With a little more than 10 minutes remaining in the fourth quarter against the Cardinals last week, Jimmy Garoppolo lined up under center with fullback Kyle Juszczyk and running back Christian McCaffrey directly behind him. Just before the snap, Juszczyk danced just slightly to his right, signifying the 49ers may run some kind of toss or stretch play to that side. Just after the snap, McCaffrey darted at the football like he was going to take the handoff and follow his fullback.

Every member of the Cardinals’ defense crashed the run, while tight end George Kittle, who was also lined up on the right—additionally keying a run play to that side—began darting to his left away from the play. The 49ers had run a similar-looking play to the opposite side of the field earlier in the game, which likely heightened the confusion for Arizona’s defense.

This time the run was a fake, and Garoppolo held on to the ball, bootlegging toward his tight end (according to Pro Football Reference roughly 17% of Garoppolo’s passing attempts have come off play-action—well below the league average of 27%—which helps maintain the play fake’s potency). Undetected, Kittle found himself a small enclave of space, caught a pass and began to rumble down the left sideline.

After the first few yards of running with the football, it was clear no one on the Cardinals was signing up to tackle Kittle without the help of a Kevlar vest. Two of their defenders’ attempts were so poor that they drew the ire of color commentator Troy Aikman as he reviewed the replay of the 32-yard touchdown pass.

Mike Comer/Getty Images

It was Garoppolo’s fourth touchdown of the day and a continuation of the narrative that he’s been on a tear of late. The truth is somewhat more complicated. That touchdown, the process of getting Kittle open along with, as Aikman pointed out, the reluctance of the Cardinals to try to tackle the tight end, tell a more realistic version of the story.

Put simply: During the best years of the Kyle Shanahan regime in San Francisco, it has always seemed like Garoppolo was ever so slightly holding the team back, enough so that Shanahan and the team brass sacrificed multiple first-round picks to select his presumed replacement, Trey Lance. Forced to go back to Garoppolo when Lance fractured his right ankle in the second game of the 2022 season, Shanahan has built an offense—and a team—that would largely protect the quarterback from altering the equation.

To Garoppolo’s credit, the quarterback play in San Francisco has stabilized. He is, according to Football Outsiders, third in the NFL in yards above replacement. A composite of his expected points added per down and completion percentage over expectation is the seventh-best in the NFL (though, tellingly, Garoppolo is the only quarterback in the top 10 without a positive completion percentage over expectation rating). Garoppolo follows the Shanahan Rules and makes few mistakes, but even on bad play calls against the wrong defense when Garoppolo throws to the incorrect wide receiver, the mistakes don’t seem to matter. The play can still be a success.

Because of this, we are looking at a 49ers surge as much about economics as schematics. It says plenty about how Shanahan has grown into one of the elite head coaches and team designers in the NFL. It also says something significant about where the NFL is right now as a league.

We are left with no choice but to consider the 49ers legitimate Super Bowl contenders no matter who is taking snaps and throwing the football (within reason). Here is a look at why and how we arrived at this point.

Heading into Week 11, Patrick Mahomes averaged 326 yards per game, with 160 of those yards coming from whatever his receivers do after the catch. In other words, 49% of Mahomes’s weekly passing yardage is dependent on receivers turning upfield and picking up additional yardage.

Josh Allen averages 293 yards per game, with 170 of those yards coming after the catch (58%).

Garoppolo averages 241 yards per game. However, just 93 of those yards come before the catch, according to statistics provided by Sports Info Solutions. More than 60% of his total yardage depends on the catch-and-run ability of his best receivers.

Garoppolo has one of the lowest intended air yards per pass totals in the NFL, at just 6.9 (Tua Tagovailoa and Josh Allen, for example, hover around nine intended air yards per attempt). Garoppolo also has one of the lowest air yards to the sticks averages, meaning how much shorter he throws each ball than the first down marker (minus-2.1). Only Kyler Murray, Daniel Jones, Baker Mayfield and Matt Ryan throw shorter in relation to the sticks than Garoppolo.

But rather than turn this into an indictment of the quarterback, consider what the 49ers are looking at in terms of their roster, what they are seeing from opposing defenses, what league-wide coverage trends look like and what resources they have at their disposal.

Kyle Terada/USA TODAY Sports

Back in March, we declared that 2022 would be the year of the checkdown (and, in particular, a big year for players like McCaffrey and Saquon Barkley). The reasons were simple: (1) More good quarterbacks coaches were preaching the advantages of short, easy completions, and (2) more defenses were playing two-high shell defenses, which offer offenses vast amounts of real estate in the short and intermediate portions of the field right in front of the quarterback in exchange for placing a hard cap on the offense’s big-play ability. This was going to unleash a reliance on short passes to bludgeon teams out of their insistence on two-high coverages.

The 49ers were already uniquely suited to play this kind of game. Kittle is among the best tackle-breaking tight ends in NFL history. At one point in 2020, Kittle and teammate Deebo Samuel were, statistically, the two most prolific tackle-breakers in the NFL. Through Week 11 this year, Samuel was third in the NFL in broken tackles as a pass catcher, and also breaks one in every 10 tackles when he gets the ball as a runner, which is among the top 10 percentage-wise. McCaffrey, whom the 49ers traded for in October, is seventh in broken tackles as a receiver and 16th in broken tackles on running plays.

One would think that was a sound enough strategy on its own—find people who are punishing or difficult to bring down and feed them the ball consistently in open space with short-distance throws.

But there is something else we’re missing. Something the 49ers seem to understand better than most.

It has been declared by your nostalgic-uncle types for decades now. In their minds, football was more chaotic and violent back when they played in barely functioning plastic helmets, with every down like a beach-storming scene from a World War II epic. Ask them to describe a hit they laid on someone in high school; it’s better than any scene in Any Given Sunday. They watch the modern NFL with fists balled and teeth gritted. And, they are, unfortunately, kind of right: Defenses don’t really tackle that well anymore.

This year, according to Sports Info Solutions (and my questionable attempt at math), the NFL’s leader in missed tackles is on pace for 37. Last year, the NFL’s missed tackle leader had 39; there were four players with more than 30 missed tackles.

Consider that in the three years before, the NFL averaged about 1.6 players per year with 30 or more missed tackles.

According to Pro Football Focus, back in 2010, 31 of 32 teams achieved a tackling grade that rated between mediocre (65 in PFF’s grading system) to excellent. By ’15, 18 teams had a 65 tackling score or better. In ’20, there were only eight teams that had achieved a 65 or better. There are 10 this year. There were 10 last year as well.

The reasons are myriad. Practice time has been shaved to the bare minimum. Coaches are largely afraid to practice live tackling because they are so dependent on their starters and need to keep them healthy. Injury rates, aided by poor turf conditions, are on the rise, forcing more ill-prepared backups onto the field.

Kelley L Cox/USA TODAY Sports

Play-callers, like Shanahan, are also better equipped than ever to provide their receivers and backs with open space and room to run. While San Francisco sees slightly more single-high Cover 1 coverages than two-high safety looks, according to SIS DataHub, the basic idea is the same. They are already good at creating room to run, they are handed additional space when defenses give them the most popular schematic look of the moment and they are detonating it.

Watch the 49ers live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today.

This brings us back to Kittle’s touchdowns against the Cardinals. Like so many of the 49ers’ explosive plays, it relies on history and precedent. San Francisco knows its own tendencies as well as the tendencies of the gutted and depleted defenses it faces on a regular basis. After adding an elite running back in McCaffrey to the fold, every snap becomes an event, a few lines of code in their defensive malware. A motion, a fake handoff, a step in one direction or another. From a defensive perspective, they are looking at a kaleidoscope of indicators, keys, misinformation and subterfuge, and by the time they can grasp onto something real and concrete, a player has slipped out of the backfield and has taken hold of the football.

By the time that happens, defenders are deciding whether they are willing (or even capable) of hurling themselves in front of a locomotive. By the time that happens, the unlucky defender is already under the tracks.

It’s too simplistic to say Garoppolo only hangs back and throws the ball to teammates at the distance of a common basketball chest pass. However, it is fair to say when this does happen, the 49ers are more dangerous than any other team in the NFL.

Every year, the Super Bowl participants are not necessarily the most talented (though talent matters) but the best suited for the schematic landscape of the NFL.

Last year the Bengals were among the early teams to adopt coverage-heavy defenses, thanks, in part, to a formidable four-man—or, at times, three-man—pass rush. Joe Burrow was also adept at pushing the boundaries of those defenses and exploiting the limited vacant downfield space. The Chiefs had the personnel to knife the Pete Carroll Cover 3 defenses popular at the time of their title. The Buccaneers capitalized on their glut of talented off-ball linebackers who could help them overcome some of the disadvantageous personnel groupings defenses could try to put them in.

What we have in San Francisco is somewhat more concerning to the rest of the league. Tackling is probably not going to get better. Defensive coordinators are more likely to continue coveting zone-heavy schemes that prevent them from getting publicly embarrassed by a big play. If the 49ers have some kind of high-level physics equation to determine which collegiate players will smash through tackles at the next level, they can operate a conveyer belt of catch-and-run threats to take them to the playoffs year after year.

Godofredo A. Vásquez/AP

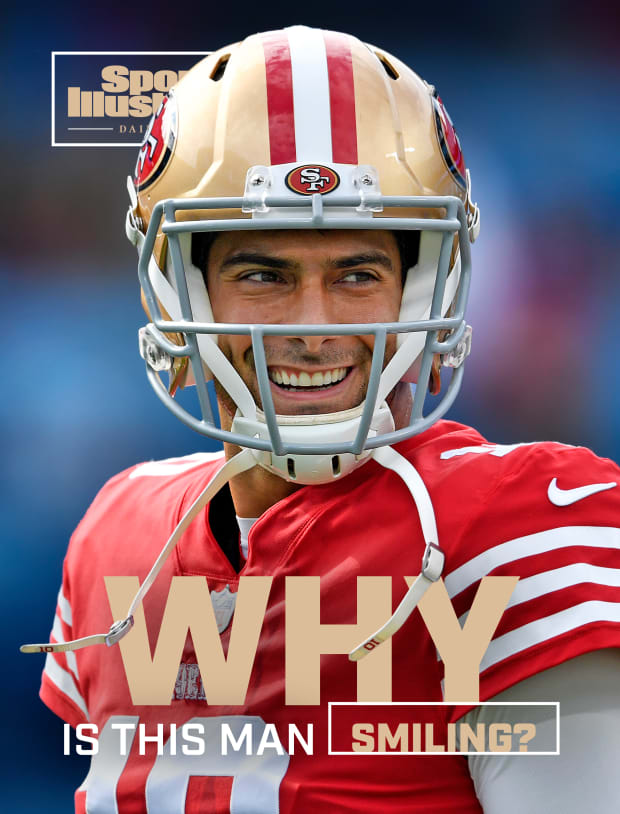

On Sunday the 49ers beat the Saints 13–0 behind a dominating performance by the defense. For Garoppolo, there was an ill-advised decision to scramble on a fourth-and-goal resulting in a turnover on downs, his lone touchdown pass first bounced off the hand of a defender, and he had a particularly ugly would-be interception erased by a New Orleans penalty. He completed 26 of 37 passes for 222 yards, his average of six yards per pass attempt a full yard less than opposing quarterback Andy Dalton. And there he was after the game, being interviewed on the field, flashing the smile of a pool salesman in a pandemic.

This was the smile of a quarterback who hasn’t lost a game since before Halloween. The smile of someone who was trade bait just a few short months ago and who will emerge onto the 2023 free-agent market as something of a commodity. The smile of someone who, ultimately, knows he is in the right place at the right time.

Editors' note, Nov. 28, 12:16 p.m. ET: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the injury Trey Lance sustained in Week 2 as a torn ACL. Lance sustained a fractured right ankle.