As we enter the final week of the election campaign with its scrappy debates and breathlessly seized “gotcha” moments, the impact of Gough Whitlam’s electoral reforms can be seen at every stage.

From votes for 18-year-olds, senate representation in the ACT and Northern Territory, equal electorates and “one vote one value”, Whitlam’s commitment to full franchise and electoral equity remain central to our electoral process.

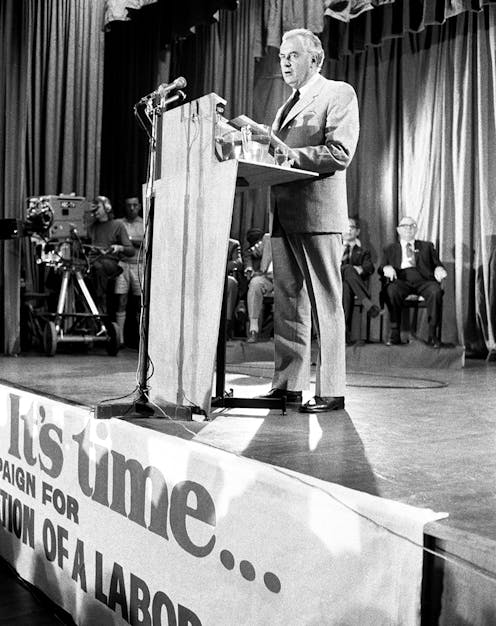

No less significant is the innovative and dynamic election campaign built around the central theme “It’s Time” which propelled him into office.

“It’s Time” was the perfect two-word slogan, encapsulating the urge for long overdue change after 23 years of coalition government, and carrying that momentum into the election itself.

This was Australia’s first television-friendly, focus-group driven, thoroughly modern campaign. Its impact on political campaigning in this country was profound.

Behind the glitz of the theme song and the over 200 policies enunciated in the policy speech, a raft of celebrities and leading figures from the arts – authors, artists, actors, musicians – played a major role.

Not just political star power

The presence of well-known identities at the launch in Blacktown Civic Centre lent an air of celebration – of celebrity and even glamour – to the dour set pieces that owed more to the old-fashioned stump speeches of decades earlier, still used by the outgoing Prime Minister Billy McMahon.

Led by soul singer Alison MacCallum, household names like singers and musicians Patricia Amphlett “Little Pattie”, Col Joye, Bobby Limb, Jimmy Hannan, actors Lynette Curran from the popular ABC series Bellbird, Terry Norris and Chuck Faulkner generated an immense reach for It’s Time both as a song and as a political moment.

Patricia Amphlett recalls:

The ‘It’s Time’ commercial was far more effective than anyone could have imagined. Long before Live Aid, it came as a shock to some people that popular personalities would stand up publicly and be counted for a cause.

They were not simply there for added political star power. They were there because the arts had been neglected and constrained by decades of unimaginative conservative government – and they shared a mood for change.

‘Intellectual and creative vigour’

Whitlam harnessed the deep sense of frustration of the arts community after years of “stifling conservatism” in arts policy settings. Direct political intervention in literary grants also had a stultifying effect on cultural production.

The author Frank Hardy’s successful application for a Commonwealth Literary Fund fellowship in 1968 had been vetoed by the Gorton coalition government because Hardy was a member of the Communist Party.

Whitlam was a member of the committee that had awarded Hardy the fellowship and it drove his determination to ensure arts bodies operated as autonomous decision-makers.

He brought arts policy to the fore both in the development of his reform agenda and during the election campaign.

He drew a direct link between a healthy cultural sector, national identity and a flourishing political sphere:

the relation between politics and culture is clear and real. Political vigour has invariably produced intellectual and creative vigour.

‘Refresh, reinvigorate and liberate’

The rapid elevation of cultural policy as a major area for change soon after Whitlam came to office on December 5 1972 gave voice to his pre-election commitment to the arts community “to refresh, reinvigorate and liberate Australian intellectual and cultural life”.

Just six days later, in the ninth of the 40 decisions made by the first Whitlam “duumvirate” ministry, the government announced major increases in grants for the arts in every state and the ACT and forecast a major restructure of existing arts organisations.

On January 26 1973, Whitlam announced the establishment of the interim Australian Council of the Arts. A range of autonomous craft-specific boards would sit under it – Aboriginal arts, theatre, music, literary, visual and plastic arts, crafts, film and television – with the renowned arts administrator H.C. Coombes as its inaugural head.

After years of delay, a newly appointed interim council for the National Gallery began work in 1973 on the new gallery, with James Mollison as interim director.

Read more: James Mollison: the public art teacher who brought the Blue Poles to Australia

This was just the beginning of “a cultural sea change” in the arts.

There would be reforms in radio with Double J, later Triple J, and the first “ethnic” broadcasting in Australia through 2EA and 3EA.

The film industry was rebooted through the establishment of the Australian Film Commission, the Australian Film & Television School and Film Australia, and an increase in the quota for Australian made television and films.

The Public Lending Rights scheme was introduced to compensate authors for the circulation of their works through libraries.

Kim Williams describes the “innovative thinking” behind the close involvement of arts practitioners in policy development and administration as:

a new ground plane for empowered decision making by artists in a profoundly democratic action for the arts.

A new choice

At a time of relentless funding reductions, cost-cutting and job losses, renewal and revival is desperately needed across our most important cultural institutions.

The dire effects of this decade of neglect can be seen most starkly in the 25% staff cuts and under-resourcing of the National Archives of Australia which, as the highly critical Tune review made clear, has led to the disintegration of irreplaceable archival material including recordings of endangered Indigenous languages. The 2022 budget only continued those reductions.

We are again at a time when renewal and reinvigoration of the arts is urgently needed – yet it has scarcely featured thus far in this campaign.

The Liberal Party’s policy statements do not feature the arts. In contrast, Labor’s Arts policy, announced last night, promises a “landmark cultural policy” which would restore arms-length funding, explore a national insurance scheme for live events and ensure fixed five-year funding terms for the ABC and SBS.

There is a choice for the arts on 21 May between stasis and renewal. I’ll take the renewal, and hope it becomes a renaissance.

Read more: Why arts and culture appear to be the big losers in this budget

Jenny Hocking receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.