Experts say we have to 'rethink proteins' if we are going to slash agricultural emissions and still feed the world. But what does that mean?

Two seemingly irreconcilable facts hit the Agri-Food-Tech conference last week:

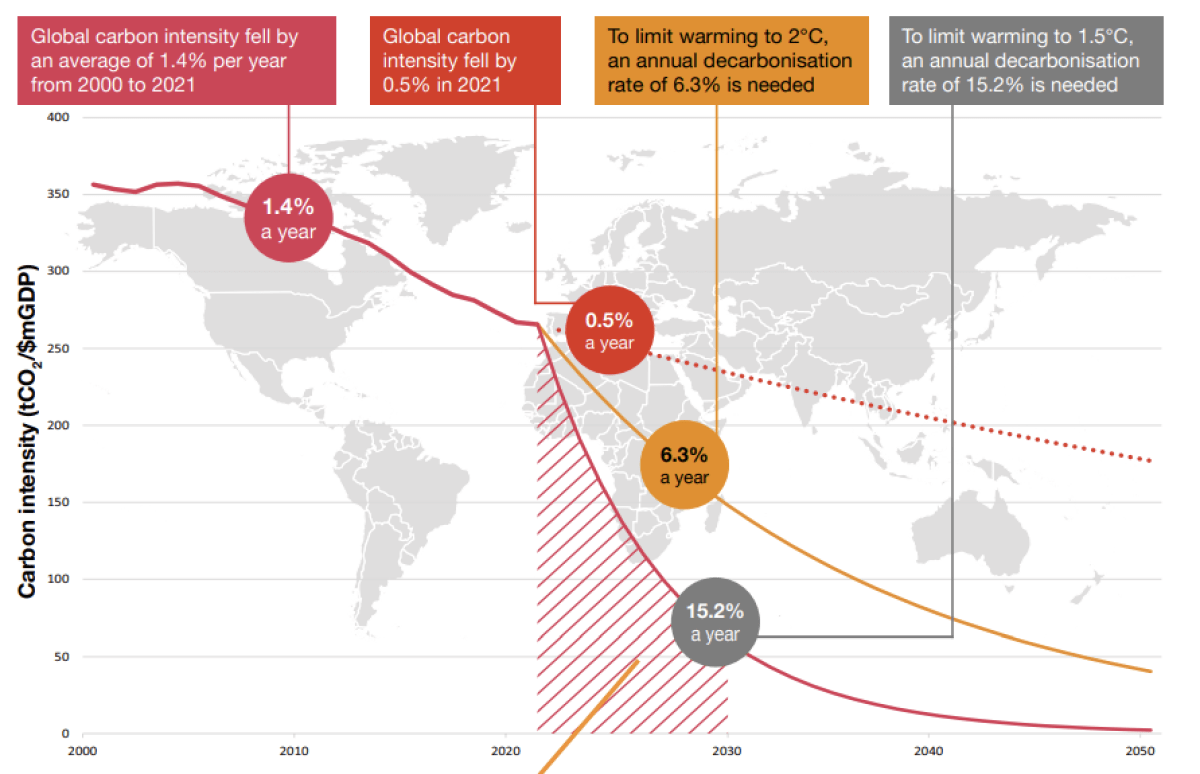

► A 77 percent reduction in carbon intensity is required worldwide this decade to limit global warming to 1.5C, including agriculture.

► We have to feed more than nine billion people

To put these numbers in perspective, carbon intensity - the amount of carbon dioxide produced as a function of GDP - fell by a measly 1.4 percent per year between 2000 and 2021, and an even more measly 0.5 percent last year.

As the graph below shows, to limit warming to 2C we need to decarbonise by 6.3 percent a year, and to get to 1.5C, that figure needs to be 15.2 percent.

Meanwhile, the world’s population will pass eight billion next month and the United Nations’ latest projections put it at 9.7 billion by 2050.

So we are left with the conundrum of trying to feed 25 percent more people but at the same time dramatically decrease greenhouse gas emissions.

“We must rethink proteins,” Aimée Christensen, US-based climate change and sustainable strategy expert and founding executive director of the Sun Valley Centre for Resilience, told the conference in Auckland.

It’s not just that protein is essential to life - it’s also what people want to eat. And the more people move out of poverty into the middle class, the more they want to eat protein.

Trouble is, producing those traditional proteins - meat and dairy - uses a disproportionate amount of the world’s land and resources, and produces a significant amount of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Half the world’s total population is now middle class or wealthier. Hong Kong’s 7.5 million people eat the most meat per capita - more than 400g per person per day, says Nick Hazell, founder of v2, Australia’s largest plant-based meat company.

“What happens when China gets rich?”

What’s the alternative?

Professor Michelle Colgrove studies alternative proteins and is the leader of the Future Protein Mission at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia.

She doesn’t particularly like the word “alternative” when it comes to protein sources; she uses “complementary” when talking about ‘animal’ versus ‘other’. Basically we are going to need all the sources of protein we can get, she says.

“We need to produce more protein more sustainably from more sources to feed the world.”

Fish and seafood are the most accepted alternatives to land-based animal protein, but those industries have their own significant issues around sustainability.

Plant-based meat is another option, but has traditionally been more expensive - and not always had the taste or texture of the animal original.

“We need to produce more protein more sustainably from more sources to feed the world.” Professor Michelle Colgrove, CSIRO

V2’s Nick Hazell says the carbon footprint of his sausages, mince and patties made from legumes, fibre, oil and coconut fat is 40-50 times better than real meat.

“But there’s no way people are going to buy it until it tastes as good and is as cheap.”

There have been some real technical challenges, he says, but reckons he is close to being able to sell his products at the supermarket at the same price as meat.

“It’s no longer just expensive meat for rich vegans.”

Around 10 percent of people in New Zealand and Australia are vegetarian - although not many are vegan, Hazell says. Around 30 percent have been vegetarian or vegan, and 70 percent say they are reducing their meat intake for health or environmental reasons.

Michelle Colgrove says 75 percent of the global food supply comes from 12 plants and five animal species. There’s a big opportunity to expand beyond the traditional sources of alternative protein - soy and wheat - into under-utilised varieties of legumes, pulses, even seaweed products.

Meanwhile, artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to revolutionise the creation of new protein alternatives. In the past, finding the right combination of the 250,000 or so edible plants in the world to make a product with the right taste, texture and nutrient qualities has been a matter of trial and error, or sometimes luck.

Computers, helped by human feedback, can try endless permutations, learning as they go. Even at its early stages, AI has come up with some surprises, Colgrove says.

“JUST Eggs found that the isolated protein of the Indian legume, the mung bean, has very similar properties to scrambled eggs.

“And the Chilean food tech company NotCo used AI to design a plant-based mayonnaise that uses peas, basils, potatoes and canola oil. They are now looking at a chocolate prototype that combines broccoli, goji berries, a champignon mushroom and a nut.”

Beyond plants

Then there’s insects. Experts like Colgrove and Christensen say for the moment, in New Zealand and other first-world-consumer markets, bugs - or extracts from bugs - are more likely to be going into food for pets, farmed fish or chickens, rather than humans.

Your cat might love to catch and crunch flies, but when did you last eat an insect?

Still, farming insects needs less land and less water than farming animals, and insect protein is tipped as an $8 billion market worldwide by 2030.

Then there’s the really clever stuff - precision fermentation, and cultivated/cellular meat. Think growing meat from embryonic stem or muscle cells in a lab - or dairy equivalents in a tank.

There are something like 80 companies around the world researching and raising money in this high-tech space, says Monash University biotechnology professor Michael Wood.

In his neck of the woods, Brisbane-based Nourish Ingredients has pioneered a yeast fermentation process which allows it to produce fats with a similar molecular structure to animal fats - without the animal.

“Fat molecules give proteins the taste and texture that we’ve grown to expect,” the company’s website says. A steak that sizzles on the barbeque, the feel of frozen yogurt on your tongue.

Fellow Australian company Eden Brew is working on creating a sustainable, animal-free, precision-fermented milk.

Meanwhile, lab-grown meat is increasingly scientifically possible, if not yet financially viable.

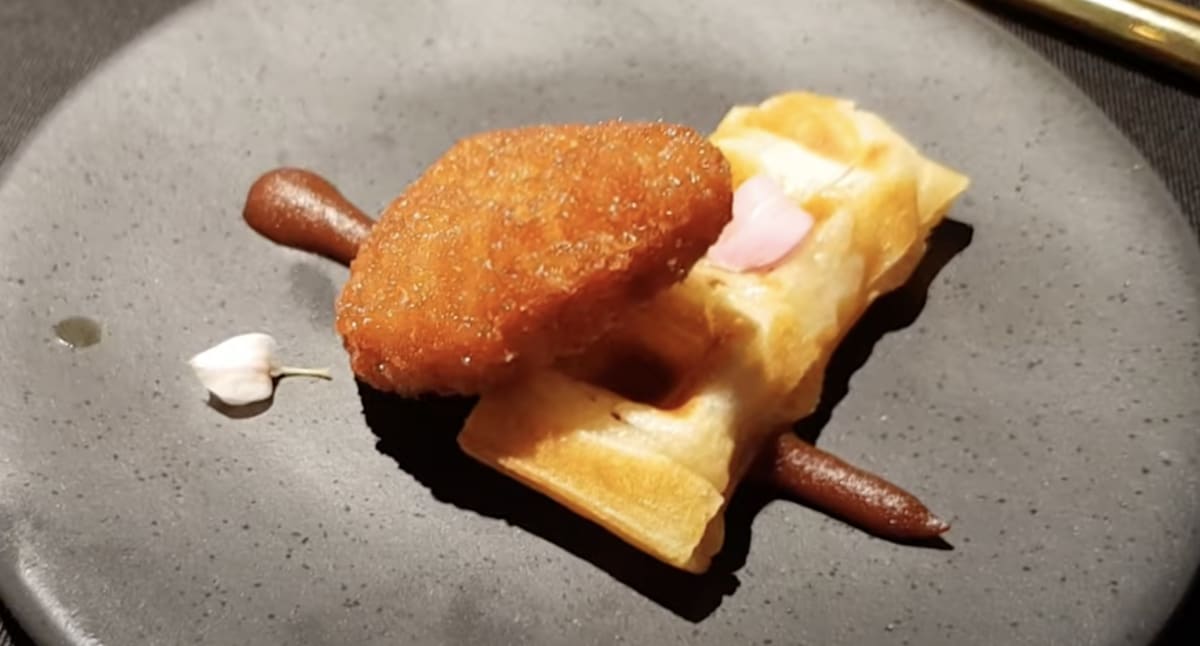

In December 2020, Singapore became the first country to give regulatory approval for a lab-grown meat product - chicken nuggets developed by San Francisco start-up Eat Just and (still) sold in just one exclusive Singapore restaurant.

Eighteen months later, Eat Just subsidiary GOOD Meat has started building a cultivated meat production facility in Singapore, due to open in 2023. Another one is planned in the US.

On the wilder end of the spectrum, Israeli food technology startup Aleph Farms is honing its cell-grown meat technology with a project to allow astronauts to culture their own beef on the International Space Station, 400 kilometres away from earth.

There’s been a lot of talk about lab and fermentation protein replacing real meat. A 2019 report by think tank RethinkX caused a stir with predictions that US beef and dairy production volumes would fall by more than 50 percent by 2030, and by nearly 90 percent by 2035 causing the “collapse” of the livelihoods of farmers.

Michael Wood doesn’t think that’s going to happen - not anytime soon at least. The processes to grow particularly cell-based meat are hugely complex; capital and labour costs to scale the technology are high.

“The high cost of production for this niche market won’t disrupt the meat market.”

He says only 11 percent of Australians drink plant based milk - and the numbers are pretty static. Around 95 percent of families have some sort of dairy in the fridge.

Michelle Colgrove says it isn’t about animal versus plant or cell-grown proteins. We’re going to need everything.

Take milk, for example.

“We don’t need to disrupt the dairy industry. We need more, other products to fill a gap. Traditional protein dairy products will continue to provide the protein we are used to. But as we think about how we produce more and do it more sustainably and how we address growing demand, other products will complement supplies.”

Colgrove’s initial target is to see non-animal protein get to a 10 percent market share - and then grow from there. A 10 percent non-animal protein base is not going to be enough to get a 77 percent reduction in greenhouse gas intensity over the next decade, she says.

“We need all actors to come together. We need policy incentives to encourage that change and we need technology to make sure whatever products we put on our plates are tasty, have the right texture, and price parity, so consumers can make a purchasing decision.

“We have to have incentives from government and we need partnerships between industry and government.”