A family owned, South Otago-based logging company has become the first in NZ to import a hybrid electric-diesel harvester. It’s saved them a pack of money too

Balclutha-based Mike Hurring Logging & Contracting isn’t the biggest forestry company in the country. Neither is it the smallest. But it is the first to introduce what could be a new trend in lower carbon forestry - a hybrid harvester.

Run on a mixture of diesel and electricity, the Finland-made harvester has a battery in the back which charges as the machine moves. Once harvesting, the machine uses electricity from the battery to power the hydraulics that run the feed rollers and saws.

The diesel can kick in when needed, but it’s mostly electric while harvesting.

READ MORE: * Green hydrogen: How Team NZ tech is helping us power ahead * Zombie forests, carbon sinks and the ETS

Mike Hurring is the second of three generations of foresters - his dad logged rimu, and his son Josh works with him in the business. He never really saw himself as an environmentalist, he says, although that’s changed more recently. Instead it was the efficiency of the Logset Hybrid harvester that first drew him to it.

Whereas his other 15 or so diesel harvesters burn 18 or even 20 litres of fuel an hour, the new machine uses only 10.

“I had a heads-up that hybrids were the way to go, and the way fuel prices have risen, I’d love to have a whole fleet of them,” he says. The next harvester Hurring buys will be hybrid, he says, despite the $1 million or so price tag.

The new machine has other sustainability advantages, says Josh. It’s got eight wheels, not the usual six, allowing the machine to go further and cause less ground disturbance.

“It’s a lot less messy.”

High wood recovery rate

Mike Hurring Logging cuts and handles about 250,000 tonnes of wood a year - a mid-sized company, in an industry where production from a major player might be more than two million tonnes.

“These production thinning machines allow us to recover all the wood felled during thinning, compared with thinning to waste manually, where the trees sit on the floor and rot away," says Josh.

“They go through the blocks, pick out the trees, fell them and then cut them into certain log grades. Then the forwarders come through and sort them, and offload them at the skid where they’re sorted again and put onto the truck. So, essentially they go through three lots of quality control before they get to the port or sawmill.”

“If a stem falls on the boom, it scratches the paint. Whereas if a tree comes down and hits someone, it could be very serious.” Josh Hurring, Mike Hurring Logging & Contracting

As a result, wood that would have been left to waste on the ground (and possibly cause environmental problems later on) brings in a financial return.

“We had one customer, a farmer, who was quoted about $10,000-$20,000 [by a different company] to get his block thinned to waste. We went in with our machines and extracted the wood and got a return [for the farmer] of about the same amount.”

The increasing use of machines - hybrid or otherwise - is also a major factor in forestry safety, says Josh.

“If a stem falls on the boom, it scratches the paint. Whereas if a tree comes down and hits someone, it could be very serious.”

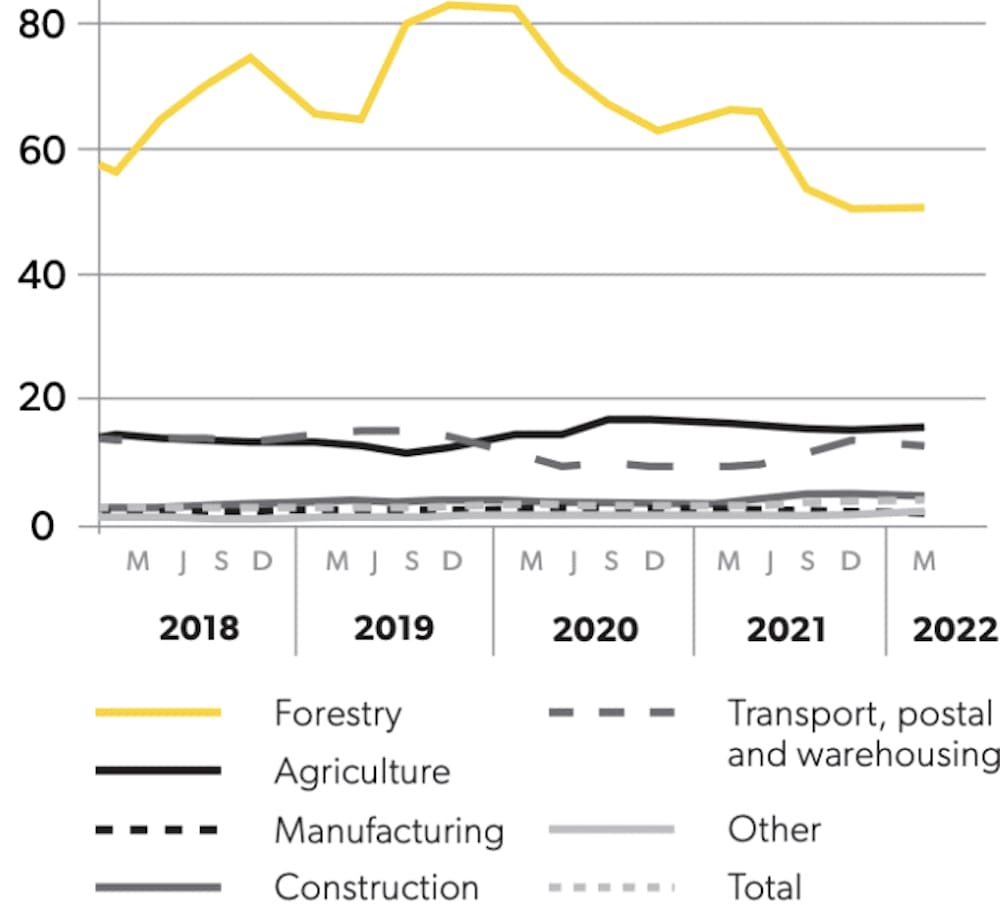

Forestry is a dangerous business. Fatalities per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers on a three-year rolling average is significantly higher in forestry (the yellow line in the graph below) than in other industries, according to the latest Forest Industry Safety Council dashboard (Fisc), though the numbers are coming down.

Industry fatality rate per 100,000 FTEs

Meanwhile, the numbers of injuries needing more than a week off work has risen over the past couple of years on a one-year rolling average basis, according to the safety council numbers.

Fisc/Safetree chief executive Joe Akari says the raw numbers don’t look great, but the rate of serious injury hasn’t risen.

“A lot of those incidents are trips, slips and falls, which can result in lost time, but they aren’t so serious.”

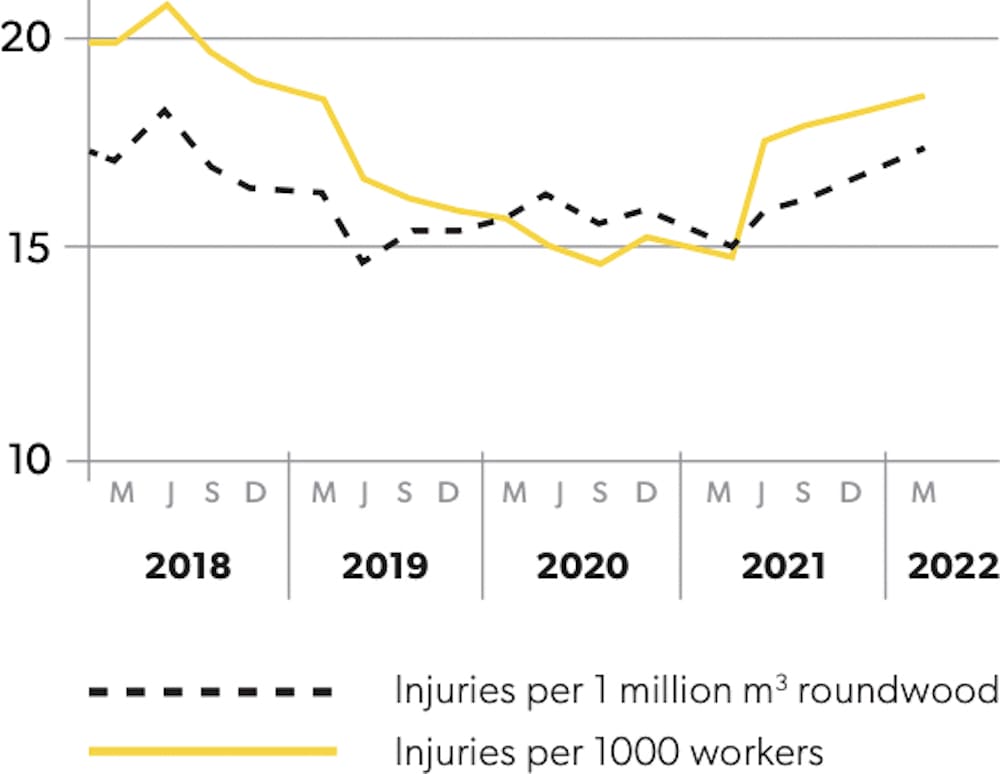

Forestry injury rates

It’s people working manually on the ground cutting trees with chainsaws and hooking logs up to be pulled out of an area where most serious injuries and fatalities occur, Akari says.

“Mechanisation is the most important thing. Higher levels of mechanisation has meant fewer workers on the ground, manually. Instead they are operating in secure environments in cabs.”

Josh Hurring says the new hybrid harvester has other features that help look after the operators. The brakes go on automatically when the doors are opened; and there are exits on both sides of the cab, rather than a safety hatch, making it easier to get out in an emergency. There are also steps that automatically fold down when the machine shuts down

Industry statistics show injuries from falling or jumping off machines are relatively common in forestry.

“All these features add up to make the machines safer for operators,” says Josh.

Hybrid-heads can watch the harvester in action here.