Sometime around the turn of the 8th century, on Lindisfarne, a windswept island off the English coast in Northumbria, a monk by the name of Eadfrith sits down and sharpens his quill. He dips it into the black ink pot before him and, guided by the light of flickering candle, traces the first words of the Gospel of John on to blank parchment.

In principio erat Verbum.

“In the beginning was the Word”.

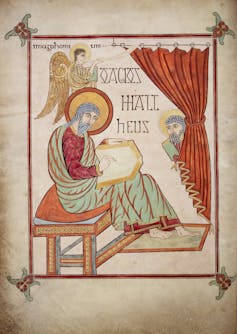

Eadfrith’s task is to copy the Latin text of all four Gospels – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – and illustrate them in what art historians term the insular style, a geometric decorative technique spreading across early medieval Britain and Ireland.

It will take Eadfrith ten years to finish the Lindisfarne Gospels, on view at Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle until December 2 2022, but his masterpiece will be valued for generations. Later owners will add to its pages and the book will be saved from Viking invaders, finding a new home in Durham for 800 years before becoming part of the British Library’s collection via the collector Robert Cotton (1571-1631).

The story of the Lindisfarne Gospels is intimately connected to life in the north east of England. It speaks to the migration of communities, the passing on of artistic traditions and the preservation of a communal history that resonates with modern-day concerns around identity and belonging.

Encrusted with jewels

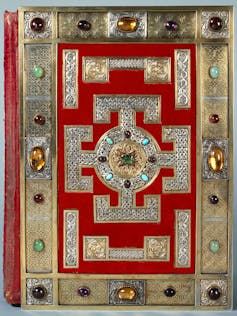

The Lindisfarne Gospels is formed of more than 250 vellum pages and measures just over 36cm in height, about the size of a modern A3 sheet. The book’s original “treasure binding”, encrusted with gold and jewels, was destroyed at some point in the manuscript’s tumultuous history, but the modern copy, commissioned in 1852, and other medieval treasure bindings give some sense of the sumptuous world in which this holy book was created.

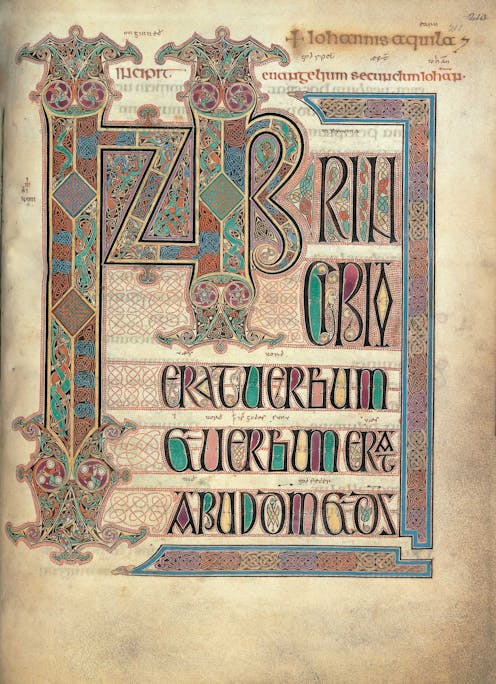

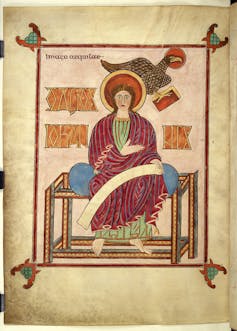

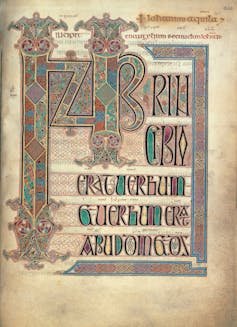

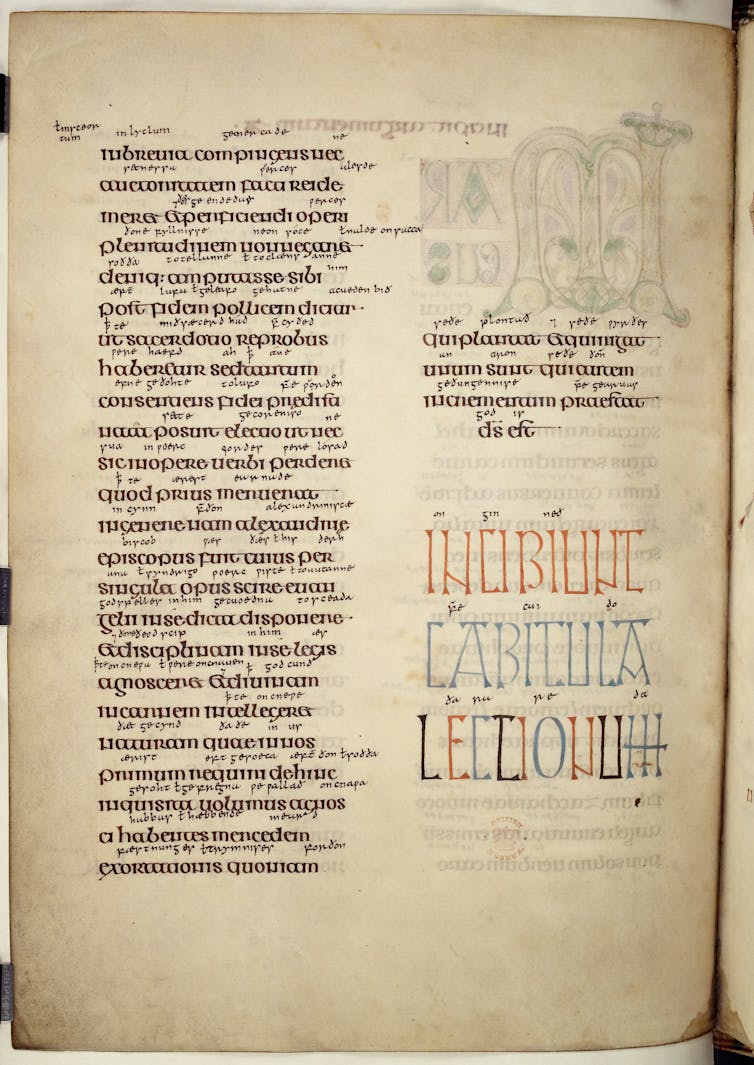

The book opens with letters by the influential Christian theologians and Church Fathers Jerome and Eusebius and with a series of canon tables, organisational systems for comparing stories across the gospels. Then follows the gospel texts, each preceded by an image of its author and an incipit (literally meaning “it begins”) – a page of twisting geometric shapes that form the first words of the text.

The manuscript also includes a Chi-Rho page, where the letters of the abbreviated Greek version of Christ’s name, “XPI”, emerge from a swirling sea of vines. Most impressive of all are its five “carpet” or ornamental pages, where a dizzying pattern of repetitive knots and spirals, designed around the shape of a cross, fill the page.

On closer inspection, the dense mass of painted lines reveals a world teeming with life, from big-footed birds who parade around the borders to long-necked snake-like creatures darting in and out of the twisting shapes. Scholars are still divided as to their meaning, but some of their purpose must lie in their ability to beguile their reader, drawing them into the sacred text.

While these forms recall older worlds on the cusp of Christianity – particularly the Scandinavian-inspired burial goods of Suffolk site Sutton Hoo – they remain rooted in the Christian world in which they were made.

The spread of Christianity

The 5th-century collapse of the Roman Empire splintered Roman Britain into numerous warring kingdoms. By the 7th century, Oswald – son of Æthelfrith of Bernicia – had united Bernicia and Deira under the single banner of Northumbria. Over this powerful land, he encouraged the spread of Christianity.

In 635, Oswald invited an Irish monk named Aidan, from the Hebridean isle of Iona, to be his bishop, gifting him the small tidal island of Lindisfarne on which to establish a monastery. Arriving with Aidan were monks trained to produce the books for which Iona was famed: the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow and the Otho-Corpus Gospels (also on display at the Laing Art Gallery) were all produced on this isle.

The writing room Aidan’s monks established, a scriptorium, paved the way for the creation of the Lindisfarne Gospels a generation later, but its production is linked to another famous event in the island’s history. Cuthbert, Lindisfarne’s prior and later bishop, had already acquired a reputation as a miracle worker by the time of his death in 687. However, when his tomb was opened 11 years later and his body was found to be “incorrupt” (it had not decayed), pilgrims began to flock to Lindisfarne seeking healing. The island became a holy island. (Research has suggested that embalming techniques or the saltiness of the soil might explain why the body was preserved.)

Eadfrith began his work on the gospels in the wake of these events, perhaps designing the book to take centre stage in the elaborate ceremonies performed around Cuthbert’s new shrine. A later inscription in the manuscript records that it was made “for God and St Cuthbert and – generally – for all the saints who are on the island.”

The Gospels survive Viking raids

That the book should have survived for 1,300 years is remarkable. In 793, Viking armies raided Lindisfarne, destroying Cuthbert’s shrine and most of the monastery. The monks fled, taking Cuthbert’s body and as many books as they could carry, including the Lindisfarne Gospels.

After seven years the community settled at the priory in Chester-le-Street, near Durham. It is here that the Lindisfarne Gospels received their final but remarkable medieval addition. In the 10th century, when the manuscript had been in the library of Chester-le-Street for nearly 200 years, a monk named Aldred carefully added a translation of the gospel text in Old English above the Latin.

Aldred’s “interlinear gloss” (so-called because of its placement between the lines of text) is written in Northumbrian dialect in a smaller and spikier hand than Ealdred’s rounded Latin forms. It is unclear why Aldred decided to embark on this ambitious task. The timing, however, corresponds with growing efforts to cement Cuthbert’s cult in Durham and to translate books that had once been closely associated with his shrine in Lindisfarne for those with little or no Latin.

Aldred may also have had more personal reasons for his translation project. One of his inscriptions records that he is translating the text “for God and St Cuthbert, so that he [Aldred] may have admission into heaven; on earth, happiness, peace and success”.

Whatever his motivations, Aldred’s intervention provides us with the oldest surviving version of the Gospels in the English language. As well as a masterpiece of Northumbrian art, the Lindisfarne Gospels is an invaluable record of early medieval history, preserving the words spoken by everyday people in the north of England over nine centuries ago. Its images and text connect us to a world of saints, miracles and Viking invasions, but also a society that cared deeply about its past, its people – and its books.

Sophie Kelly ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.