Leon Kossoff, one of the leading figures in Post-World War Two figurative art in Britain passed away in 2019. LA Louver in Venice, CA is now exhibiting the largest gallery show and first posthumous survey of Kossoff’s work, Leon Kossoff: A Life In Painting (on view until April 9, 2022). Organized in collaboration with Annely Juda Fine Art in London and Mitchell-Innes & Nash in New York, the show was curated by Andrea Rose, the former Director of Visual Arts at the British Council.

Kossoff is often grouped in “The School of London” Painters, a nomenclature suggested by the painter R. B. Kitaj in the 1970s that included Kitaj, Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, a generation of painters who attended British Art schools and made representational and figurative work that confronts the existential grimness of post-World War Two Britain. Ironically, of all the painters mentioned above, Kossoff was the only one actually born in London, in Islington in 1926, the child of Jewish immigrant parents from Lithuania and Ukraine.

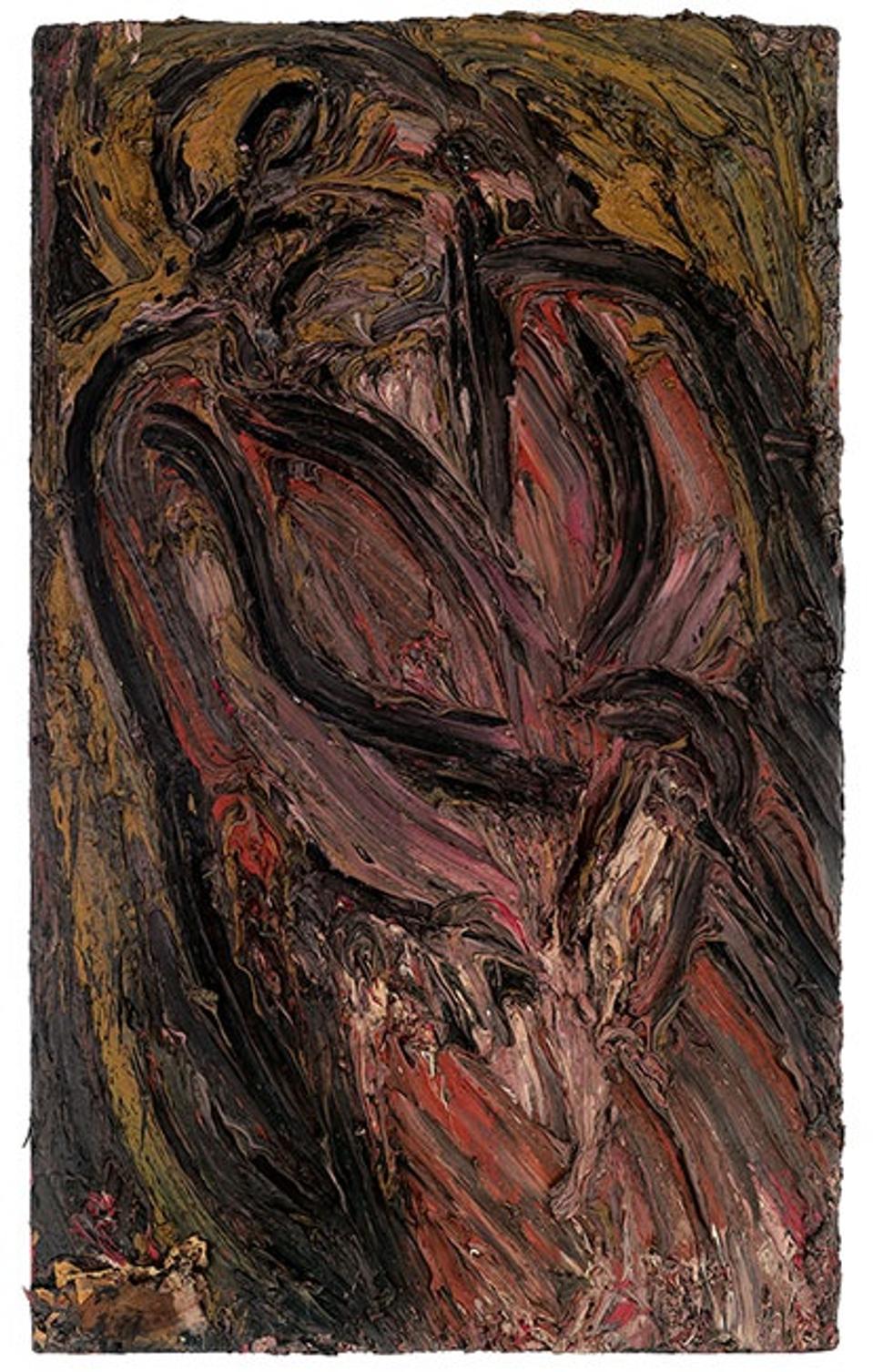

The greatness of Kossoff’s work is revealed in how his images emerge from the impasto – the accumulations of thick layers of paint — forcing the viewer to negotiate and cycle back and forth between the image depicted and the paint itself.

In the earliest paintings on exhibit, Seated Woman, and Woman Ill in Bed, both from 1957, it is as if the subjects were themselves struggling with the paint, or as if the paint itself was a manifestation of Kossoff’s subjects spiritual and physical condition.

A recent article on Charles Dickens in The New Yorker made the point that during the Victorian age, London streets were muck-filled, the rivers polluted, and the thick fog pervasive. After the Blitz, the London that emerged from World War Two was busy with construction sites rebuilding the War-caused rubble of the devastated yet enduring City. Kossoff’s palette reflects the dark greys of concrete dust, the earth browns and muddy greens of a combustible London.

One the one hand, Kossoff’s portraits make one think of the figurative expressionism of Willem de Kooning; on the other, in his London street scenes, it is as if Monet had chosen to paint Willesden Lane and Kings Cross rather than the Cathedral at Chartres. Kossoff displays great affection for those sites in London that others might find unattractive or down-market. This is very much apparent in Kossoff’s 2006 painting Kings Cross Building Site, Early Morning, that seems to shimmer. It is as if Kossoff is saying, “This my London. The real London.”

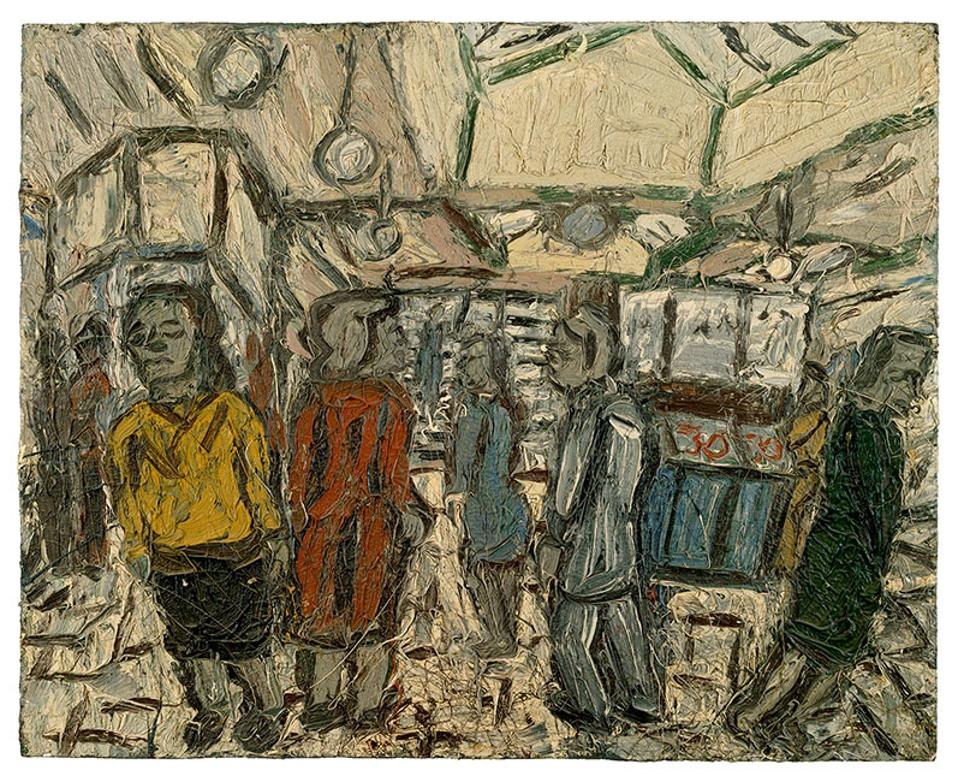

My favorite painting in the exhibition Booking Hall, Kilburn Underground Station no. 4 from 1978, is a masterpiece of Kossoff’s art, capturing the bustle of a subway station and rendering the half dozen or so figures in a way that is crude, primitive and almost cartoon-like yet captures reality as well as any Impressionist painting. The same is true in A street in Willesden No. 1 from 1983.

Kossoff’s 1971 painting, Demolition of YMCA Building No. 2, could have been a dour account of destruction. Instead, the energy and vigor of the brushstrokes, and his strategic use of reds and blues make for a celebration of creation, of rebuilding, of the transformation of London itself.

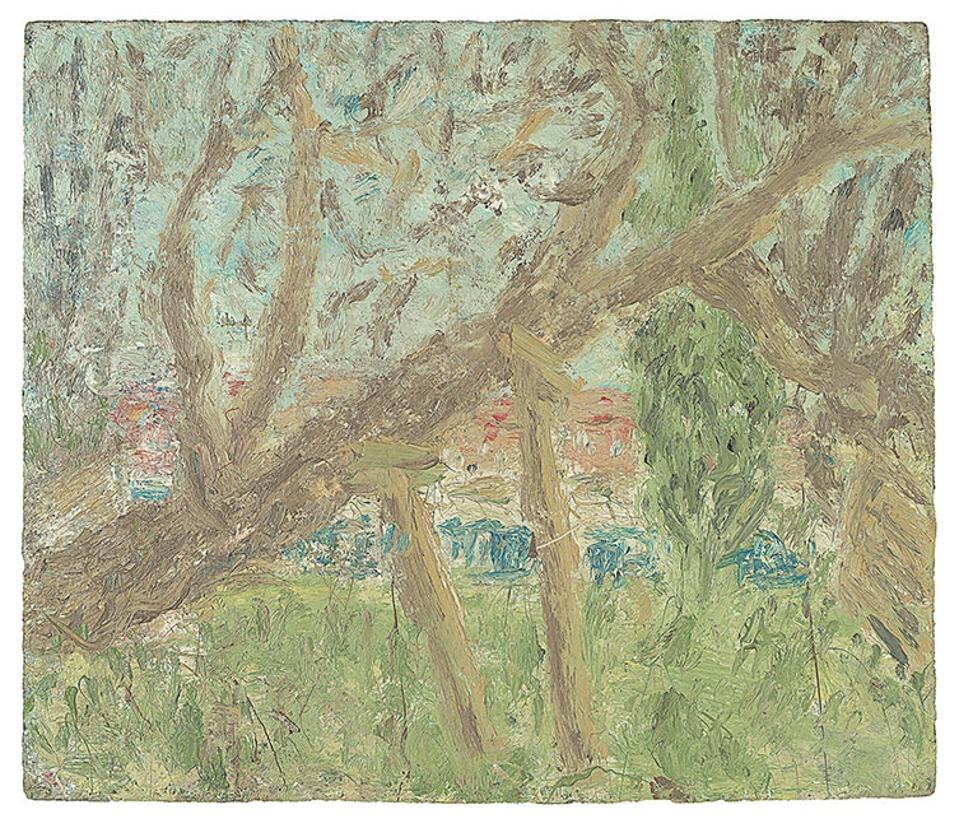

Kossoff displays great warmth and affection for his subjects, often friends and family members, such as his portraits of Peggy from 1969, and 2004, and Kossoff’s portrait of Peggy and John from 2006. The LA Louver exhibition also features several self-portraits by Kossoff, in which his seriousness shines through. In the last paintings Kossoff made, of branches of cherry blossoms, there is a lightness that appears to speak to a journey from his earliest dark paintings to acceptance and hope of spring.

The Kossoff exhibition at LA Louver features two paintings Kossoff made inspired by Poussin Pan-themed works. Upstairs the gallery showcases a suite of Poussin Pan inspired drawings, no less impressive than his paintings in Kossoff’s ability to suggest movement and emotion.

The exhibition also celebrates the publication of a catalogue raisonné of Kossoff’s work organized and assembled by Rose, which lists the 510 known oil paintings Kossoff produced during his lifetime, with images of each, exhibition history, and a list of its successive owners, as well as comments on the work by prior owners, critics, art historians and curators.

As we emerge from this pandemic into a ravaged world, filled with conflict, war and destruction, Kossoff reminds us of the tonic and potency of rebuilding and that art can be a celebration unto itself.