Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics, always envisioned the Games as much more than the sum of their parts. “Olympism,” as he coined it, was a new type of religion – one shorn of gods, yet transcendent all the same.

To Coubertin, honing an athlete’s body and mind for peak performance in a competition was a way of “realizing perfection.” And if the competition were nation vs. the world, held in varied host cities every four years, individual interest would be subordinated to national pride and a global synergy. Coubertin called this sport in the service of global harmony – nothing short of a new “religio athletae,” or “religion of athletics.”

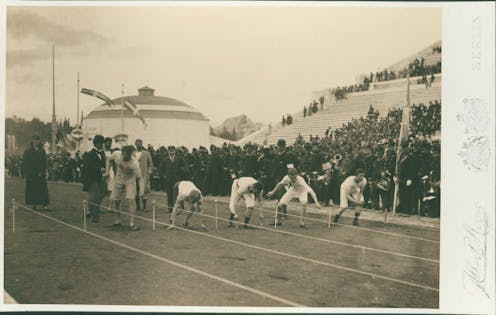

Just two decades after the Games’ modern revival in 1896, Europe was torn apart by World War I, making the dangers of national rivalries all too apparent. And as Coubertin, a French baron and pacifist, wrote, “unbridled competition engenders even an atmosphere of jealousy, envy, vanity and mistrust.”

He was convinced that these baser instincts could be bridled, however, by a “regulator” that was “grandiose and strong.” Expressed through Olympism, the religion of athletics could regulate sports and national pride in a way that produced global harmony at one site every four years – a goal unachievable through politics or sectarian religion.

But the Games have seen no shortage of challenges over the past 100 years. As researchers who study religion and sport, we wonder whether Coubertin’s lofty ideal of the “religio athletae” is still in play – if it ever was.

Ancient inspiration

Coubertin’s desire to resurrect the Olympic Games after 1,500 years of dormancy was prompted by his concerns about challenges and changes in the early 20th century. He believed, for example, that industrialization was rendering young men physically and morally weak.

Meanwhile, with the rising explanatory power of science, traditional religion was relied on less and less as a panacea for the world’s ills. A new world was dawning, and he hoped Olympism would act as a corrective. A rather obsessed aficionado of ancient Greece since childhood, Coubertin saw the ancient Games as containing ingredients that, if modernized, could uniquely respond to some of the big problems of his day.

Specifically, he looked back to the ancient Greek ideal of mind and body in harmony, which competitors expressed every four years in the Greek town of Olympia, the sanctuary for Zeus. The Games were open to Greek men – women and enslaved people could not participate – and matches could be brutally fierce.

By making this ideal the foundation of the modern Games, Coubertin hoped to infuse them with a sense of balance, proportion and reverence. The Olympics would bring enchantment from ancient Greece into the 20th century – symbolized, to this day, by the relay of the torch from Olympia to the opening ceremony.

Not all of his attitudes about the ancient Games were glowing. Coubertin also believed they had been “chaotic,” “impractical and bothersome,” as well as prone to excess and corruption. He worried that the modern Olympics could end up similarly.

At the same time, he had faith that the spirit of the Games could be a “regulator” on the kinds of excessive behavior that sports can invite. At ancient Olympia, Coubertin wrote, “vulgar competition was transformed and in a sense sanctified” out of respect for bodies and minds working toward the perfection represented in the gods.

The Games today

The International Olympic Committee has repeated Coubertin’s desires of forging unity and peace through athleticism. Current IOC President Thomas Bach said, “The shared goal of the U.N. and the IOC is to make the world a better and more peaceful place. For the IOC, this means putting sport at the service of the peaceful development of humanity.”

Indeed, it’s nearly impossible to think of another event, other than sports, that brings together as many countries from all over the world to compete under the same rules without the threat of violence.

Every two years billions of people experience this welling of both national and global pride, as the five interlocking, multicolored Olympic rings are meant to symbolize. And while the Greek gods – or any god, for that matter – are not featured, a kind of civil religion still binds athletes and spectators to the “global congregation” that the Olympics is designed to generate.

What Coubertin could not foresee was the role that money and politics would play – hearkening back to the “vulgar competition” that he believed had undermined the ancient Games. Cities vying to host the Olympics often launch projects that damage the environment and local neighborhoods, and countries have been accused of “sportswashing”: using the feel-good publicity of sports to distract from a deplorable human rights record. For example, the Nazi government famously used the 1936 Olympics in Berlin as a showcase for its racial theory of ethnic German superiority.

In other words, the Olympics have been a vehicle for both unethical behavior and international antagonism – in clear violation of Coubertin’s vision.

Perhaps Olympism was always a pipe dream; perhaps sport never possessed the power to craft and sustain a “religio athletae.” We would argue that the episodic rise of healthy national pride and largely unknown amateur athletes is still something for which to admire the Olympics. Yet it’s unclear how the good of the Games can generate an inspiring new “regulator” that transcends individual performance and national medal counts – or whether it’s even possible.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.