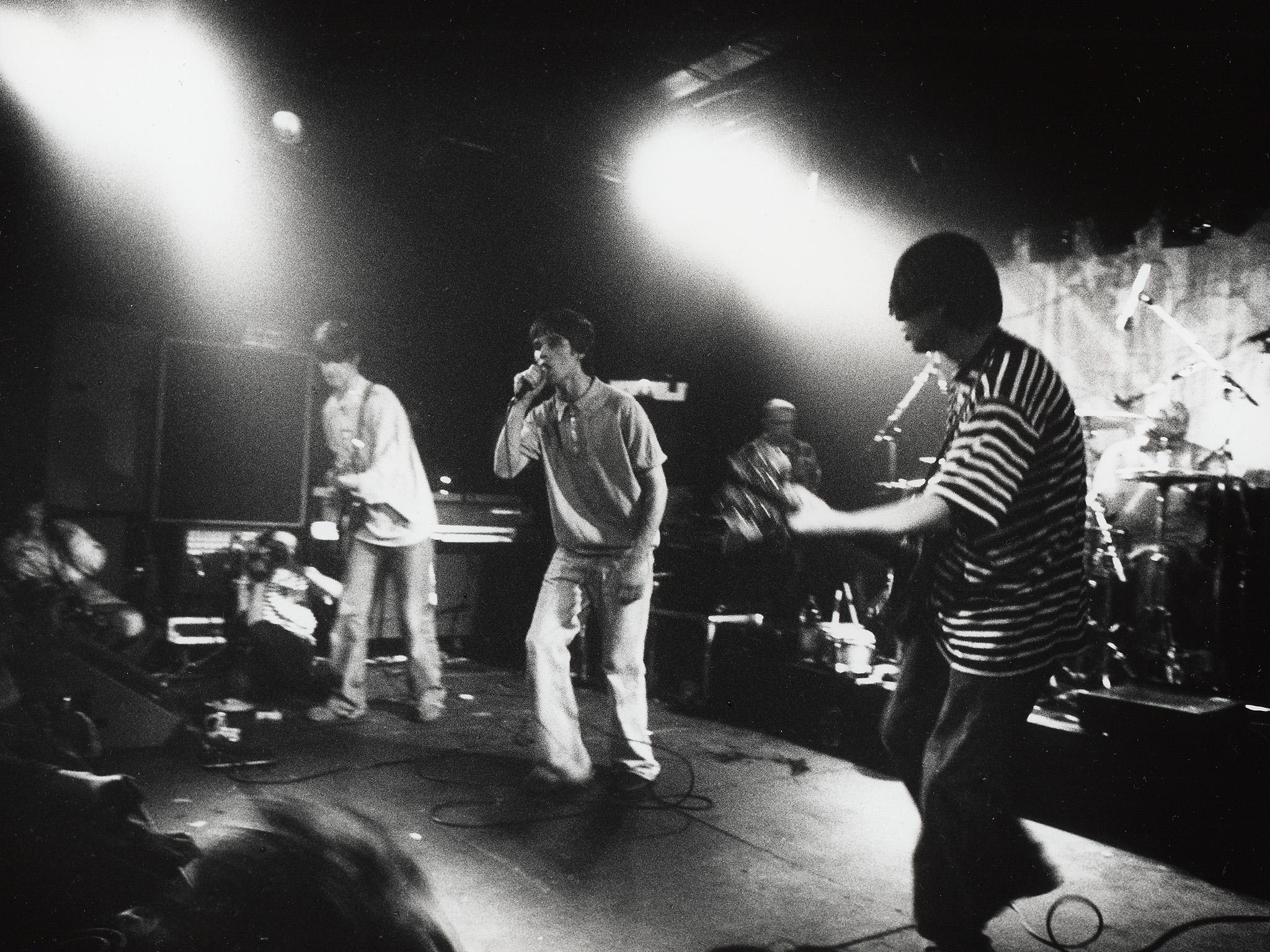

They had soon built a following in Manchester and the surrounding towns, but were nowhere near the force they would become. It was with recruitment in November 1987 of new bass player Gary “Mani” Mounfield, who had been in rival band The Waterfront, that something seemed to change. Brown, Squire and drummer Reni were dreamers. Mani was a rocker. Now the tweeness that characterised early singles such as “Sally Cinnamon” evolved into something slicker, sleeker, groovier.

Yet the Roses, less lightning in a bottle than nitro-glycerine in a flask, were never an entirely stable entity. Early on, Reni was regarded within the ranks as the natural talent. Indeed, Squire and Brown feared constantly that he would be head-hunted by a more established band (one particular obsession was that Mick Hucknall would pinch him for Simply Red).

Anxiety was thus infused into their DNA, along with that teary upstart spirit. Before Mani had joined, eager to expand beyond their loyal but modest fanbase, Brown and Reni had gone on a graffiti rampage, spray-painting the band’s name on walls in the suburb of West Didsbury.

It didn’t quite work. If anything, it turned potential fans against them. More successful, it initially seemed, was their hunt for a manager to take them to the next level. They believed they had found their man in local venue owner Gareth Evans.

Evans was larger than life and had auditioned for the group by dropping his trousers and attempting to sell them his underpants (his way of proving he could fast talk anyone in any situation). The real attraction, though, was his International 1 space on Anson Road. A far cry from the cramped practice rooms around Manchester, it was a place for the group to expand their sound unobstructed by low ceilings or walls looming too close.

Expansiveness soon became a watchword. Peter Hook, of local luminaries New Order, produced their October 1988 single “Elephant Stone”, an astral onslaught that found their songwriting reaching a new level. At that point, they were already signed to the little-known Zomba Music Group, via its Silvertone imprint.

The deal was agreed by Evans, apparently without consulting the band. One clause decreed that the Roses would not see a penny of royalties from their first 30,000 records sold. The contract, restrictive even by the standards of the time, would eventually come close to tearing the group apart and, amid lawsuits and counter-lawsuits, destroy their relationship with Evans.

But that was all in the future, long after The Stone Roses had made them stars. Besides, if their business sense was flaky, in the studio they were clear-eyed and determined. John Leckie, who produced their debut album, found them serious and very specific in their demands.

“They weren’t frightened,” he told NME. “They didn’t seem to feel any pressure other than that they were a band making their first album, and didn’t want to lose the opportunity to make it good. So there wasn’t any pressure to prove themselves – they knew they were good.”

Squire was the genius. But Brown was essential to Roses’ chemistry. He has since expressed annoyance with criticism of his reedy singing style. And while it is true that he was asked to attend vocal lessons early in the band’s history, those floaty declamations, especially on record, were the magic sprinkled atop Squire’s chiming chords.

His lyrics, too, set the band apart. Where their contemporaries were stuck trying to emulate Morrissey, Brown wasn’t afraid to be political. “Bye Bye Badman” was inspired by that same French revolutionary who inspired the album artwork. “Choke me, smoke the air / In this citrus-sucking sunshine I don’t / Care you’re not all there.”

“Elizabeth My Dear”, meanwhile, reapplied the melody of Scarborough Fair to a lulling anti-monarchist screed in which the narrator appeared to fantasise about shooting the Queen. “I’ll not rest / Till she’s lost her throne,” sings Brown. “My aim is true / My message is clear / It’s curtains for you …”

“I saw it on Clive James last Saturday,” Brown told an interviewer. “They were talking about how the British will never have another revolution because, at the end of the day, who’s going to be the man that puts a blanket of the Queen Mother’s head? I’d do it!” Can you imagine a band voicing such sentiments today? They’d be run off the internet.

The Roses toiled for seven months on their debut. But they were not aware that the songs they were making would define them for the rest of their lives. For one thing, they were too skint to ponder their legacy (Mani had to borrow £10 from Leckie for a taxi so that he could make it to the session on time).

And alongside the music, there were other things to worry about. With their reputation growing, the Roses were perturbed to discover that one of their earlier labels had reissued the wispy “Sally Cinnamon”, with a video made without their permission. In January 1990, they showed up unannounced at Revolver’s offices in Wolverhampton, and splashed paint over label owner Paul Birch, his wife and several parked cars (receiving a courts summons for their troubles).

By this point, The Stone Roses had been on the shelves for nearly six months, and the band were getting bigger and bigger. Their refusal to compromise became a talking point. They turned down a Rolling Stones support slot, and declined to play on Terry Wogan unless they could be interviewed too (apparently their plan was to remove Wogan’s rumoured wig).

Still, it was a glorious time. A period of innocence before their fall. Later, the Roses would be locked in endless wrangles with Zomba and Evans over their lop-sided contract. And they would become bogged down in the sessions for their lugubrious 1995 second record (the apocryphal difficult second album myth made flesh). Even their initially well-regarded 2011 return eventually petered out, leaving us only with two underwhelming, aura-destroying comeback singles.

But as 1989 ambled into 1990, how bright their future must have felt. Manchester, too, was basking in a moment. The Hacienda club was ground zero for acid house. Happy Mondays, James, The Charlatans were taking up the baton. John Squire’s shaggy non-haircut was trending, baggy pants were ubiquitous. We all seemed to live in the Roses’ world and it was magnificent.

As the best bands often are, the Roses in their pomp represented a thrilling jumble of contradictions. They were determined to do things their own way. But they also wanted to be successful. When, for instance, they found out James were headlining a charity concert at the International 1 at which they’d agreed to perform, they ran up their own posters with their names at the top of the bill. Then they went on late, and played so long James’s time was cut.

In the audience was a 16 year-old Liam Gallagher. His older brother, Noel, was an early fan, too. He saw in the Roses a foreshadowing of what he himself might become one day.

Thus in Ian Brown’s strut, and Jon Squire’s horizon-hugging guitars, were set the foundations of Britpop.

“We were into The Jam and The Smiths before that,” Noel Gallagher would recall. “We thought you had to go to college or be an art student to be in a band. When I went to see the Roses, they looked exactly the same as we did … When I heard ‘Sally Cinnamon’ for the first time, I knew what my destiny was.”