The twangy grandeur of Zal Yanovsky’s big guitar riff on the Lovin’ Spoonful’s You Didn’t Have to Be So Nice made it a Top 10 hit in the winter of 1965-’66. The track also caught the ear of Brian Wilson, inspiring him to write the Beach Boys classic, God Only Knows. Another Spoonful hit, Daydream, influenced Paul McCartney as he was putting together the Beatles’ Good Day Sunshine, from their groundbreaking 1966 album, Revolver.

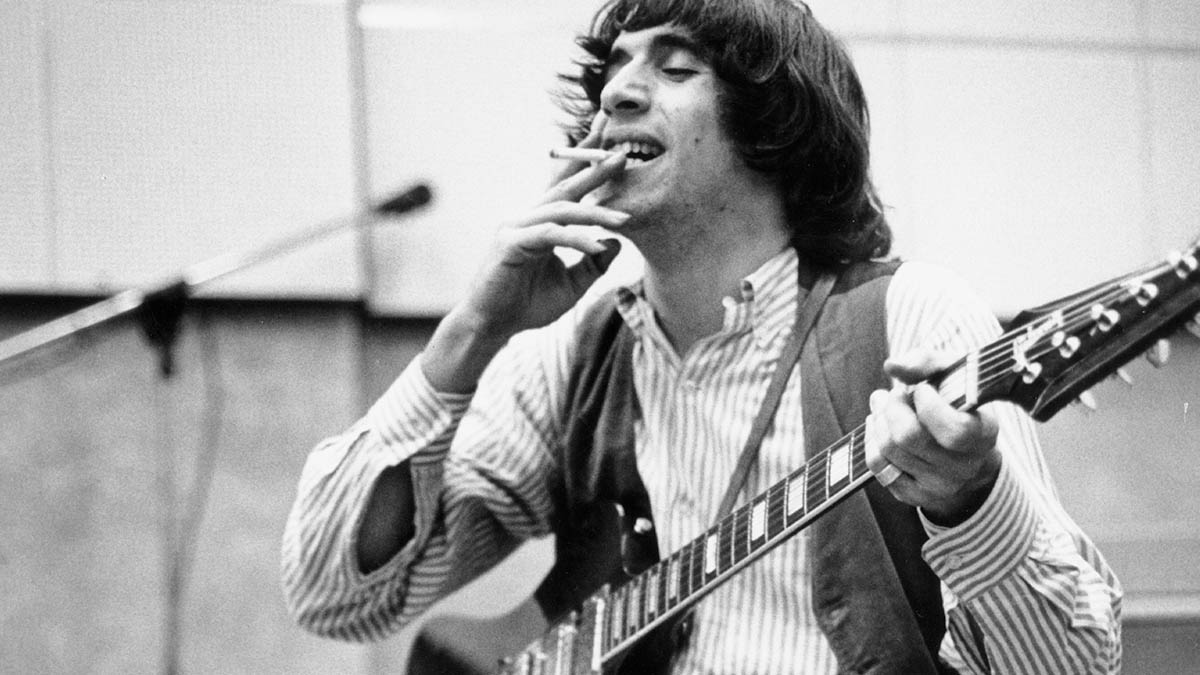

In the mid-Sixties, the Lovin’ Spoonful were one the most innovative and well-regarded bands around. Yanovsky’s whimsical, wild, wistful and weird guitar work was no small part of the quartet’s popularity. It was the sunshine in the band’s self-described Good Time Music.

Sweet, weepy country licks, amped-up blues, fuzzed-out psychedelia.... Yanovsky’s broad stylistic range proved the perfect counterpoint to frontman John Sebastian’s wry, folksy songcraft, multi-instrumental palette, and fine-tuned gift for pop melodicism.

Even in the non-conformist Sixties, Zalman Yanovsky stood out from the crowd, with his boho-hobo-cowboy fashion sense, clownish on-stage antics, and the warped, wavy contours of his Guild S-200 Thunderbird. Like Zal himself, it was a guitar ahead of its time, complete with a “kickstand” built into the back body. If you were serious about rock guitar in the mid-Sixties, Yanovsky is a guitarist you were serious about.

He was an early adopter of the Thunderbird, and the broad range of tonal colors he could achieve with that guitar inspired Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen to get his own Thunderbird, which he played on the landmark psychedelic tracks White Rabbit and Somebody to Love, from Jefferson Airplane's 1967 album, Surrealistic Pillow.

“[Zal] was a great player, so of course I checked out his gear,” Kaukonen later recalled. “The T-Bird was one of the most different-looking guitars I had ever seen… I also bought a Standel Super Imperial [amp] because Zal was playing through one.”

The Lovin’ Spoonful are a major crossroads band in the story of Sixties rock guitar. It was John Sebastian who turned Mike Bloomfield on to the Gibson Les Paul, setting it on the path to becoming one of the ultimate rock guitars. Sebastian’s own 1957 Les Paul ended up in the hands of George Harrison, who named the instrument “Lucy.”

Harrison had received the guitar from Eric Clapton, who’d got it from Rick Derringer, who’d obtained it from Sebastian himself, in a swap for an amp that reportedly took place when the Lovin’ Spoonful were on the road with Derringer’s hit-making garage rock band, the McCoys. The Spoonful guitar lineage is almost Biblical in magnitude.

As is their importance in the music we now call Americana. Back then, we just called it folk-rock. Along with the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and Simon & Garfunkel, the Lovin’ Spoonful were one of the key groups to emerge as part of the folk-rock scene that Bob Dylan had ignited in 1965 by bringing electric instrumentation into his previously all-acoustic music.

Electrifying folk traditions opened up new stylistic vistas in rock music and rock guitar playing. Accomplished folk pickers like Jerry Garcia, Roger McGuinn, Stephen Stills, Jorma Kaukonen and others began ditching their Martins for Strats, 335s, Rickenbacker 12s, and, yes, even the odd Guild Thunderbird.

Yanovsky had come up as part of that wave. Born in Toronto, he was among the folk-rooted Canadians – Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen and Robbie Robertson among them – who’d migrated down to New York’s Greenwich Village and its legendary folk scene in the mid-Sixties.

The Village had launched Dylan, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul & Mary, and others into the pop mainstream. Folkies flocked there hoping to be next in line. There were more skilled folk pickers per square foot of Greenwich Village real estate – which, unbelievably, was relatively cheap back then – than had probably ever been amassed in any previous time or place.

By the time Yanovsky landed in the Village, he’d teamed up with fellow Canadian, and future Mamas & Papas singer, Denny Doherty to form the Halifax Three. In New York, Yanovsky and Doherty joined forces with Cass Elliot, another future Mamas & Papas singer, to form the Mugwumps – a group that has been described as Greenwich Village’s first rock band.

“Zally” brought a dazzling range of styles to the picture, based on his deep listening to American vernacular music. Charlie Christian’s guitar work on One Sweet Letter from You with Lionel Hampton was one of the tracks that entranced him as a teenage guitar novice. But he was drawn to a broad range of players and styles.

I was never a big Elvis fan, but I liked Hank Williams, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Ray Charles, Fats Domino, and Huey ‘Piano’ Smith

Zal Yanovsky

“I liked Elmore James, Chet Atkins, Floyd Cramer,” Yanovsky told one interviewer. “The first time I heard [Buddy Holly’s] That’ll Be the Day, it was a killer. I liked Ferlin Husky’s Gone. Hank Ballard’s Finger Poppin’ Time blew me away. I was never a big Elvis fan, but I liked Hank Williams, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Ray Charles, Fats Domino and Huey ‘Piano’ Smith.”

Yanovsky’s wide vocabulary as a guitarist is what led aspiring singer/songwriter John Sebastian to poach him from the Mugwumps, enticing him to join a new band that Sebastian and his manager were putting together in late 1964.

“He could play like all these [different] people, yet he still had his own overpowering personality,” Sebastian later recalled. “Out of this we could, I thought, craft something with real flexibility.”

Sebastian brought his own impressive range of stylistic influences from early 20th-century blues, jug band, string band, ragtime and kindred styles. Like a lot of ambitious songwriters, he aspired not only to write hit songs but to write in a variety of styles that are considered great songwriters’ genres – mournful country ballads, Tin Pan Alley standards, raunchy blues, risqué rags…

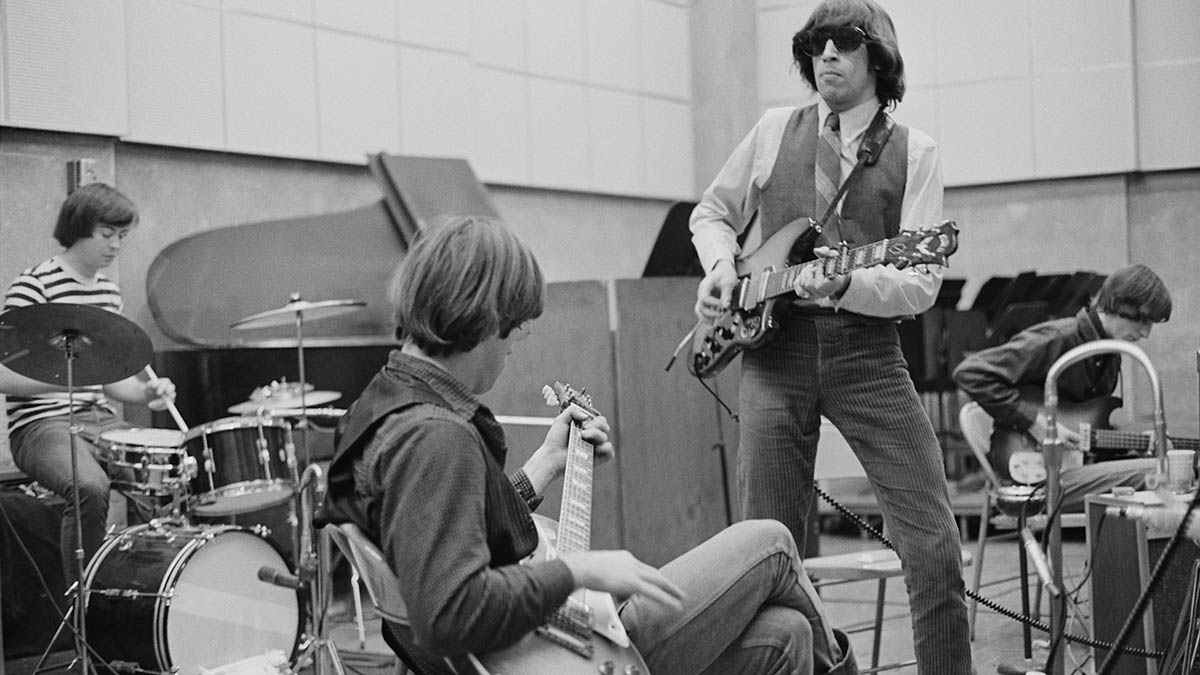

Yanovsky had the scope and six-string wherewithal to provide just the right licks and tricks to serve this agenda. And when the rhythm section of Steve Boone (bass) and Joe Butler (drums) fell into place, the Lovin’ Spoonful were born. The group name came from a line in Coffee Blues by Mississippi John Hurt, a bluesman whom Dylan also admired and emulated.

The Lovin’ Spoonful often described their sound as jug band music – a nod to the African-American folk genre that flourished in Memphis in the 1920s-’30s with groups like Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers and the Memphis Jug Band. Of course, the Lovin’ Spoonful weren’t an actual latter-day jug band like, say, Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band. Nobody ever blew across the top of a whiskey jug to create bass notes.

But the tag was indicative of the Spoonful’s old-timey vibe. This was something that had become trendy in the mid-Sixties, via pop hits like Winchester Cathedral (1966) by the New Vaudeville Band and Hello Hello (1967) by Sopwith Camel, perhaps finding its ultimate expression in the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s period.

Most of all, the jug band label helped differentiate the Lovin’ Spoonful from other artists lumped under the folk-rock tag. While kindred spirits, they were all quite different. The Byrds didn’t sound like the Buffalo Springfield, who didn’t sound like Bob Dylan. If anything, the Lovin’ Spoonful wore their folk influences more prominently on their sleeves than some of the other folk-rockers. They were fairly unabashed, venturing into stylistic realms that might easily have put off teenage rock ’n’ roll fans of the day.

As it turned out, however, the kids loved it. Between 1965 and ’66, the Lovin’ Spoonful landed no fewer than seven tracks in the Top 10. The first of these, Do You Believe in Magic, exemplifies what was always the most prominent influence within Yanovsky’s eclectic rootsy style – Chet Atkins-inspired country picking. Staccato, palm-muted embellishments, gorgeous volume swells, deep-talkin’ low notes – these quintessential country moves were all integral to his guitar vocabulary.

Yanovsky was a trailblazer in bringing country guitar into rock music. A good two years before the Byrds famously “went country” with Sweetheart of the Rodeo, Yanovsky was twanging away on tracks like Nashville Cats from 1966. At times, his guitar work can sound a bit like that of the mid-Sixties’ other great Chet Atkins rock ’n’ roll acolyte, George Harrison.

Yanovsky walked it like he talked it – or played it, in this instance. He’s generally credited as being the first rock musician to sport cowboy hats and fringed buckskin jackets. By the time Woodstock rolled around in ’69, all that buckskin fringe had become a counterculture commonplace, if not cliche; but in ’65 it was fresh and new. That’s how quickly the zeitgeist moved in those days.

Western wear was just one element in Yanovsky's wonderfully off-kilter fashion sense, which also embraced things like mile-wide mod neckties, slept-in looking corduroy jackets with buttonhole flowers, vests, and, of course, the ubiquitous striped T-shirts that Brian Jones had brought into vogue.

Yanovsky also slotted into a mid- to late-Sixties phenomenon that might be described as 'counterculture Jewish cool'. Other key exponents would include Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Mike Bloomfield, Lenny Bruce, Abbie Hoffman, Leonard Cohen and Woody Allen.

But Yanovsky’s yearning, playful, wildly inventive guitar style is what set him apart. It’s interesting that he cited country piano legend Floyd Cramer as one of his guitar influences. Both men could break your heart just by rolling the second interval up to a major third at just the right moment in a song.

The sparkling lead guitar on Lovin’ Spoonful hits, moreover, was just the tip of the iceberg, enticing savvy listeners to deep album tracks that took matters further afield. The mid-Sixties were the time when the 33 rpm vinyl album began to eclipse the 45 rpm single as rock music’s main expressive medium.

The songs that bracketed the big hits on an LP were no longer mere low-quality 'filler'. Groups began exploring this extra vinyl real estate to create music that might not be commercial enough for the mainstream, but was still interesting to their more serious fans.

In the Lovin’ Spoonful’s case, this meant a deeper dive into folk tradition, which in turn provided Yanovsky with a spacious canvas. On the group’s debut album, Do You Believe in Magic, he serves up some countryish playing on Blues in the Bottle, and his supple electric fingerpicking energizes Fishin’ Blues. The latter is a song from 1911 by country bluesman Henry Thomas, misattributed to Sebastian on the album sleeve.

Sebastian would later reference Henry Thomas in a song by that name on the Spoonful’s third album. And in a era when the 12-bar urban blues idiom was rapidly becoming an almost obligatory showcase for rock guitarists, Yanovsky provides some first-rate, reverb-y, late-night comping and soloing on the standard Sportin’ Life and the instrumental Night Owl Blues, a nod to the Greenwich Village club where the Lovin’ Spoonful honed their act in 1965.

“The first album is a good reflection of our shows,” Yanovsky later said. “It wasn’t like we had a mission statement or anything, so we played what we liked… I was 19. It was great.”

With a few hit records to their credit, the Lovin’ Spoonful were able to stretch further and dig deeper on their second album, Daydream. It was named for their old-timey 1966 hit, which featured more fine Chet Atkins-inspired lead guitar work from Yanovsky.

The LP is less reliant on folk traditional repertoire than the first disc. There are more songwriting contributions from Sebastian, both on his own and in collaboration with bandmates. He and Yanovsky co-wrote the wistful It’s Not Time Now, which features some supple electric fingerpicking from Zal.

Daydream is also where Yanovsky began to expand the range of tones he was able, and often perversely willing, to wrest from the electric guitar. He was the kind of guy who wasn’t afraid to go full fuzz on a country number like There She Is.

This is the wonderful thing about the Lovin’ Spoonful: they were steeped in tradition, but they were never traditionalists. Their take on America’s folk legacy was lighthearted, easygoing, a bit tongue-in-cheek and never hesitant to reach for an unusual instrument or bizarre tone.

A major example of this on Daydream is Jug Band Music, on which Yanovsky is credited with playing “yackety-throw-up guitar.” This was simply a bass guitar processed through a fuzz pedal – quite a wild sound in ’65, when the album was recorded, and the same year in which the Beatles had their own fuzz bass epiphany with Think for Yourself, from Rubber Soul.

Jug Band Music also features some fine “garage country” guitar interplay between Yanovsky and Sebastian. They were a good two-guitar team, but on many tracks, Sebastian played autoharp, harmonica, or keyboards instead, leaving the guitar work entirely in Yanovsky's capable hands. The goal was always to make each song different – stylistically, tonally or otherwise – never succumbing to formula and always avoiding being pigeon-holed.

Hums of the Lovin’ Spoonful, the group’s third album, would prove to be their crowning glory – their Rubber Soul, as it were, encompassing everything from stately baroque chamber pop to bumptious bluegrass. Among the record’s three Top 10 hits – Summer in the City, Rain on the Roof and Nashville Cats – the latter is surely one of Zal Yanovsky’s shining moments.

The eloquent, chicken-fried licks he weaves around Sebastian’s lyrics and vocal melody are almost like a second, contrapuntal, singing voice – imparting authenticity to the narrative, which misidentifies Nashville, rather than Memphis, as the home of the legendary Sun Records label. And Yanovsky’s brief outro solo leaves you longing for more.

Hums tracks like Darlin’ Companion satisfy that longing with some beautiful two-guitar work from Yanovsky and Sebastian. The track became a country standard after Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash recorded it in 1969. Yanovsky channels Howlin’ Wolf with a fuzzy riff and “wolf call” vocal on Voodoo in My Basement.

I liked the music, but I didn’t like the business

Zal Yanovsky

He contributes moody guitar atmospheres and jazzy, double-stop octave soloing on Coconut Grove, which he co-wrote with Sebastian. 4 Eyes benefits from tour-de-force slide guitar work that manages to be manic and masterfully nuanced at the same time. And the trippy interludes in Full Measure anticipate the psychedelic revolution just getting ignited at the time.

As if all this weren’t enough, Yanovsky picked up a banjo for the bluegrassy Henry Thomas and bluesy Bes’ Friends, a song that wouldn’t have been out of place in Bessie Smith’s repertoire and which also features clarinet licks played by legendary rock photographer Henry Diltz.

Confirming the Lovin’ Spoonful’s status as a mid-Sixties buzz band, they were chosen to create the soundtrack for the 1966 feature films by two of America’s greatest directors – Woody Allen’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily? and Francis Ford Coppola’s You’re a Big Boy Now.

But by 1967, Yanovsky had left the Lovin’ Spoonful under something of a cloud. For one, an artistic rift had developed between him and Sebastian. The guitarist had little use for the more introspective style of songwriting Sebastian was starting to explore.

“I told John his songwriting had really gone down the toilet,” Yanovsky later recalled. Not long after that, he was out of the band. He appeared on only one track, Six O’Clock, from the Lovin’ Spoonful’s fourth album, 1967’s Everything Playing.

But that wasn’t all. In 1966, Yanovsky and bassist Steve Boone had been arrested in San Francisco for possession of cannabis. In an effort to avoid deportation back to Canada, Yanovsky went along with a police deal to provide the name of the person who’d sold him the weed.

The plan was that the band would hire a high-powered lawyer to defend the dealer in court. But he went to jail nonetheless, and Yanovsky was virulently denounced in the pages of the Los Angeles Free Press and other counterculture outlets.

In the late Sixties, you did not narc on your friends, nor betray your brothers and sisters to 'the Man'. The counterculture had its own cancel culture, half a century before that term came into use.

It dealt a death blow to Yanovsky’s music career. The title of his 1968 solo album, Alive and Well in Argentina, seems to comment on his status as a pariah and exile from hippie utopia.

The album, and his ’68 solo single, As Long As You’re Here, both sank like a stone. Yanovsky played briefly in Kris Kristofferson’s band, appearing with them at the historic Isle of Wight Festival in 1970. But soon after that, he was out of the music game. “I liked the music, but I didn’t like the business,” he later said.

Zal Yanovsky’s departure from the Lovin’ Spoonful also marked the band’s exit from the Top 10. Without him, they’d never hit the top of the charts again.

It’s true that Erik Jacobsen, who’d produced all of the band’s big hits and other recordings, also left the fold at this time. But without the yin/yang, Lennon/McCartney give-and-take between Sebastian and Yanovsky, the magic wasn’t there to believe in any longer. Yanovsky went on to a second career as a chef and restaurateur and died of a heart attack in 2002, at age 58.

While fondly remembered by rock connoisseurs (the Lovin’ Spoonful were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000), his name is likely to draw only puzzled looks from members of the general public.

Volumes could be written on why Yanovsky and the Lovin’ Spoonful don’t enjoy the same status as other successful and stylistically important Sixties rock groups. A portion of the blame might be placed on Sebastian’s embarrassing, maudlin, stoned and sloppy performance at Woodstock in 1969, which got enshrined in the 1970 movie that everyone has seen a million times.

Sebastian is a phenomenal songwriter and has done much first-rate work over the years, but Woodstock was hardly his finest hour. For many, the tie-died fiasco – in which he failed to remember the words to his own song, the saccharine Younger Generation – became a signifier of the worst kind of self-indulgent hippy-dippy excess. And the Lovin’ Spoonful have tended to be retrospectively tarred with the same brush.

Also, they were a bit too overtly folk to slot into the restrictive Abrams rock radio format of the Seventies – the somewhat circumscribed playlist that went on to forge the current popular notion of “classic rock.”

Folk was a mite too quirky, quaint – and often left-wing – for the Nixon years and beyond. But with the emergence of Americana as a revered genre in recent decades, Yanovsky and the group that brought him to all-too-brief fame are ripe for recontextualization and reconsideration. They are one of the great originators of Americana. It might have happened anyway without Yanovsky, but the ride wouldn’t have been half as much fun.

“Zally had a flamboyant quality so different from the folkie approach to guitar,” Sebastian said in a 2002 interview with Mojo. “He’d be mugging at the audience and crossing his eyes when he played – making it silly and making it funny and taking the wind out of all those blustery guitar players. He’d play the same thing as them, only he’d cross his eyes and stick his tongue out.”