In December 1855, 31-year-old Dr William Palmer was arrested for the murder of his racing crony John Cook. Both men had attended a meeting at Shrewsbury, where Cook’s horse won, netting the enormous sum of £3,000. Palmer lost, thereby descending deeper into a vortex of debt and the clutches of threatening money lenders. Breaking his return home in Rugeley, the small Midlands town where Palmer lived, Cook subsequently fell ill; five days later, he died there in writhing agony.

Cook’s stepfather already distrusted Palmer and arrived in Staffordshire to find the young man’s betting book and papers were missing. The housemaid said Palmer had given Cook pills – he had also sent a broth that (because she had stuck her finger in it to taste) had made her violently ill. No one yet knew that Palmer was already claiming Cook’s recent winnings as his own, but tongues began to wag – for there had already been too many deaths in the Palmer family. His wife, Annie, had sickened and quickly died the previous year – just one premium paid on her life insurance –and only one of her five babies had survived more than a few weeks. Then Palmer’s alcoholic older brother, Walter, also expired soon after purchasing a new life policy. Sceptical, the insurance company refused to pay out, threatening a criminal investigation they failed to pursue.

At Cook’s post-mortem, most of his stomach contents were spilled when one of the doctors was barged from behind, ostensibly by Palmer. Apparently panicking, he tried to bribe the boy carrying samples for analysis to overturn the cart and smash the bottles and, when that failed, importuned the postmaster to intercept the chemical report sent to the county coroner. Then a chemist’s assistant admitted selling Palmer strychnine the week before. As suspicion bloomed, Annie and Walter’s bodies were exhumed.

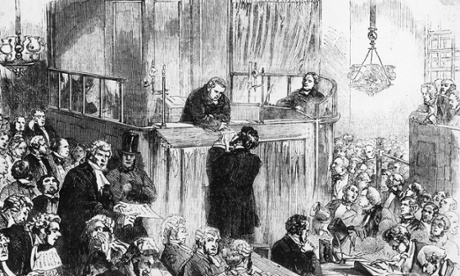

His trial at the Old Bailey in 1856 was one of the great Victorian legal showpieces. It pricked the public interest because strychnine, the alleged poison, was new and barely understood. Scrutiny of the case was all the more intense because fear of poisoning had grown to something of a mania by mid-century, and because Palmer was one of a “new breed” of bourgeois villains.

Whether he had killed two or 20, Palmer could only be tried for one murder at a time. The jury found him guilty of Cook’s murder and he was returned to Stafford to hang. A smart writer, Bates skilfully unpicks the events that led up to Cook’s death, though he brushes over the “poisons panic” of the 1840s, flourishing contemporary debates about press prejudice, and the fallibility of direct and indirect proof. Once dubbed the “prince of poisoners”, Palmer ultimately emerges as amoral rather than depraved; less Harold Shipman than a desperate man “brought low by his own venality, by chance and fate”.

The Poisoner: The Life and Crimes of Victorian England’s Most Notorious Doctor is published by Duckworth (£16.99). Click here to buy it for £13.59