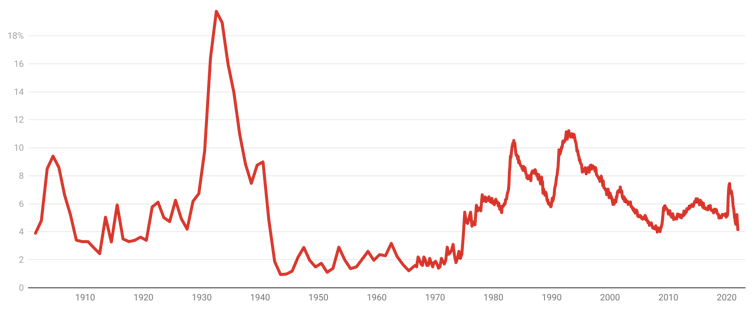

Australia’s unemployment rate – now at 4.2% – is at its lowest in more than a decade. It’s not too far off slipping below 4%, something that hasn’t happened for the best part of half a century.

This good news story has ignited fierce debate over who deserves the credit.

The prime minister and the Reserve Bank governor believe it is them. They delivered both the biggest government stimulus package in history and the lowest interest rates in history.

Australia’s unemployment rate, 1901 to February 2022

But others disagree, most notably ACTU Secretary Sally McManus who tweeted last week that the reason unemployment rates were low was closed borders.

It had “nothing to do” with economic management.

So who’s right? No matter how we run the numbers we find it’s economic management. On balance, closed borders might have helped us, but because they prevented Australians from leaving, rather than others from arriving.

Arrivals boost demand as well as supply

New arrivals (often migrants) most certainly do add to the supply of labour. They compete with pre-existing Australians for jobs.

But that’s only half the story.

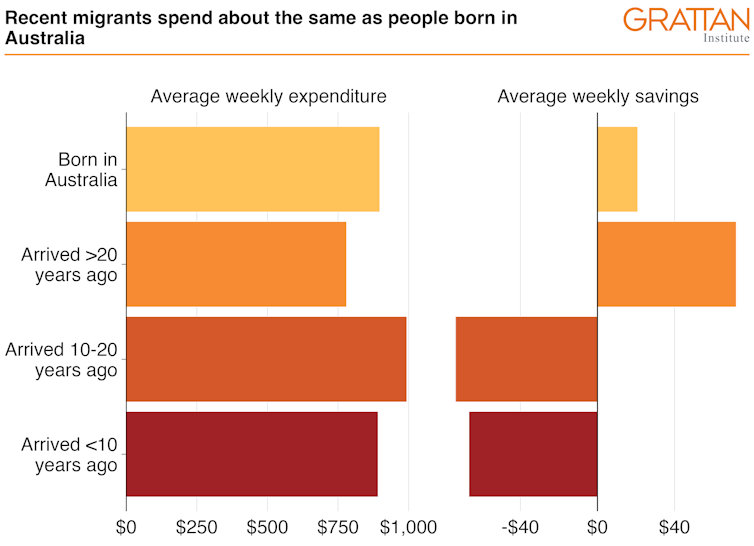

The other half is that new arrivals consume goods and services, for a while at a greater rate than Australians who have been here longer. They save less or run down savings in order to do it.

Read more: The government is right – immigration helps us rather than harms us

By buying more, they add to the demand for goods and services, and for workers to produce them.

If migrants enter Australia to work, but then spend more than they are paid, they might even create more jobs than they ‘take’.

The net effects are small

Most recent research confirms that migrants both take and create jobs, finding little overall impact on the employment or wages of existing workers.

One study even found temporary skilled migrants boosted the wages of lower-skilled Australians by prompting them to move up into higher-paid jobs.

In an in-depth study conducted in 2016, the Productivity Commission concluded

there was almost no evidence that immigration is associated with worse (or better) labour market outcomes for Australian-born people

Of course, the pandemic is a unique event. Research only takes us so far.

But in Europe and the United States where borders remained open, unemployment also fell to near historic lows, suggesting it was something other than closed borders that did it.

But staff shortages are real

The number of migrants fell dramatically after COVID began. This reduced both the supply of and demand for labour, but the composition affected some industries more than others.

Before the pandemic, about one in six workers in hospitality were temporary migrants, many of them international students.

There are roughly half as many international students in Australia now as in 2019. Working holiday makers, who made up about 4% of the agriculture workforce, are almost entirely absent.

The staff shortages are real. Labour supply in those sectors has dramatically shrunk while demand for their services has continued. Eventually those employers will make other arrangements or the supply of backpackers and international students will resume.

Closed borders helped, by keeping Australians here

Oddly, there was an aspect of closed borders that boosted GDP.

As it happens, Australians spend more overseas each year than Australia makes from tourists coming here.

As economist Saul Eslake points out, banning our population from leaving has been a perverse windfall. Money that would have otherwise been spent overseas has been spent at home.

Bureau of Statistics figures suggest that closing the border might have contributed $28 billion to Australia’s trade balance compared to 2019.

It’s stimulus that mattered

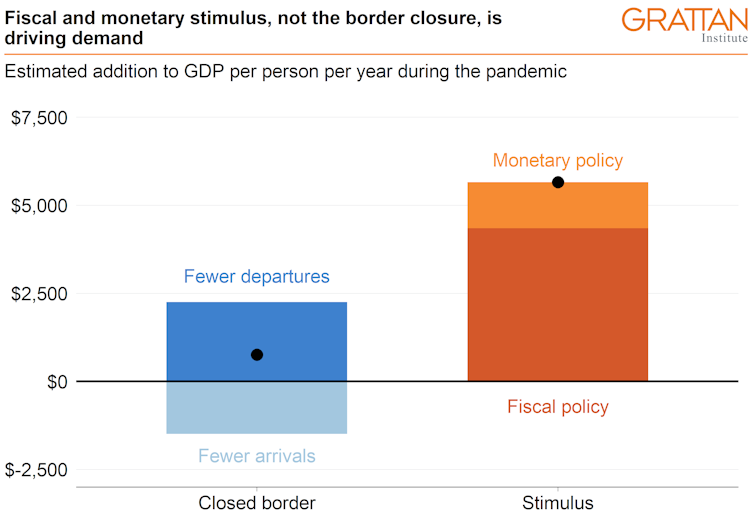

Putting the story together in the chart below, it’s clear that stimulus (both “fiscal” from the government, and “monetary” from the Reserve Bank) boosted the economy far more than did closed borders.

The dark-blue bar captures the decline in spending overseas on travel and education as fewer Australians travelled, while the light-blue bar captures both the decline in spending on Australian education and travel, and the effects of fewer working migrants, as fewer visitors arrived.

Both are swamped by stimulus, which is marked in dark and light orange.

The Federal Government set aside $291 billion for stimulus payments. Including tax breaks and state government support, the International Monetary Fund comes up with a total of $362 billion.

While some JobKeeper ended up in the hands of shareholders, the scale of the stimulus cannot be denied. Assuming a relatively conservative fiscal multiplier of 60 cents for each dollar of fiscal support, these supports are set to boost Australian gross domestic product by $217 billion, or roughly $8,600 per person.

The Reserve Bank’s actions might have added $70 billion to GDP over two years. Without these supports the economy would have found itself in a huge hole during the pandemic.

Read more: Unemployment below 3% is possible – if Australia budgets for it

Our low unemployment today is a testament to the success of economic policy.

Attributing it to closed borders runs the risk of leaving us with the wrong lesson the next time the economy turns down.

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments, $4 million from BHP Billiton, and $1 million from NAB. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute's board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and contribute to funding Grattan Institute's activities. Grattan Institute also receives funding from corporates, foundations, and individuals to support its general activities, as disclosed on its website.

Alex Ballantyne and Will Mackey do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.