In a photograph taken in the mid-1930s, a young woman in a striped swimsuit sits in the shallows of a river near the Russian city of Sverdlovsk, which reverted to its original name of Ekaterinburg in the 1990s.

Her hair is short and curled up around the back of her head and ears, in keeping with the European fashion of the time. One hand is stretched out to cover that of a young, tanned and good-looking Chinese man. It’s her husband, Chiang Ching-kuo, the son of China’s Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek. Faina Ipat’evna Vakhreva would be married to him for the next 53 years.

Hers was an extraordinary life – a Russian factory worker propelled from a life in the Soviet Union under Stalin to a member of China’s first family. Later, during the communist revolution in China, she and her husband fled to Taiwan where, under martial law, Chiang Ching-kuo would succeed his father as leader of the Republic of China.

“Her whole life was about adjusting, about completely changing who she was,” says writer and China analyst Mark O’Neill, who has written her biography, China’s Russian Princess: The Silent Wife of Chiang Ching-kuo, published by Joint Publishing in Chinese and English.

It is an empathetic portrait of a woman whose life was never easy. An orphan born into poverty and hardship in East Belarus in 1916, she would have four children, three of whom – her three sons – would die before her. While her life had all the trappings of privilege and power, she appears to have been happiest as a frugal housewife.

By telling her life story, O’Neill also paints a picture of Soviet Russia and Stalin’s Kafkaesque policies that made Chiang Ching-kuo a political prisoner in the Soviet Union for years before his life continued in China.

“The story of Chiang Ching-kuo is well known and it would be hard to write something new about him,” O’Neill says. “But his wife is a secret and so a better topic for a biography. Without her, he would not have been who he was.”

O’Neill has lived in Asia for more than 40 years. He came to Hong Kong in 1978 to work for broadcaster RTHK and three years later moved to Taiwan to learn Mandarin. He recalls being on the island under martial law when Faina, who became First Lady of the Republic of China in 1978 upon her husband’s appointment as president, was an enigmatic figure seen by few.

During his time on the island and on his many subsequent visits, O’Neill became fascinated by the president’s family and by Faina. He spoke to people in the community, but little was known about her other than that she might be foreign.

He tried those who would have known her through her husband, including former president Ma Ying-jeou and veteran politician James Soong, but interview requests were declined. He finally succeeded with Faina’s daughter-in-law, Elizabeth Chiang, among others, who described her mother-in-law as lively and fun loving, often telling jokes at home in either Russian or Chinese.

She never returned to Russia after leaving with her husband and young son in 1937. And this was not the life she was expecting - Mark O’Neill

The story of Faina, who later became Chiang Fang-liang, is of course also the story of her husband. In her, he found an unquestioning and loyal supporter throughout his life, despite major challenges, periods of separation and his repeated infidelity.

O’Neill says that in Chiang Ching-kuo’s memoir, My Life in the Soviet Union, he described Faina as his only friend at the Ural Heavy Machinery Plant in Sverdlovsk – where the Soviet government had sent him to work during his detention – where he was her supervisor in the early 1930s.

“We met after she graduated from a workers’ technical school. I was her superior. She was the person who most understood my situation. Whenever I experienced difficulties, she always expressed sympathy and a willingness to help,” he wrote.

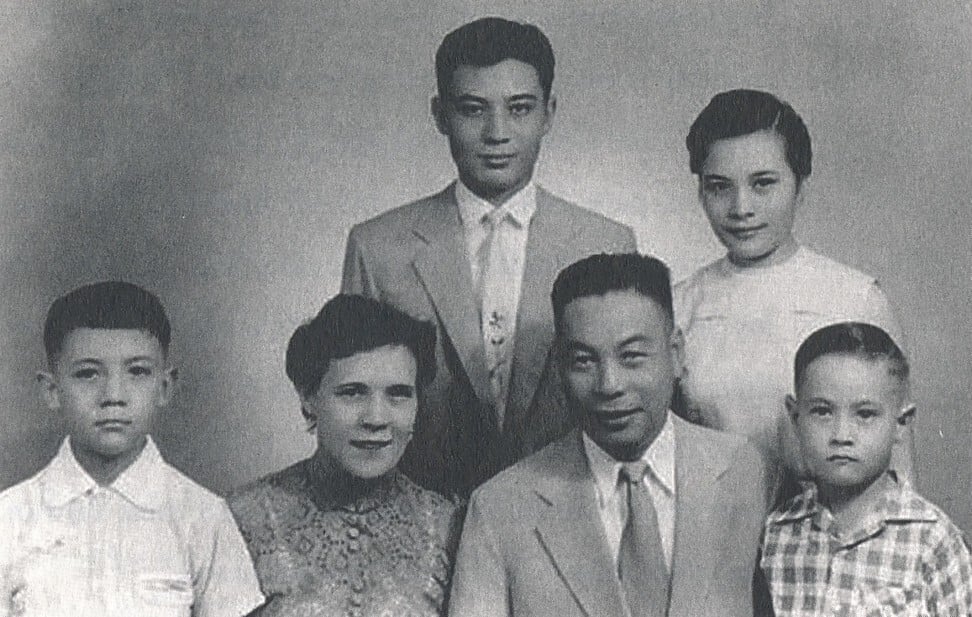

China’s Russian Princess is an easy read, despite the intricate politics of the time. Intimate family photos were provided by the Academia Historica, the digital archive of government documents in Taipei.

O’Neill conducted interviews and drew on various biographies for his book. Unfortunately, Faina didn’t leave her own journal for him to delve into.

She had been brought up by her older sister and lived in grinding poverty during her early life. Her future husband came to the Soviet Union at the age of 15 to study communism at the Sun Yat Sen University in Moscow. Chiang Kai-shek had visited Russia in 1923 to buy weapons, and decided to send his son there to study.

“He had been impressed by what he saw, how this industrialised collection of countries was moving forward since the overthrow of the Tsar and the killing of his family after the Bolshevik revolution of 1917,” O’Neill says.

Deng Xiaoping was one of Chiang Ching-kuo’s classmates, and on one occasion the future leaders of China and Taiwan walked along a frozen river in Moscow and talked.

In Faina, Chiang Ching-kuo – who spoke fluent Russian and enjoyed vodka – found a fun-loving, sociable young woman who liked ice skating and hiking.

They married in 1935 and lived in a small flat in Sverdlovsk. Life in Soviet Russia was hand to mouth, and there was never enough food. After their first son was born, Chiang wished to return to China, but Stalin held him hostage. He had “become a piece in the complex and Machiavellian game of Soviet politics and diplomacy”, O’Neill says.

Life under Stalin was hideous for the couple. Friends were executed and Chiang Ching-kuo lost his job and his party influence after being accused of spying for the Japanese, among other things.

It came as a shock when Stalin finally allowed him to go home. Faina left Russia with him and was propelled into life with China’s first family.

“She never returned to Russia after leaving with her husband and young son in 1937,” O’Neill says. “And this was not the life she was expecting. She was expecting to live the rest of her life with her husband in the Soviet Union.”

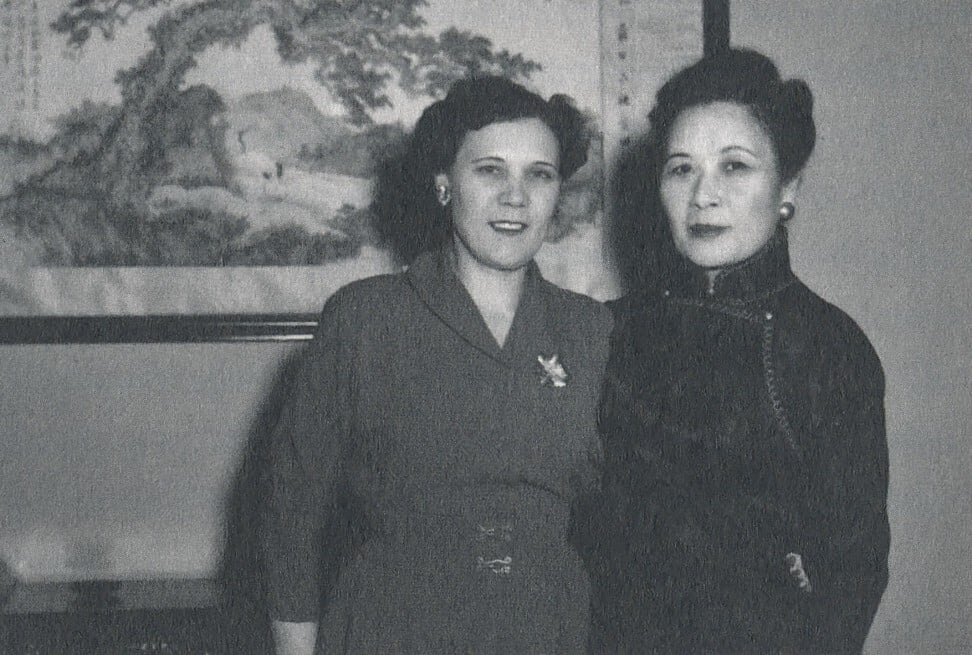

O’Neill chuckles at the surrealness of Faina heading to Beijing and meeting her mother-in-law, the sophisticated and all-powerful Soong Mei-ling, Chiang Kai-shek’s third wife, who was at home among presidents and prime ministers.

“So she arrives in China, she’s from an ordinary family, she does not speak Chinese and suddenly she meets Soong Mei-ling, the most poised Chinese woman in the world,” O’Neil says. “She is wealthy, well-dressed, at ease with everyone, and suddenly this Russian factory worker is meeting her [as a] mother-in-law.”

Chiang Kai-shek loved his grandson, Faina’s son, and O’Neill speculates that without the boy, Faina might have quietly disappeared from the scene and a more suitable wife from China’s senior families would have been found. As it was, the new daughter-in-law immersed herself in the language and culture of her new home, and took up Chinese painting and mahjong.

The young couple and their son went first to Zhejiang province to stay with Chiang Ching-kuo’s mother, Mao Fumei. Local women were scandalised by this young blond Russian, pregnant, bathing in the river and riding a horse through the villages.

As Chiang Ching-kuo was given increasing responsibility by his father, Faina became active as the local civic leader’s wife. Her time there was marred, however, by her husband’s affair with a fellow worker that resulted in twin boys. The other woman then died mysteriously.

Faina’s role diminished when the family went to Chongqing in southwest China, where Chiang Ching-kuo became his father’s key adviser. There were periods of loneliness and isolation in her life, and this was one of them. Then, as the communist army increasingly won Chinese territory, Faina was sent ahead with her children to Taiwan.

“This was somewhere she had never been and there followed a harrowing eight months while she awaited news of her husband,” O’Neill says. Communist spies were rife in the Kuomintang, so the whereabouts of her husband and father-in-law were kept secret and she had no idea where they were during this dangerous period.

Once in Taiwan, Chiang Kai-shek’s controversial rule began with tens of thousands of people imprisoned and thousands executed during the period of “white terror”. His son also played a role but is more fondly remembered by the populace.

[Her husband] asked her not to ask him about his political and public life and she complied, loyally accepting her role as housewife and mother - Mark O’Neill

Faina’s two older sons were spoiled, gun-loving, partying young men, however. O’Neill writes that they felt the accomplishments of father and grandfather weighing on their shoulders.

All three sons died early from diabetes and cancer. O’Neill discovered that some Taiwanese feel it was divine retribution for their grandfather’s behaviour.

As for Faina, she initially enjoyed the chance to play golf, go bowling and walk to the shops. She tried to curb her husband’s love of alcohol and confectionery as his diabetes wrought havoc with his health. Herself a heavy smoker, she had asthma and became increasingly isolated.

“[Her husband] asked her not to ask him about his political and public life and she complied, loyally accepting her role as housewife and mother,” O’Neill says. He also reveals that Faina’s elder sister, who had raised her, wrote to her in Taiwan, the first communication in 30 years, and Chiang Ching-kuo decided not to give her the letter.

O’Neill describes that Faina never lost the frugality of her early years and even asked servants to show her the bill if she thought too much had been spent on food.

Faina’s bond with her husband endured into old age. Elizabeth Chiang, who was married to Faina’s third son, told O’Neill that Faina would “wait by the door” for her husband, and they shared jokes in Russian and Chinese.

Faina died from complications of lung cancer at the Taipei Veterans General Hospital on December 15, 2004, aged 88, having outlived her husband by 16 years.